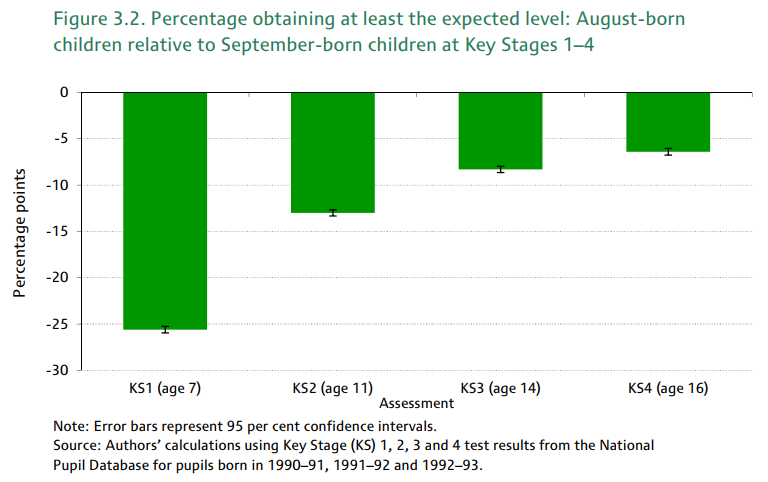

Research from the IFS and others consistently finds that, on average, pupils born later in the academic year perform significantly worse in school than those born at the start of the academic year. As well as achieving lower test scores and assessments from teachers, on average, children’s confidence in their academic ability is also affected. Many parents of summer born children are therefore concerned about how well their child performs at school, and some have called for more flexibility in the timing of entry to primary school as an appropriate policy response. (Of course, such a policy may have other goals, aside from reducing differences in educational attainment, but it is this objective that has been cited in the latest debates.)

These concerns seem to have been heeded by the government: the childcare minister, Elizabeth Truss, has recently expressed concern that local authorities are not doing enough to offer parents flexibility over when children can start school, and guidance issued by the Department for Education in July highlights that there is no statutory barrier against delayed entry (where a child starts school a year later with a lower age group, becoming the oldest in the class), as well as the more common deferred entry (where children start school later but join the year group that is correct for their age) .

It is, of course, understandable that parents are concerned about the welfare of their own children. But the government has wider objectives; they must think about how the education system affects all pupils, as well as particular subgroups, and here the decision is not always so clear cut.

We know that, on average, deferred entry is not in the interests of summer-born children. IFS research has compared the performance of children who start school across areas of England which operate different admissions systems. We find that deferred entry to school does not close the gap in educational attainment between those born at the start and end of the academic year. In fact, on average, those born later in the year benefit slightly from starting school at the beginning of the academic year with their older peers, rather than joining them up to a year later. This is because the benefit of additional time in school more than outweighs the disadvantage of starting school slightly younger.

Assessing the impact of delayed entry to school is less straightforward, as this practice is not commonly observed in England. It is possible that it would benefit some of those who become one of the oldest in their class, rather than one of the youngest. This flexibility may have adverse consequences for other children, however: those that do not delay entry will become the youngest in the class and may have peers that are over a year older. This increase in the age-range of pupils may make teaching harder, and may simply shift the problem of lower attainment and self-belief to other children. Moreover, there are still differences in attainment between children born at the start and end of the year in countries in which it is common for children to delay or defer entry to school, and some that follow such policies (e.g. Scotland) are actually thinking about reducing or removing these flexibilities.

More importantly, IFS research has concluded that it is the age at which a child sits a test, rather than the age at which they start school, that is the main determinant of differences in attainment between those born at the start and end of the academic year. This suggests that a policy of providing age-adjusted test scores, so that a child receives feedback about their attainment relative to others their age, rather than others in their class, would help address the educational inequalities we observe. Children’s self-belief may also improve with timely and regular feedback of this kind, although some differences, such as the higher proportion of summer-born pupils identified as having special educational needs, may require additional policy responses. Moreover, unlike other policies designed to reduce these attainment gaps, providing age adjusted test scores benefits all children, as everyone is given appropriate feedback; older children that should receive more support will be identified, and younger children that are doing well for their age will be reassured.

It is important to note that IFS research cannot be used to conclude whether increasing the statutory school starting age from 5 to 6 or 7 (as suggested by a group of educationalists today) would be beneficial for children or help address the inequality between those born at the start or end of the academic year: a policy of this kind has not been trialled in England. Our research suggests, however, that within the confines of the current system, allowing deferred or delayed entry to school is highly unlikely to eliminate the disadvantages faced by summer-born children – as we find that it is age at test, rather than age of starting school, that matters most – and indeed may be detrimental to the school experiences of others.