The UK’s economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has so far proven rapid but incomplete, and remains contorted by sectoral and regional imbalances. Over the winter, we expect a combination of lingering public health concerns, income losses and supply impairments to all drive a further fading of growth momentum. A sustained and complete recovery remains, in our view, far from secure. Much will depend on the labour market. In this chapter, we assess the outlook for the UK economy and the (many) challenges ahead.

A profound economic adjustment now looms. Many of the changes in patterns of household consumption during the pandemic appear increasingly persistent, and many firms now seem to be expecting and preparing for a different economy in the years ahead. Brexit compounds this challenge: early evidence points to the beginning of a period of acute structural change within UK trade.

Inflation is set to increase sharply in the second half of 2021, with annual CPI forecast to peak at 4.6% in April 2022. But accelerating inflation is currently being driven by just a handful of primarily imported goods, with services inflation, in particular, more subdued. The risks of a more persistent domestically driven price surge for now seem contained – but inflation expectations are a concern. On balance, though, our view is that inflationary pressures should abate, and monetary and fiscal policy need, for now, to keep supporting the recovery.

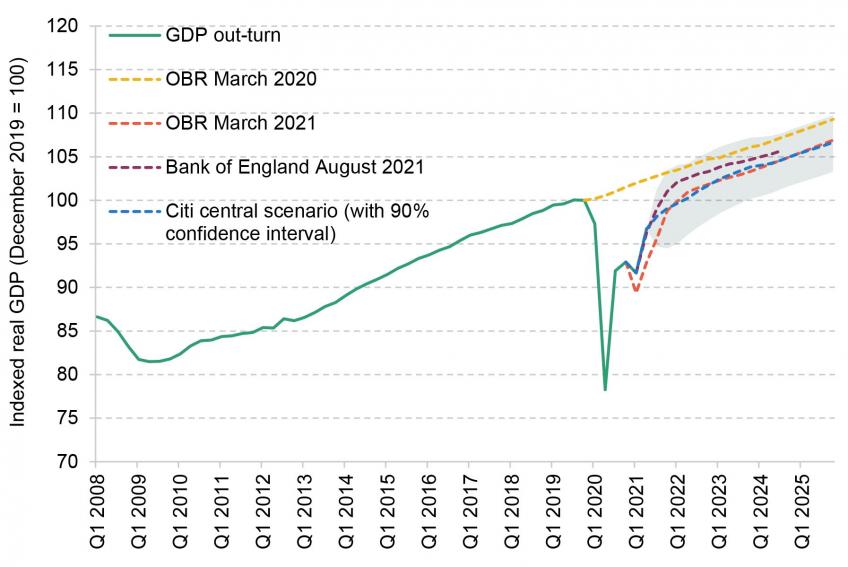

Figure 1. Real gross domestic product (GDP), 2008–25

Notes and sources: see Figure 2.1 of IFS Green Budget 2021.

Key findings

- The UK economy is in the midst of a sharp – but incomplete and wildly imbalanced – recovery. A better public health outlook, easing restrictions and the extension of fiscal support have all underpinned a faster economic reopening in recent months than was anticipated at the start of the year. However, the UK economy still remains one large recession short of its pre-COVID trajectory. The rebound also remains compositionally narrow –and contorted by sectoral and regional imbalances: demand is exceeding supply in some (widely publicised) areas of the economy but lagging it in many others.

- From here, we expect accumulated household savings to provide only a limited boost to growth. As government support is wound down, firms and households will also feel income effects of the shortfall in activity in aggregate for the first time. We expect a combination of lingering public health concerns, income losses and supply impairments all to drive a further fading of growth momentum over the winter. In our view, a sustained and complete economic recovery remains far from secure.

- A profound economic adjustment looms. Economic activity during the pandemic has been characterised by astounding asymmetries. While some of these effects have eased as the economy has reopened, many appear increasingly persistent. Household consumption remains 10% down in social categories, for instance. Firms in transport and storage expect sales to be around 5% higher in the long term as a result of the pandemic, but hospitality firms expect them to be 4% lower. Many firms now seem to be expecting and preparing for a different economy in the years ahead, pointing to a protracted period of reconfiguration.

- Brexit will compound the challenge. Adjustment before 2020 seems to have been put off as a result of continued EU market access and the weakness in Sterling. New-found frictions have added to supply disruption in recent months. Early evidence also now points to the beginning of a period of acute structural change within UK trade. Among goods, we expect the pivot away from EU suppliers and clients to accelerate. Services remain a more notable concern. Professional services exports into the EU have lagged in particular in recent years: exports of professional services to the EU were around 30% of the total in 2021Q1 versus 44% in 2016Q1. We expect these effects to worsen in the years ahead, meaning a likely net drop in overall UK services exports.

- The labour market is the lynchpin of the recovery. While demand has already reconfigured sharply during the pandemic, fiscal support has precluded similar adjustments within the labour market. Sales have shifted across sectors at a much faster rate than has employment, with cumulative excess job reallocation since 2020Q2 24% below the equivalent figure for sales. The result has been an increasingly ‘contorted’ recovery. From here, we expect some of these pressures to begin to unwind. Vacancies should ease back as hiring associated with the economic reopening is completed. Adjustment should now accelerate, with the end of furlough and easing uncertainty facilitating a broader recovery in labour mobility. Our forecasts see unemployment increasing to 5.5% in 2022Q1 as furlough unwinds and more return to the labour force. This may fall back only slowly in the years ahead with matching issues, a capital-intensive recovery and an increase in the effective tax burden on labour from next April all likely to mean the labour market lags rather than leads the recovery.

- Recent wage growth has primarily reflected sector-specific labour shortages, rather than economy-wide wage pressures. Record demand in sectors such as transport and food processing have driven sectoral wage settlements well into the double digits. However, overall pay settlements remain broadly in line with their pre-pandemic range. For now, we continue to think some of these pockets of upward pressure will ease back as supply improves – but a relative revaluation of skills now seems likely. With output forecast to lag the pre-pandemic growth path on a persistent basis, we might expect an emergence of additional labour market slack and lower wages in the years ahead. We expect real household disposable income growth to fall by 0.1% in 2022−23 as living costs increase.

- Inflation is set to increase sharply in the second half of 2021, with annual CPI forecast to peak at 4.6% in April 2022. For now, the drivers here seem transitory. Energy and base effects are likely to push up inflation, as are trade disruptions and imported inflation. These effects could prove sticky, but should ultimately dissipate. The larger risk remains a more persistent domestically driven price surge. For now, the risks here remain more contained. Accelerating inflation is currently being driven by just a handful of primarily imported goods, with services inflation, in particular, more subdued. We also do not expect the labour market to prove sufficiently tight in aggregate to drive up costs on a more persistent basis. Elevated unit labour costs instead seem more likely to drive job losses rather than wage pressures.

- However, inflation expectations are more of a concern. If these begin to shift up, firms may be willing to accept higher wages and offer higher prices – creating the potential for a genuine wage price spiral. Going into the pandemic, inflation expectations were at rather than below target levels – in contrast with both the US and Eurozone. Upwards pressures across firms, households and financial markets are increasingly evident, and acute labour shortages might heighten the risks. However, as transitory inflation likely gives way to disinflation, upside risks in the coming months may also shift to the downside in the medium term. The latter could prove even more difficult to combat.

- With the economy likely to reconfigure over the coming 18 months, the link between the speed and ultimate scale of the recovery is greater than normal. A faster recovery could see COVID-related scarring (i.e. the permanent economic damage done by the pandemic) limited to just 1–1.5% of GDP, versus 3% under the OBR’s March 2021 scenario. A slower recovery could mean larger hysteresis effects and greater permanent losses. Brexit will, in our view, continue to weigh on UK capacity. Combined with our assessment of COVID-19 impacts, this means that we expect the economy to be 2½% smaller in 2024−25 than under the OBR’s pre-pandemic (March 2020) forecast.

- Continued policy support may yet be necessary to secure a complete economic recovery. A simultaneous recovery in both supply and demand provides a basis for policy to ‘lean loose’. In this environment, supply is likely to be more responsive to demand conditions than normal, meaning capacity is likely a little greater than perhaps suggested in official data. Arresting momentum in the recovery could also risk a larger permanent output loss, given the stronger link between scarring and the speed of the recovery. In the near term, higher inflation expectations create a risk that may subsequently require concrete action to contain. But, for now, we think policy should err on the side of providing more rather than less support.

- With monetary policy space also heavily constrained, policy must now plan for fiscal capacity to play a greater role in macroeconomic stabilisation. This is likely key if policy is to be able to respond effectively in crises to come.