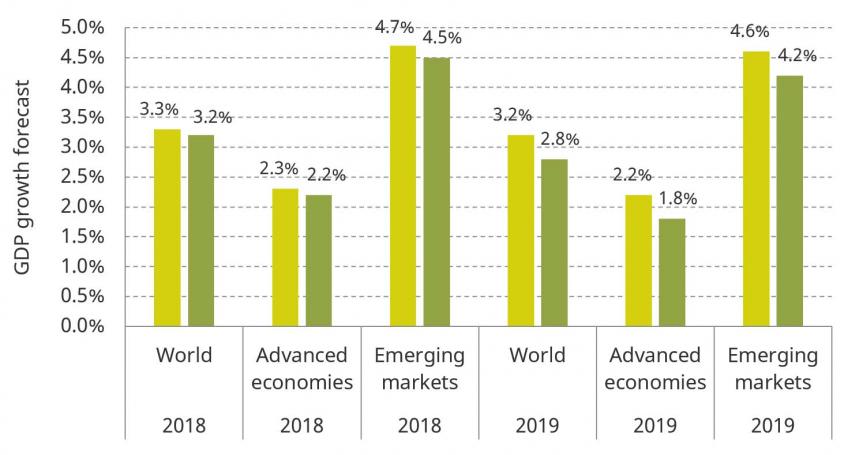

The phase of synchronised growth the world enjoyed in 2017 and early 2018 has come to an end. Following two years when the global economy finally expanded faster than its long-run average of 3.0%, growth looks set to slow to 2.8% in 2019. This is a significant disappointment compared with forecasts from this time last year, which predicted global growth of 3.2% in 2019.

The global downturn has also changed the policy narrative; after years of gradually normalising monetary policy following the response to the financial crisis, central banks are cutting interest rates again. And because government borrowing costs are so low at the moment and the effectiveness of yet more central bank intervention to combat an economic downturn is in doubt, fiscal policy trends could also move to a more expansionary setting.

In this part of Citi’s contribution to the Green Budget, we analyse the causes of the global downturn and discuss the role of fiscal and monetary policy in addressing it. We argue that there are two big forces buffeting the global economy. Slower domestic growth in China as it transitions to a consumption-led economic model has had ramifications for much of the rest of the world. And the trade wars that US President Donald Trump has started against both China and the rest of the world have both imposed a direct penalty on global trade growth and raised uncertainty in the global economy.

GDP growth forecasts in Green Budget 2018 versus latest actual and projections, 2018 and 2019

Source: IFS Green Budget 2019 and Citigroup Global Economic Outlook and Strategy (July 2019).

Key findings

- The global growth outlook has deteriorated. Having grown by an above-average 3.2% in 2018, world output growth looks set to fall to below-average 2.8% in 2019 and stay there in 2020. The downturn is spread across advanced economies and emerging markets, but focused on the manufacturing hubs so far.

- China’s rebalancing hurts its supply chains. Export- and investment-led growth allowed China to become the world’s second economy, but reached financial and environmental limits. The inevitable shift towards domestic consumption and innovation slows growth in China and its supply chains, including Germany and Japan.

- US trade wars compound China’s troubles and sow uncertainty. US President Donald Trump’s administration is imposing tariffs, hurting exports in the targeted economies and raising prices at home. More importantly, business investment suffers globally as uncertainty about supply chains spreads.

- In the medium term, we forecast that US growth will remain strong, China’s growth rate will slow, and parts of Europe will flirt with recession. While global trade and manufacturing are in recession, domestic demand remains resilient. The US still enjoys large fiscal stimulus, but as the boost from this winds down its growth rate will slow to potential soon. Chinese growth is falling gradually. In Europe, Germany and Italy are close to recession, but France and Spain are more resilient.