Universal Credit (UC) has been steadily rolled out since 2013, with 4 million families now claiming it, but several million still on the older ‘legacy’ benefits that it is replacing. The Budget saw the Chancellor make some tweaks to the system which will (when UC is fully rolled out) increase annual spending by about £3 billion.

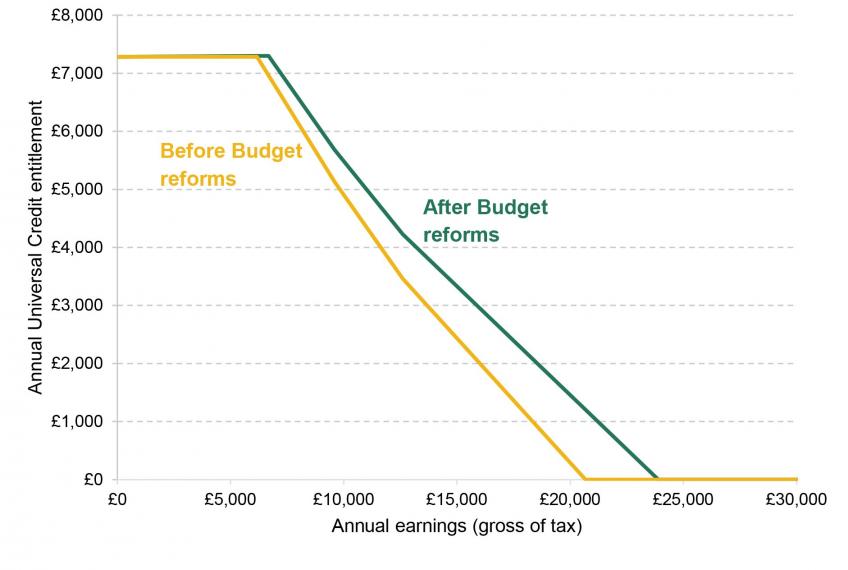

The fundamental structure of the benefit is relatively simple: a basic entitlement is calculated, based on a number of factors such as whether the claimant is a single or couple, how many children they have, how much rent they are liable for (if any), and whether they have any disabilities. That basic entitlement is the amount that they get if the claimant’s family has no other source of income2. Some claimants (those with children or disabilities) are entitled to a ‘work allowance’ – an amount they can earn without losing any UC. As they increase their (total family) earnings above the work allowance they see their UC steadily tapered away. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows annual UC entitlements for an example family (a lone parent, with one child, who owns her own home) both before and after the Budget changes. Prior to the Budget, an extra £1 of (after-tax) earnings reduced UC entitlements by 63p. The Budget reduced that to 55p, and raised work allowances (for those already with one) by £500 per year.

There are two things to note from the figure. First, the Budget reforms increase incomes by significant amounts for those in work; if this example lone parent homeowner worked full-time at the National Living Wage, her UC entitlement would go up by £940 per year. Among all working families entitled to UC, the average increase in income from the reform is £1,100. Second, the reforms also mean that UC stretches further up the income distribution. Before the Budget, a lone parent in this situation could earn up to £20,700 per year before losing all entitlement to UC. After the Budget reforms that figure will rise to £23,900.

Figure 1. Universal Credit entitlements for a lone parent homeowner with one child

Notes: Assumes the child was born before April 2017 so the family receive the higher child element, and that the lone parent does not use paid childcare.

Source: Authors’ calculations using TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model.

UC entitlement extends to even higher levels of earnings for families in other situations. A lone parent with two children and monthly rent of £750 can now earn up to £51,900 before losing all UC entitlement (£44,500 prior to Budget)3. A one earner couple in otherwise the same situation can earn up to £58,900 (£49,300 prior to Budget). It is worth emphasising that this means that a worker, at least so long as they are not a member of a two-earner couple, can easily earn well above the average – indeed, even be a higher rate taxpayer – and still receive some UC (though of course this should not be seen as representative of the average UC recipient)4.

Perhaps not surprisingly given these figures, this means that UC, when fully rolled out, will be received by a very significant fraction of the population. In fact, before the Budget reforms we were on course for 6.4 million working-age families – 24% of the total and containing 14.3 million people (including children) – to be entitled to it at any one time. The Budget changes mean that an extra 600,000 or so families, all in work, will become entitled to some UC, bringing the total to 7 million, or 26% of working-age families, containing 15.8 million people (though, as with all benefits, some will be entitled but not claim; throughout we examine entitlement rather than actual claiming which is considerably more uncertain)5.

But this overall figure masks huge differences by family type. Table 1 shows the number of families entitled to UC after Budget reforms, and what share of each family type are entitled. UC receipt is fairly rare among couples without children; many of those who are entitled have a member with a disability. Rates are higher among couples with children and singles without: one in three of the former group, and one in four of the latter, will be entitled following these reforms. But lone parents are by far the stand-out group – five in every six lone parent families will be entitled to UC. Among lone parent renters the figure rises to 95%. This is both because of their high basic entitlement (in virtue of being a renter and having children) and the fact that many have low or no earnings. Among all families with children, 43% will be entitled.

Table 1. Number of UC families entitled to UC, after Budget reforms

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Family Resources Survey 2019–20 and TAXBEN, the IFS tax and benefit microsimulation model.

The figures discussed so far relate to UC entitlement at a given point in time. Over the course of one’s life, it is likely that most people will at some point be in a household entitled to UC. The UC system thus has implications for many more people than is perhaps widely appreciated. The Budget extends that reach further still.

Notes:

1 Throughout this observation we use the term ‘families’ in the way the government does when determining benefit entitlements: a family is comprised of an individual, any partner, and any dependent children. This means that a single person without children is defined as a family. There can also be multiple families in the same household, such as friends living together or an adult child living with their parents.

2 Technically this is not true for all families: those with significant savings, or subject to the benefit cap, can get less.

3 The maximum support a private renter can get for rent in UC is dependent upon where in the country the claimant lives, and their family composition. A lone parent family with two children of opposite genders, at least one of whom is over the age of 10 are entitled to the “three bedroom rate”. The average three bedroom rate across the whole country is roughly £750 per month. We assume here that the family are able to get £750 per month support for rent. We also assume that at least one child was born before April 2017 so the family receive the higher child element, and that the lone parent does not use paid childcare.

4 The UC system takes account of a family’s total (after-tax) earnings when calculating entitlement, so two-earner families are considerably less likely to be entitled to any UC than one earner families.

5 These figures are for families where all adults are below State Pension Age. A small number of couples where one adult is above State Pension Age and the other below will also be entitled to UC.