Introduction

Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, has committed to the principle of holding only one major fiscal event per year, unless in the case of an economic shock (HM Treasury, 2024). The 2024 Autumn Budget certainly constituted a major fiscal event: the new government announced substantial tax rises, plans to borrow and spend substantially more, and substantial changes to the fiscal rules. The upcoming event on 26 March is dubbed a ‘Spring Forecast’, at which the Chancellor intends to respond to a new set of forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) with a parliamentary statement (Reeves, 2024). It is not clear whether this means that the Chancellor intends to announce precisely nothing in the way of discretionary policy changes, but it does suggest that we ought not to expect anything major.

The principle of holding only one fiscal event a year has much to commend it. Economically, it is a sensible commitment. But there is a complication. In the Autumn Budget, under the OBR’s forecast, the Chancellor was on track to meet her fiscal rules by what is, in the context of the UK public finances, a very fine margin. In the oft-used parlance, she left herself just £9.9 billion of ‘headroom’ against her promise to run a current budget surplus – i.e. to borrow only for investment – in 2029–30 under the OBR’s central forecast, and £15.7 billion of ‘headroom’ against her promise to have public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL) falling as a share of national income in the same year. When we consider that the government expects to spend more than £1,500 billion in 2029–30, we can see that these are very small numbers indeed. All the same, a target for a current budget surplus is somewhat ambitious: in 28 forecasts since the inception of the OBR and before last autumn, 20 predicted that the current budget would be in surplus five years out. But actually running such a surplus (as opposed to just planning to do so in future) is harder: the UK has only achieved it once in the last 20 years (in 2018–19, and then by only £0.8 billion) and it has not been done in a sustained way since the turn of the century (the current budget was in surplus in each year between 1998–99 and 2001–02).

Given economic developments since the autumn, it is possible – though by no means guaranteed – that the Chancellor will now be missing one or both of these fiscal rules under the OBR’s updated forecasts. This prospect is largely a result of her own earlier decisions. She chose a set of pass–fail fiscal rules, repeatedly declared these to be ‘non-negotiable’, and then set out to meet them by the smallest of margins. This left her promise not to make policy changes in the Spring Forecast completely exposed to global events, but also to run-of-the-mill forecast revisions from the OBR. She could have left herself more headroom, or chosen a different fiscal framework (there was a technocratic path not taken, which we discuss below), but we are where we are.

Given that, if – and we should stress that it is still an if – the OBR’s new forecast does put the Chancellor on track to miss her rules by a modest amount, she will face two broad options.

The first option would be to prioritise policy stability. The Chancellor could reiterate her commitment to fiscal sustainability and her fiscal rules, but break the letter of those rules – despite them only being legislated in January – and delay any corrective fiscal action to the full fiscal event in the autumn. This would recognise that twice-yearly fine-tuning of tax and spending plans brings costs, and that in an uncertain world there is no meaningful economic difference between a forecast for a small current budget surplus in 2029–30 and a forecast for a small current budget deficit in 2029–30.

The second option would be to prioritise the fiscal rules. She could abandon her commitment to holding only one fiscal event per year (at the first time of asking), and announce tax rises or (even) tighter spending plans at the Spring Forecast to achieve a forecast for a current budget surplus in 2029–30. The Chancellor might worry that breaching the letter of her ‘non-negotiable’ rules could send an unwelcome signal and affect financial market participants’ perceptions of this government’s ability or willingness to take difficult fiscal decisions. Delaying decisions to the autumn could also make it harder to adjust public service spending plans (given that multi-year departmental settlements are to be agreed in June) and trigger months of speculation about possible tax rises in the Autumn Budget.

This argument between the two options is not clear cut. The government will need to weigh competing considerations. A lot will depend on the weight placed on policy stability relative to that placed on adherence to the fiscal rules, and perhaps on economic versus political considerations. And it is still possible that this debate is purely academic, and that no fiscal action will be needed to continue to meet the fiscal targets. But if it looks like her rules are going to be breached, it seems more likely than not that she will respond by altering tax or spending plans. In this short report, we consider (at a high level) what has changed since the autumn and what this means for the Spring Forecast and (in more detail) some of the options available to the Chancellor.

Economic and fiscal news since the autumn

The world has changed a great deal since the Budget on 30 October 2024. Donald Trump’s election has, among other things, upended the global trade environment and raised the prospect of much higher defence expenditure by European governments. These developments will have significant and far-reaching consequences for the UK economy and public finances (and much else). But these are unlikely to be fully evident, or to be fully addressed, in the Spring Forecast on 26 March.

We focus here on the key economic and fiscal factors likely to feed directly into the OBR’s forecast. We do not seek to provide a precise estimate of how much ‘headroom’ the Chancellor might have, partly because this feature of the debate is such a tiresome distraction from the UK’s underlying fiscal challenges, but also because it will depend so heavily on subjective judgements from the OBR about the UK’s potential medium-term economic growth rate.

Recent data on the public finances

Data on tax revenues and spending can give clues on the health of the public finances, and the underlying economy, throughout the year. Since the start of the financial year in April 2024, the news has been mixed at best: revenues from Pay-As-You-Earn income tax have been relatively strong, reflecting strong wage growth, but this has been outweighed by weak self-assessment revenues. Overall, revenues are below what would be consistent with the OBR’s October 2024 forecast.

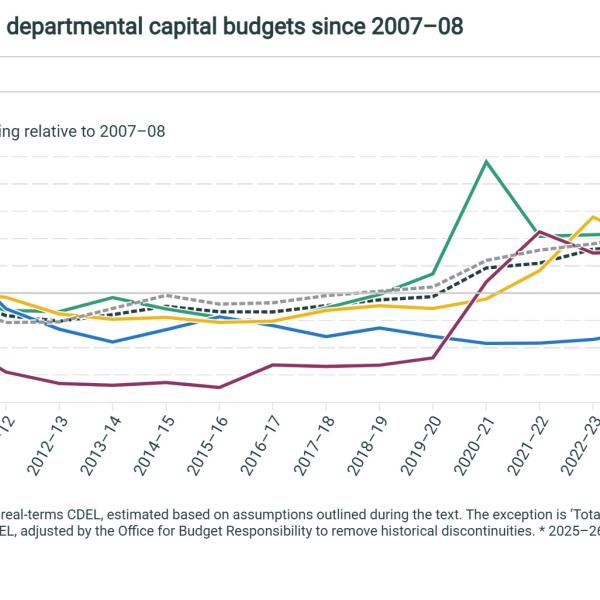

With spending largely in line with the October 2024 forecast, this leaves borrowing above it. A simple extrapolation from the most recent out-turn to the final two months of the financial year suggests borrowing in 2024–25 might be £143 billion, £16 billion above the October 2024 forecast. While most of the focus is on this comparison, we should not lose sight of the fact that this would be £56 billion above the March 2024 forecast. This largely reflects the £50 billion revision to planned spending this year at the October 2024 Budget, including big increases on health, education, defence and the Home Office, as well as the in-year pressures identified at the ‘spending audit’ in July 2024 on areas such as the asylum system and support for Ukraine.

The extrapolated figure would also represent a £12 billion increase on 2023–24 (Figure 1). This figure has itself been revised upwards since earlier out-turns, partly reflecting updated data on local government borrowing. Local government finances are particularly difficult to monitor in real time, meaning that data are more prone to revisions than for other parts of the public sector.

Figure 1. Borrowing: forecasts and out-turns

Note: Public sector net borrowing shown.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook, March and October 2024; Office for National Statistics, Public Sector Finances, UK, January 2025.

These initial out-turns are provisional – in particular, the picture on self-assessment revenues may look less grim once February data (which always contain some stragglers who pay their tax slightly after the end-of-January deadline) are available. In general, relatively large revisions to public finance data are not unusual – since 2015–16, the average revision to borrowing data a year on from the initial out-turn for a given financial year was about 10% of the total amount. We should be wary of drawing sweeping conclusions from these provisional data out-turns. If confirmed however, weak revenues are not encouraging news for a Chancellor hesitant about introducing further tax rises and facing myriad spending pressures.

Growth and productivity

Much will hinge on the OBR’s forecast for economic growth: A smaller economy reduces tax revenues and pushes up borrowing. For the fiscal targets, what will matter is the average rate of growth over the next few years – so, for example, a downgrade to expected growth in 2025 that is made up by stronger growth thereafter could leave the fiscal situation in 2029–30 broadly unchanged. A simple rule of thumb is that a permanent 1% reduction in the size of the economy would push up borrowing by around £11 billion a year in today’s terms. The previous occasion when the OBR revised its productivity growth assumption was in November 2017 when it reduced it by an average of 0.7 percentage points a year, reducing the forecast size of the economy in 2021–22 by 3.0%, adding £25.8 billion to forecast borrowing in that year. So this is an assumption that really matters for the forecast health of the economy, and one that has been changed before.

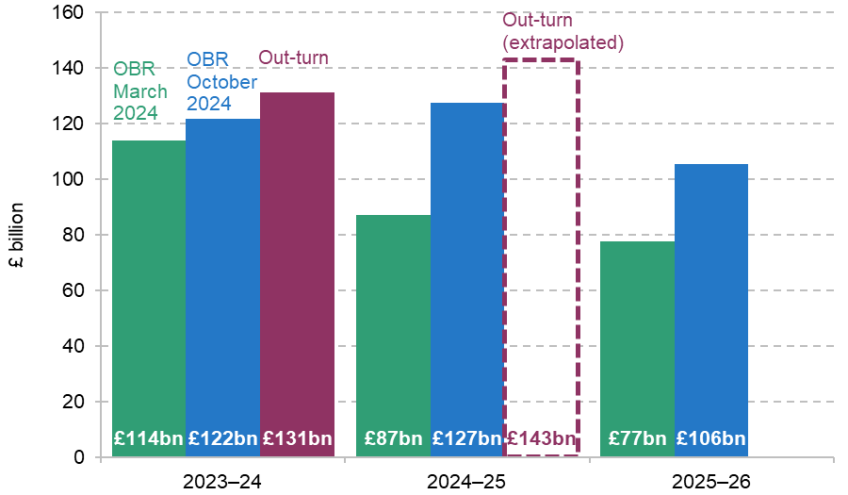

The OBR’s forecast for growth in economic output has long been more optimistic than that of the other key public forecaster (the Bank of England). Other independent forecasters who are regularly surveyed by the Treasury also tend to be more pessimistic than the OBR (Figure 2) although many, especially non-City forecasters, are more optimistic than the Bank of England.

Figure 2. Growth forecasts

Note: Pre-financial average growth between 1949 and 2007.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook, October 2024; HM Treasury’s survey of independent forecasters, February 2025; Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report, February 2025.

The range of forecasts is testament to the enormous amount of uncertainty about future growth and its underlying determinants, including population growth, participation in the labour market, and productivity.

Since the October Budget, new projections from the Office for National Statistics have the UK population grow by more over the coming years, driven by net immigration settling at a higher annual rate of 340,000 people, 25,000 more than in the previous vintage of the projection. There has been some encouraging news on the share of people in work from recent surveys, but low survey response rates remain a huge issue, meaning that there are question marks over the interpretation of these data – even before getting into disagreements about how they may evolve in future. Very recent initial out-turns for growth in output have fallen short of the Budget forecast and are not, in and of themselves, encouraging news. However, the OBR still needs to make a judgement on whether any economic weakness is temporary or permanent: will the economy bounce back and, in five years’ time, be of a similar size to that forecast in autumn, or are these signs of enduringly lower performance?

Inflation and interest rates

Alongside growth in economic output, growth in the cash size of the economy matters for the public finance outlook: taxes are typically levied on cash quantities and spending plans set in cash terms. Therefore, a larger economy in cash terms for the same real output – in other words, higher inflation – can shore up the public finances, even if it is generally unwelcome news for living standards. This is especially true while thresholds right across the tax system are frozen in cash terms. Below, we will return to this mechanism and discuss whether extending threshold freezes could be part of the answer if forecast changes move against the Chancellor.

Since the October 2024 Budget, inflation has outstripped expectations. Consumer price inflation jumped to 3% in January, and domestic inflation (measured by the GDP deflator) outstripped the forecast for the last quarter of 2024. In the first instance, this should have helped to shore up tax revenues. But, as discussed above, the (preliminary) picture on revenues does not look especially rosy.

Inflation also impacts government spending: higher inflation leads to higher spending on debt interest, both directly for the approximately one-quarter of debt that is index-linked, and indirectly as the Bank of England is likely to take a more cautious approach to rate-cutting if inflation looks to be more persistent. In line with this, markets now expect Bank Rate to remain higher for longer compared with the October Budget forecast. This could add some £4 billion to debt interest spending in 2029–30, and this is before any concerns about volatility in debt markets potentially driving up UK gilt rates over and above movements in Bank Rate.

Most working-age benefit spending is, by default, linked to inflation. Higher inflation will therefore lead to higher benefit spending (and preserve benefit claimants’ purchasing power, as the policy intends) into the medium term: a 1% increase in the price level would add £2 billion a year to social security spending and a further £0.5 billion a year to spending on public service pensions. Spending plans for public services, in contrast, are set in cash terms. It is therefore a policy choice to adjust them to accommodate spending pressures from higher inflation – or to ask departments to absorb these pressures within existing cash budgets. We set out some of the options towards the end of the next section.

Summary

The economic and fiscal news since last October has been mixed, bordering on disappointing. That does not mean the fiscal rules will now require further fiscal action to avoid being missed. There are many moving parts to the forecast. But it must make that outcome more likely. In the next section, we go on to discuss the Chancellor’s options in the event the forecast does move against her.

If the forecast deteriorates, what are the Chancellor’s options?

We assume for the purposes of the following subsections that the OBR’s updated economic and fiscal forecast will put the Chancellor on track to miss her rules.

The technocratic path not taken

The Chancellor’s commitment to holding a single fiscal event per year, unless in the case of an economic shock, has much to commend it. But the OBR is legally required to present at least two economic and fiscal forecasts each financial year. This raises the question: what happens at the second (non-fiscal event) forecast if there is no major economic shock but the OBR forecast moves by enough to put the government on track to miss its fiscal rules?

HM Treasury had the foresight to plan for this scenario when designing the new fiscal framework. The key section from the Charter for Budget Responsibility is as follows:

‘the current budget must be in surplus in 2029–30, until 2029–30 becomes the third year of the forecast period. From that point, the current budget must then remain in balance or in surplus from the third year of the rolling forecast period, where balance is defined as a range: in surplus, or in deficit of no more than 0.5% of GDP … this range will support the government’s commitment to a single fiscal event every year by avoiding the need for policy adjustment at forecasts outside of fiscal events. If the range is used between fiscal events, the current budget must return to surplus from the third year at the following fiscal event’

HM Treasury, 2024

The key feature here is that the current budget target (the ‘stability rule’) will apply as a range between fiscal events (i.e. at the Spring Forecast). If the government is missing its rule by a small amount (by no more than 0.5% of GDP), it does not need to respond immediately and can wait until the autumn to take the action necessary to return the forecast current budget balance to surplus.

This is a sensibly designed rule. Crucially, however, this feature is not set to kick in until 2026–27, when 2029–30 becomes the third year of the forecast period. Until that point, the rule states that ‘the current budget must be in surplus in 2029–30’, and this will apply at the Spring Forecasts this year and next. That is, policy adjustment may be needed outside of fiscal events to ensure adherence to the fiscal rules.

The technocratic path not taken would have been to have the fiscal rule apply as a range between fiscal events immediately, rather than only from 2026–27. Alas, the Charter for Budget Responsibility was passed through parliament in January in its original form, meaning that the Chancellor is required to have a forecast for current budget surplus in 2029–30 at the Spring Forecast.

Break the fiscal rule(s) and wait until the autumn

Given that the fiscal rule requires Rachel Reeves to have a forecast for current budget surplus in 2029–30, a forecast for a current budget deficit in that year, however small, would mean breaking the fiscal rule. The Chancellor could, all the same, choose not to act in response to an immaterial forecast change, stick to her commitment to one fiscal event per year, accept that she would be breaking the letter of the rules, and delay any fiscal policy response to the autumn.

In many ways, this would be a rational response. It is daft to fine-tune fiscal policy every time there is a small change in forecasts. Yet it seems unlikely that this would be the chosen path. The Chancellor has been so clear in her commitment to be meeting her fiscal rules that it could be seen as humiliating to be missing them at the first time of asking. It could dent her credibility in the markets. Perhaps weighing most strongly on the Chancellor’s mind would be the fact that to do this would be akin to saying there are likely to be tax rises in the autumn without specifying them. That would lead to months and months of speculation, which would be damaging both economically and politically.

Changes to tax

Following her October 2024 Budget, Rachel Reeves told the Treasury Select Committee that ‘we are not going to be coming back with more tax increases’ (House of Commons, 2024) and repeated a similar message to business leaders later in the year (BBC News, 2024). Yet one option, if she needs to take action to meet her fiscal rules, would be to announce additional tax rises at the Spring Forecast.

There are, of course, any number of ways that the government could seek to raise additional tax revenue. Given that the fiscal rule binds in 2029–30, any change would not necessarily need to raise revenue straightaway. One option that would be consistent with Labour’s manifesto commitments would be to extend the cash-terms freezes to various tax thresholds, which are currently set to expire in April 2028 with thresholds set to increase in line with inflation after that point.

Freezing tax thresholds increases revenue because, as prices rise, the value of a threshold falls in real terms. People whose wages increase only in line with inflation will pay tax on a greater fraction of their income, and may move up a marginal tax bracket. Given the Bank of England’s current inflation forecast, extending the freeze in National Insurance and income tax thresholds by two years (to encompass 2028–29 and 2029–30) would likely raise £5.0 billion in 2028–29 and £10.1 billion in 2029–30.1 If inflation continues to exceed the forecast, the freeze would raise more.

For the avoidance of doubt, we are not endorsing this policy option. We discuss it here only as an illustration of the sorts of revenues that could be gained from a tax rise that recent governments have proved willing and able to implement.

Changes to spending plans

Alternatively, the Chancellor could reduce the generosity of her spending plans. At the October Budget, she set out her plans for the overall amount of spending by departments (the ‘spending envelope’). This will then be allocated between departments via the Spending Review process, due to conclude and be published on 11 June.

Day-to-day public service spending (resource departmental expenditure limits, or RDEL) is set to grow by 1.3% per year in real terms between 2025–26 and 2029–30. As it stands, we know little about how that spending will be allocated. The government does have some specific commitments. Labour’s general election manifesto included a promise to set out a path to spending 2.5% of GDP on defence (Labour Party, 2024), and on 25 February the Prime Minister announced that this target would be met from 2027 (Starmer, 2025). The increase in defence spending, from around 2.3% of GDP in 2024 (under the NATO definition) to 2.5% in 2027, was announced alongside a cut to spending on development assistance (i.e. the aid budget) from around 0.5% of gross national income (GNI, which roughly corresponds to GDP) to 0.3% in 2027.

Because these changes (roughly) offset each other and leave overall spending plans unchanged, they are of limited relevance for the Spring Forecast and will be reflected in the plans set out at the June Spending Review. They are no less significant for that. The increase in defence spending marks the turning point in a decades-long downward trend in defence spending. The Prime Minister’s promise, subject to economic and fiscal conditions, to increase defence spending to 3% of GDP in the next parliament is more striking still. The reduction in the aid spending target similarly marks a notable about-turn on Labour’s manifesto commitment to increase development spending to 0.7% of GNI ‘as soon as fiscal circumstances allow’.

But for the Spring Forecast, what matters is the Chancellor’s plans for the overall level of public service spending, rather than its composition. If she needs to take action to meet her fiscal rules, one option would be to reduce the generosity of those plans. Reducing the planned cash level of day-to-day spending in 2029–30 by around £10 billion would, under the October 2024 inflation forecast, reduce the average real-terms growth rate to around 0.9% per year (down from 1.3%). Doing so would set up an even trickier Spending Review, with bigger implied cuts to non-priority departments – especially if defence spending is to continue to rise beyond 2.5% of GDP after 2027–28. Cuts to the planned level of capital spending would not help achieve the government’s target for current budget balance (which allows borrowing for investment), but could be considered if the Chancellor was on track to miss her rule requiring debt (as measured by public sector net financial liabilities) to be falling between 2028–29 and 2029–30.

The government might not need to pare back its cash spending plans, though. If inflation is now expected to be higher, sticking to the same cash-terms spending plans would equate to a less generous real-terms settlement. Banking the additional tax receipts from higher inflation (with higher prices meaning more VAT, higher wages meaning more income tax and National Insurance, and so on) while leaving cash spending plans unchanged would be functionally equivalent to announcing a cash-terms spending cut under an unchanged inflation forecast (this is what happened, for example, at the 2023 Autumn Statement). While the Chancellor might try to pass this off as not being a policy change, it would clearly represent a tightening in planned spending plans. If you are planning lower real spending increases, you have changed your policy and made real-terms cuts in some programmes more likely.

In either case, reducing the generosity of the spending envelope now, before the Spending Review has concluded, would allow the Chancellor to make cuts at the Spring Forecast without spelling out precisely where they will fall – though it would, in all likelihood, mean announcing bigger cuts to unprotected departmental budgets in June. She could follow her predecessors and ‘game’ the rules by promising unspecified cuts in the final year or years of the forecast, after the Spending Review period, but this would stretch credulity and undermine the credibility of her forecasts. The logic here perhaps points to a paring-back of the overall spending envelope before the Spending Review (which would leave the option of topping up later if conditions allow).

Departmental spending accounts for less than half of all government spending. The Chancellor may also seek savings from within what is classified as annually managed expenditure (AME), most notably from within the social security budget. In particular, the government is expected to publish a Green Paper on disability benefit reform ahead of the Spring Forecast, with some news reports suggesting that the government is seeking to make savings of around £5 billion through changes in work requirements and cuts to the generosity of some payments (Smyth, 2025). Such a package – if the costings are signed off by the OBR – would aid the Chancellor with her fiscal arithmetic.

Conclusion

Rachel Reeves will be hoping that she is still on track to meet her fiscal rules under the OBR’s updated forecast. It is possible that she will be. Higher interest rates and a possible growth downgrade will weigh in one direction. A bigger population and stronger wage growth could weigh in the other. If inflation is expected to be higher for longer, a lot depends on whether spending plans are maintained in cash terms or real terms – though the former case would mean more real-terms cuts for some departments come the Spending Review in June. The event on 26 March could turn out to be an extremely low-key occasion after all.

But it is also entirely possible that the forecast will shift from a small current budget surplus in 2029–30 to a small current budget deficit in 2029–30. That would represent a breach of the fiscal rules announced last autumn to much fanfare, only legislated for in January, and repeatedly described as ‘non-negotiable’. In this scenario, what should the Chancellor do?

There is certainly a case to be made that policy ought not to react to an immaterial forecast revision. A certain amount of volatility in fiscal forecasts is unavoidable, but volatility in policy need not follow. The Chancellor could look through the short-term volatility, trust financial markets to do the same, and commit to doing whatever is necessary to meet the fiscal rules in the Budget in the autumn. The fiscal framework will explicitly allow for exactly this approach from 2026–27, when the ‘stability rule’ will apply as a range between fiscal events; in this sense, she would still be adhering to the spirit of her rules while breaking the letter of them.

Yet such an approach would be risky and seems unlikely. Departmental spending plans will be harder to adjust come the autumn, potentially leaving the Chancellor more reliant on vague spending cuts beyond the end of the Spending Review period (which would lack credibility), cuts to non-departmental spending (such as social security benefits, which would bring their own set of challenges) or tax rises (potentially sparking several months of debate about precisely which taxes will go up, and by how much). The Chancellor’s messaging on the sanctity of the fiscal rules has been unambiguous, and some financial market participants may interpret a breach of the fiscal rules – however minor – as a signal of the government’s unwillingness or inability to undertake fiscal consolidation. With all that in mind, the Chancellor may decide that she needs to raise taxes or cut spending at the Spring Forecast. Ultimately, a lot will depend on much weight she places on these risks relative to the benefits of policy stability – and which of her promises and commitments are deemed most breakable.

Finally, stepping back, while there is no such thing as an optimal fiscal framework, it is hard to believe that the UK’s could not be improved. In an uncertain and volatile world, aiming to meet pass–fail fiscal rules with close to zero headroom leaves fiscal policy entirely exposed to global economic developments (or, more accurately, what the OBR judges the impact of those economic developments might be) and puts the Chancellor’s (sensible) promise to make fiscal policy changes only once a year at risk. If there is a material change then policy should of course adjust. But the twice-yearly fine-tuning of policy in response to immaterial forecast revisions is an increasingly costly distraction from the big issues.

References

BBC News, 2024. Reeves tells firms no more tax rises as she defends Budget. 25 November, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c33ek51rx57o.

HM Revenue and Customs, 2025. Direct effects of illustrative tax changes. Direct effects of illustrative tax changes - GOV.UK.

HM Treasury, 2024. Charter for Budget Responsibility Autumn 2024, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/678fbb377bb65baf62c2ada8/Charter_for_Budget_Responsibility_Autumn_2024_Accessible.pdf.

House of Commons, 2024. Treasury Committee - oral evidence: Budget 2024. HC 320, https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/14971/html/.

Labour Party, 2024. Labour’s manifesto: strong foundations. https://labour.org.uk/change/strong-foundations/.

Reeves, R., 2024. Chancellor commissions Spring Forecast on 26 March 2025. Press release, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-commissions-spring-forecast-on-26-march-2025.

Smyth, C., 2025. Work and pensions secretary battles Treasury over £5bn welfare cuts. The Times, 19 February, https://www.thetimes.com/uk/politics/article/treasury-liz-kendall-welfare-cuts-savings-q0nl66rd0.

Starmer, K., 2025. Prime Minister’s Oral Statement to the House of Commons: 25 February 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-ministers-oral-statement-to-the-house-of-commons-25-february-2025.