The COVID-19 pandemic and policy responses to it have continued to dominate global economic developments over the past year. Although the virus has followed a far more severe course than expected this time last year, the global economy has performed slightly better. Around the world, households and firms have adapted to life with the virus, and although the pandemic is not over, economies have become more resilient. In this chapter, we consider the global economic outlook and the kay challenge ahead: turning the economic rebound seen so far into a full and complete recovery.

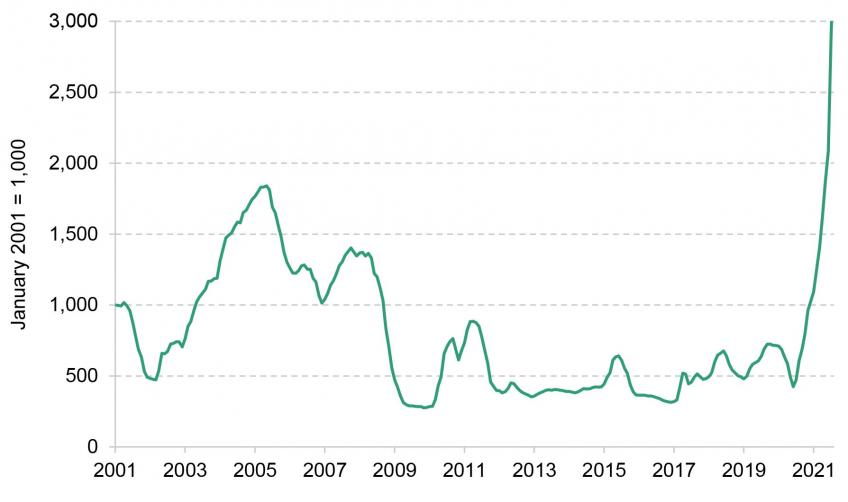

For the rest of 2021, supply constraints will continue to impinge on growth. Along with other transitory factors, these point to higher inflation rates for some time. However, globally there is still a lot of slack visible in labour market data, which suggests that there remains both upside and downside inflation risk.

The risk of a major fiscal tightening, as happened after the 2008−09 crisis, is low and financing conditions are likely to stay benign. After such a deep recession, the risk of financial turbulence remains high, and so central banks will proceed only cautiously to an exit from their extraordinary pandemic-era support. One pressing issue for policymakers is ensuring that the reserves built up by households and companies during the pandemic are put to productive economic use, rather than just pushing up asset prices.

Figure 1. Harper Petersen freight rates (January 2001 = 1,000)

Notes and sources: see Figure 1.10 of IFS Green Budget 2021.

Key findings

- The pandemic is not over, but economies are now more resilient. Some vulnerable areas such as international travel will remain well below normal for some time. However, vaccination campaigns have reduced the likelihood of future lockdowns. As households and companies adjust, the link between mobility and economic activity is weaker.

- The rebound can become a recovery. Globally, households and companies have built up reserves, which they could use to spend and invest. But savings could also end up inflating asset prices rather than boosting the real economy. Governments should think carefully about policy levers that might encourage these reserves to be put to productive use.

- For the rest of 2021, supply constraints will continue to impinge on growth. In an optimistic scenario, shortages merely delay the recovery and trigger additional investment in the meantime. In a pessimistic scenario, lower profits put a further dent in firms’ balance sheets and weigh on growth for longer.

- Supply–demand mismatch, rebuilding profit margins, hot real-estate markets, sensitive price expectations and the green transition all point to higher inflation rates for some time. However, globally there is still a lot of slack visible in labour market data, which suggests that there remains both upside and downside inflation risk.

- The risk of a major fiscal tightening, as happened after the 2008−09 crisis, is low. Governments will phase out the extraordinary support provided during the pandemic over the coming months. However, deficits will stay higher than pre-pandemic as many governments step up public investment. Longer term though, the debate about the need, or otherwise, to bring public debt down is likely to return.

- Financing conditions are likely to stay benign. After such a deep recession, the risk of financial turbulence is high. However, central banks will proceed cautiously towards the exit from their extraordinary monetary support during the pandemic.