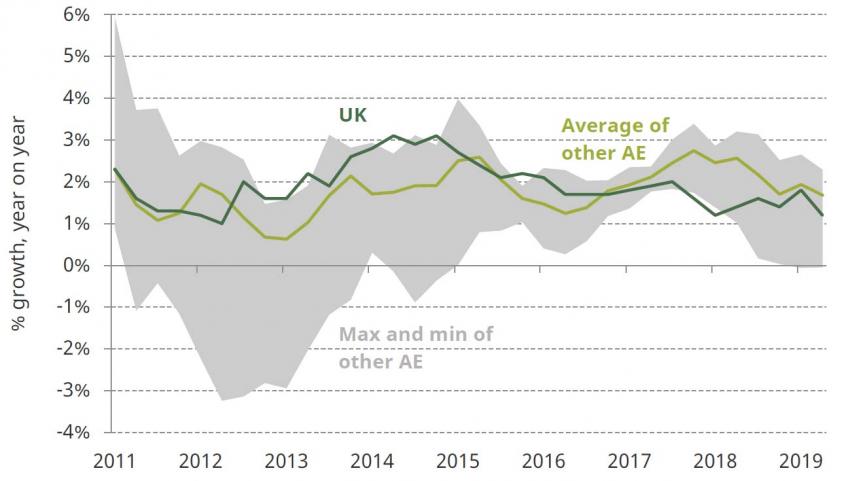

The overall outlook for economic growth, and its constituent parts, underpins any fiscal event, with implications for the public finances, public spending, taxation and living standards. Growth in the size of the UK economy – known as gross domestic product or GDP – has averaged 1.3% (on an annualised basis) over the last four quarters. That is somewhat below its potential rate of 1.4% (as estimated by the Bank of England) and the 1.5% growth rate for 2019 that we forecast in last year’s Green Budget, and well below the average of 2.0% per year between 2010 and 2015.

While global trends play a role in this underperformance, the biggest force weighing on the UK economy seems to be uncertainty surrounding when and how – or whether – it will leave the European Union. In this chapter, we analyse how the different elements of the UK economy have performed since last autumn, highlighting the resilience of consumer spending and the poor performance of business investment. We show that the type of uncertainty that Brexit entails – prolonged and with repeated ‘deadlines’ for a resolution that has not yet materialised – has been especially damaging to business investment, and another year of uncertainty has imposed broader costs on the UK’s economy.

The UK has been hampered by low productivity and investment since the crisis, and these trends have been exacerbated by the referendum. Meaningful improvement in potential UK growth will require a more robust policy outlook, a revival in private investment and stronger productivity growth.

Year-on-year GDP growth in the UK and other advanced economies

Note: Countries included as other advanced economies are France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the US. Max/Min series do not include UK.

Key findings

- UK economic weakness has been both more longstanding and more extensive than in other major economies. Growth in the UK has been weaker than in other G7 economies since 2016, volatile through this year, and averaged only 1.3% in the second quarter of 2019, compared with the same period last year.

- Unemployment is currently below its natural rate equilibrium, even while realised growth remains below potential. This reflects weakness in productivity and investment since the referendum, but resilience in employment and household spending. Growth has become more consumption-driven as a result.

- Private sector investment is particularly weak. Business investment has witnessed its most sustained period of weakness outside of a recession and is now the lowest in the G7.

- The sharp divergence between growth in UK private sector investment and that in other developed economies coincides with the post-referendum period, reflecting a sharp and sustained increase in economic uncertainty. This has increased the perceived risk associated with investments and reduced quarterly private investment by around 15–20% compared with if business investment had continued to grow in line with pre-referendum trends. Ongoing worries about the risk of a ‘no deal’ Brexit are particularly damaging to investment.

- High employment, a falling exchange rate and low levels of investment have already led to unit labour costs rising sharply. Low investment now will lead to low growth in productivity and earnings in the future.

- GDP is roughly 2.5–3.0% (£55–£66 billion) below where we think it would have been without Brexit. Based on pre-crisis forecasts and global economic performance in 2017 and 2018, we suspect the UK has missed out almost entirely on a bout of global growth, which would normally have boosted exports and investment.

- A recovery in growth from here is likely to require a profound reduction in policy uncertainty. Without investment and improvements in labour productivity, growth is likely to slow further.