UPDATE: Since this article was first published there has been a large upward revision in the forecast price cap for the three months beginning 1 January 2023. In light of this revision we now expect that providing support that covers the same proportion of the increase in bills as intended back in May (when the current support package was first put forward) would now cost a further £18 billion (as opposed to the £14 billion estimated above).

Today’s announcement by Ofgem sees the energy price cap rise to 52p/kWh for electricity and to 15p/kWh for gas from 1st October until the next cap comes into effect on New Year’s Day. For a typical household this will mean a total energy bill of £1,080 for the three-month period spanning 1 October and 31 December. This compares to £590 had the current cap remained in place and £377 for the same period last year – a 187% increase.

In May, the government put forward a support package, consisting of direct support, to tackle the rising cost of living. At the time, this support package represented around three quarters of the rise in energy costs expected over the year. With the energy price cap for the coming 3 months now much higher than expected, it will now only cover 47% of the rise in bills. Covering the same proportion of the increase in bills as intended back in May would now cost a further £14 billion.

Both candidates in the Conservative leadership campaign have promised further support for households. Rishi Sunak has promised further direct support of around £5bn and to remove the 5% VAT charge on household energy bills for 12 months from October. Liz Truss has not ruled direct support, but says her “priority” will be tax cuts, specifically a “one-year temporary moratorium on the Green Energy Levy”.

Of the two, Mr Sunak’s plans are simpler. Today’s Ofgem announcement increases the generosity (and cost) of Mr Sunak’s planned cut to VAT, which would save the typical household a total of £51 over the 3-month period spanning 1 October and 31 December (to which the price cap applies), at a cost of £1.4bn in forgone revenue. Mr Sunak has so far not spelled out exactly how his plans for direct support would be distributed, but suggested it could be paid out to “up to 16 million vulnerable people” (which would amount to an average support payment of £313 each over the course of the year).

Ms Truss’ statements have been more ambiguous. While she has claimed that her “moratorium on the green energy levy” would cut £153 from energy bills, much is still unclear about this proposal. Indeed, there is no single “green energy levy”. Rather, there is a patchwork of different policies that increase energy costs for households and businesses. Revenue from these levies subsidises the generation of renewable electricity, funds the installation of home insulation and provides energy bill discounts to vulnerable customers. Other levies apply only to business’s use of electricity.

Taken together, Ofgem has estimated that various levies and obligations on energy companies, as of the summer of 2022, impose an additional cost of £153 per year on the energy bills of a typical household. The fact that this figure tallies with Ms Truss predictions for her moratorium’s effect on bills suggest that these are the levies she is referring to.

However, this figure will overstate the cost of these levies when energy prices are high. This is because the way in which zero-carbon energy generation is subsidised in the UK means that the cost of subsidies to the bill payers falls as electricity prices rise. New zero-carbon electricity generators are now supported via the Contracts-for-Difference (CfD) scheme, which offers generators a guaranteed (“strike”) price for the electricity that they produce. Prior to the current crisis, the market price of electricity has tended to be below the strike price, and so generators receive a subsidy for each unit of electricity they produce. This subsidy is paid for by a levy on electricity suppliers, which it is assumed, is then passed on to customers through their bills.

Soaring energy prices have changed this situation. The market price for (intermittent) electricity has leapt almost fourfold since the start of 2021 from £64 to £253 per MWh, pushing electricity prices well above the strike prices agree with most zero-carbon generators. In these circumstances, zero-carbon generators pay back the difference between the strike price and the price they receive from selling electricity on the open market. The excess revenue from these generators is then distributed across all electricity suppliers and so would be expected to reduce electricity bills. Net quarterly payments to generators participating in the CfD scheme have been negative since the beginning of this year. In the 3 months from October this year, zero-carbon generators are expected to pay back an unprecedented £3bn.

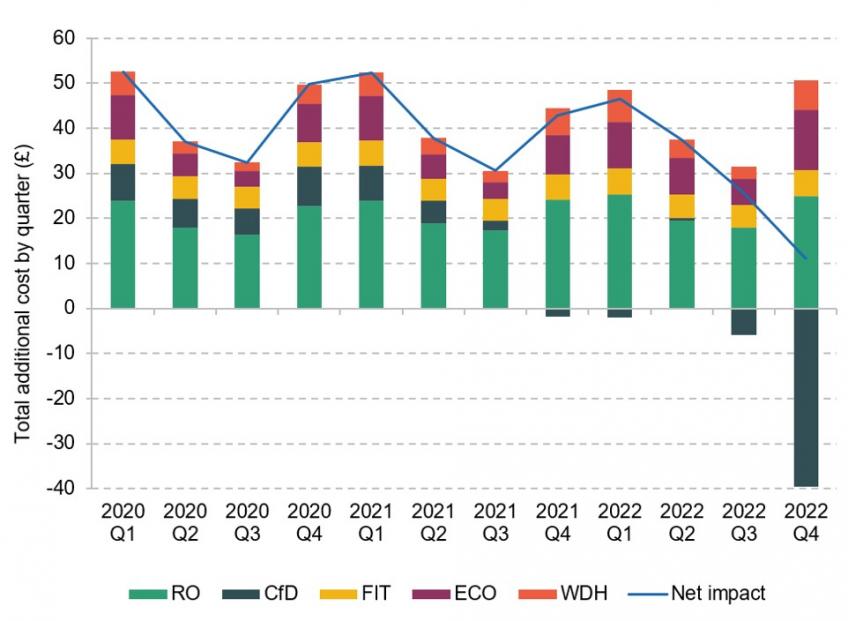

Figure 1 breaks down the cost of the various levies and obligations imposed on electricity and gas suppliers for a typical household bill by quarter (see Table 1 for a description of the individual policies contributing to these costs). It shows that – under the most recent forecast – the downward pressure placed on bills by the CfD scheme is set to wipe out the vast majority of the costs imposed on bill payers from other levies. In fact, taken together, the total net cost of these levies is expected to be just £11 to the typical household’s bill over the three months beginning 1 October – a figure eclipsed by the additional £490 such a household can expect to pay over the next 3 months as a result of today’s price cap rise. This figure will remain low as long as electricity prices remain high relative other prices.

Figure 1. Total cost of ‘green levies’ on bills of a typical household

Note: Levies considered are the Renewables Obligation (RO), Contracts for Difference (CfD), Feed-in-Tariff (FIT), Energy Company Obligation (ECO) and Warm Homes Discount (WHD). Future RO buy-out prices are calculated using RPI as forecast in the March 2022 OBR EFO, while future obligation ratios are imputed from forecast total RO revenue from the same source. CfD costs are derived from actual quarterly CfD payments, divided by total electricity consumption (excluding Northern Ireland and consumption by energy intensive industries) to obtain p/MWh costs. Following Ofgem’s methodology, the aggregate cost of the FIT is obtained by uprating the most recent figures available (for 2020-21) by RPI as forecast in the March 2022 OBR EFO. For the ECO and WHD total policy costs are taken from respective government impact reports and divided by total domestic electricity consumption to obtain p/MWh costs. Following Ofgem’s methodology we assume aggregate ECO and WHD costs to be spread equally between gas and electricity consumers. We follow Ofgem in defining a ‘typical’ household as consuming 2.9MWh of electricity and 12MWh of gas per annum.

Source: Forecast energy consumption from BEIS ‘Energy and emissions projections’ (March 2022), seasonal energy demand profile calculated as a ten-year average of quarterly consumption shares from BEIS `Energy Trends: UK electricity’ (July 2022) and ‘Energy Trends: UK gas’ (July 2022). RO revenue, RPI and CPI forecasts from OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook (March 2022). Past CfD payments from LCCC ‘Actual CfD Generation and avoided GHG emissions’ (August 2022), forecasts for Q3 and Q4 2022 from LCCC ‘In period tracking’ (August 2022). FIT aggregate costs from ‘Feed-in Tariff (FIT): Annual Report 2020-21’. Total costs of ECO from BEIS ‘Final stage Impact Assessment ECO4’ (April 2022). Total costs of WHD from BEIS ‘Warm Home Discount (WHD) - Better target support from 2022 Final stage’ (March 2022).

Although CfDs will tend to have the effect of reducing customers’ bills at high electricity prices, this is not the case for all levies and obligations imposed on energy suppliers. This leaves some scope for reducing bills by reducing or suspending the levies and costs associated with other schemes. For instance, the costs imposed on energy suppliers through the Renewables Obligation, Feed-in-Tariff, Energy Company Obligation and Warm Homes Discount will add around £50 to the energy bill of a typical household over the course of the 3 months starting 1 October. Over the 12 months from 1 October, we expect these costs to increase bills for a typical household by around £180. This is higher than the current estimate from Ofgem mentioned above (corresponding to their value in summer 2022) mainly because of the expansion of the Energy Company Obligation and Warm Home Discount schemes.

Table 1. Summary of current levies on energy suppliers

Renewables Obligation (RO) | The RO provides qualifying green energy generators with certificates for each unit of electricity they produce. Energy suppliers are obligated to buy a fixed number of these certificates for each unit of electricity they sell. Suppliers are expected to pass on the cost of purchasing certificates to the households, businesses and government bodies who buy their electricity. |

Contracts for Difference (CfDs) | CfDs are contracts signed between zero-carbon electricity generators and the government guaranteeing a pre-agreed “strike price” for each unit of electricity sold by the generator. When the market price is below a contracted strike price, the government pays the difference to the zero-carbon generator, funding these payments with a levy on electricity suppliers. If the market price is above the strike price, zero-carbon generators pay the difference back to the government, which then returns it to electricity suppliers. |

Feed-in-Tariff (FIT) | The FIT provides subsidies to small scale generators of green electricity (for example a household that has installed qualifying solar panels). The subsidy is paid for by a levy on electricity suppliers. |

Energy Company Obligation (ECO) | The ECO requires electricity and gas suppliers to provide eligible households with energy efficiency improvements to their homes. The government expects the cost of these improvements to be handed on through higher domestic energy bills. |

Warm Homes Discount (WHD) | The WHD imposes an obligation on energy suppliers to provide discounts to the winter energy bills of certain low-income and vulnerable customers. The cost of these discounts is expected to be passed onto all households through higher gas and electricity prices |

Imposing a “moratorium” on these levies that add to bills is of course possible, but raises a number of awkward questions, the most pressing of which is, what would happen to subsidies these levies fund? One course of action would be for the government to fund these schemes and subsidies temporarily through general taxation rather than through levies or obligations on energy suppliers. This would hold down bills but would also imply substantial costs for the government. Another option would be to cease payment of the subsidies entirely, comes with risks.

As Table 1 shows, levies on energy suppliers fall into two categories – subsidies for green electricity generation and schemes that support certain households with discounts on bills and through energy efficiency programmes. Subsidies for zero carbon energy are supposed to reduce the risk in investing in these technologies by providing generators with guarantees of long-run support. Ceasing payment of these subsidies would not only undermine investor confidence but also risk legal challenges.

For those levies that effectively transfer resources from less vulnerable to more vulnerable bill payers (the ECO and the WHD in Table 1) imposing a moratorium on subsidies would reduce support for insulation programmes and energy bill discounts for poorer consumers at a critical time.

A further question is what the moratorium would imply for businesses, who not only pay the cost of renewable support through levies on electricity suppliers but also additional charges on their electricity use through the climate change levy. Extending the moratorium to cover non-domestic energy use would substantially raise the cost given that households account for less than 40% of total electricity consumption.

Answers to these sorts of questions – as well as to the important question of how much additional direct support to provide to households – will be needed very soon.