An important part of the UK policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been to try to help ensure key workers with children have access to sufficient childcare. Children of key workers are allowed to continue attending school and childcare settings, and both schools and early years providers are working to ensure wraparound care outside of school hours. Non-working partners, or those working from home, are also expected to provide childcare for key workers in some families. This observation discusses remaining areas of concern on why key workers still might face childcare-related constraints that restrict their ability to work at this critical time, and we highlight short-run policy changes that can help.

Core Policy Implications

1. Around one in five key worker families with pre-school children make use of informal care by grandparents. These arrangements are much less likely to be feasible in the current crisis.

2. Key workers’ demand for formal childcare taking place in nurseries and other settings is therefore likely to rise. However, the significant cost of childcare above the free hours offered is likely to affect key worker family budgets. Policymakers might consider extending free childcare entitlements by increasing the number of free hours per week or by extending the scheme to younger children.

3. However, even with extra financial support, some key workers might still struggle to access the childcare they need. While most early years settings had some spare capacity before the pandemic, staff shortages and a loss of income from fee-paying parents will make it hard for settings to operate and stay afloat. Many settings might also struggle to replace the ‘wraparound’ care done by grandparents outside of core hours. This will be particularly important since many key workers need to work out of normal hours or to work extra shifts.

Childcare Arrangements for Pre-school Age Children

Parents make use of a range of childcare options for pre-school age children, including formal centre-based care (such as nurseries, crèches, and playgroups); childminders; and informal care by grandparents.

At younger ages, fewer families use childcare, but the entitlement to a free part-time childcare place for all 3- and 4-year-olds and some 2-year-olds in England means that formal centre-based care is the dominant arrangement at older ages (analogous schemes operate in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). According to government statistics, at least 90% of 3-year-olds in England currently receive some free childcare in a centre-based setting. Settings have been asked to stay open where possible for the children of key workers to attend, but other children are expected to stay home. Even so, settings will continue receiving funding for these free hours of all children enrolled there, irrespective of whether a child attends or not (or whether their parent is a key worker or not).

However, while most families use some centre-based childcare, many also relied on other types of care before the pandemic, which could prove challenging to replace. Like centre-based settings, registered childminders can still operate, but social distancing, self-isolation and caring for their own families will make this more challenging during the crisis. The most pressing problems face families where grandparents help with childcare; government advice suggests that grandparents, who are more likely to be older and more vulnerable to the virus, should not be providing childcare.

Childcare Arrangements for Key Worker Families

Previous analysis has highlighted that key workers have different demographics to other workers: they are more likely to be female and more likely to have young children at home. They also use different childcare arrangements than workers in non-key industries.

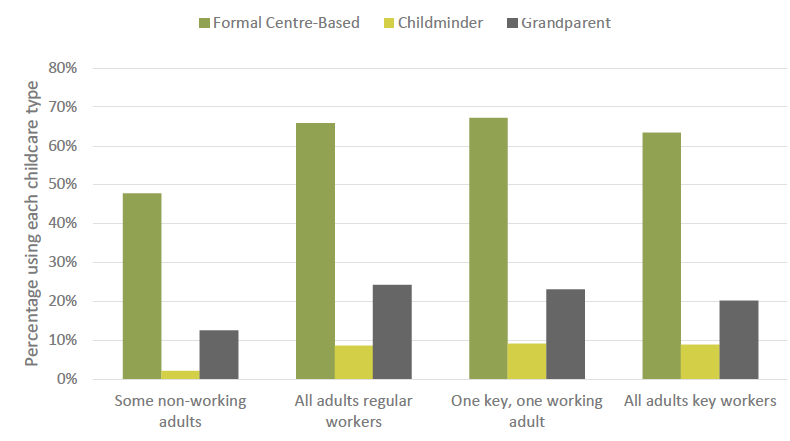

Figure 1. Childcare usage of 3-year-olds by their household’s working status

Figure 1 shows the childcare used by 3-year-olds in different types of families (as recorded in the Millennium Cohort Study; as described in the data note below, this data is relatively old but is a uniquely reliable resource for analysing patterns by child age and for key worker families specifically). We consider families based on whether they contain someone not in work, and whether the working adults are regular or key workers.

In 2004, just over half of 3-year-olds lived in a household with at least one parent who was not in paid work. Another 28% of children lived in households where all adults were in regular (non-key) work. Of the 17% of children living with at least one key worker, around a quarter lived in families where all adults had critical jobs.

These household combinations matter. Families where all adults are in work – whether regular or key – are much more likely to use formal childcare and childminders. Most strikingly, they are around twice as likely as other families to rely on grandparents for at least some childcare; fully a fifth of 3-year-olds in families where all adults are key workers were looked after by their grandparents at least some of the time. There is some evidence that care by grandparents has become more important over time (see data note); this suggests that the true figure today could be higher still.

Almost 10% of fully key-worker families make use of childminders, which might also be less able to operate during the crisis. These families will be left looking to the centre-based childcare sector to replace this flexible childcare they have previously relied on.

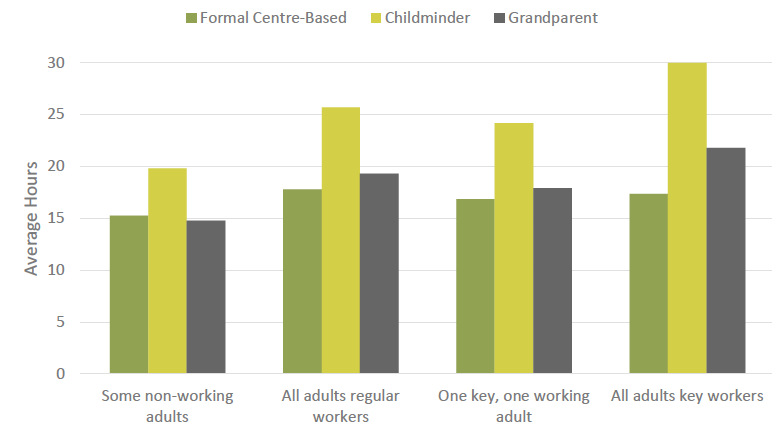

Not only are families where all adults are key workers more likely to receive care from grandparents and childminders, they also use these types of care more intensively than other families.

Figure 2 shows the average weekly hours of childcare among users of each childcare type, splitting by the family types outlined above. Where they provide any help, grandparents provide, on average, 22 hours of childcare to 3-year olds in families where all adults are key workers. Among fully key-working families who use childminders, the average family receives 30 hours a week of childminder care for a 3-year-old.

Figure 2. Average weekly childcare hours, by partner and key worker status

The additional hours of childcare used by key worker families might also reflect the fact that key workers often work out of normal hours. We note that pre-crisis, almost 60% of key workers worked more than 30 hours/week (the free childcare limit for 3 and 4 year olds); of these, half worked more than 40 hours a week. Among lone mother households (the group for whom we have reliable data on working patterns), around two thirds regularly work outside of core hours on evenings, nights, and weekends (this share is closer to one half for non-key worker lone mums).

During the crisis, key workers are likely to be required to work additional shifts to meet the surge in demand for critical healthcare and demand for other key services. Hence the flexibility of child care provision – not just the total hours available – will be an important consideration.

The Provision of Childcare

The Department for Education and devolved governments have asked all childcare providers to remain open where possible, though initial surveys of the sector suggest that many providers are finding this financially and logistically difficult. Those providers that do continue to operate need to be in a position to meet extra demand from key worker parents, who might be substituting away from grandparent care, or are faced with a need to work extra shifts.

Individual settings are likely to respond quite differently to this change in demand, depending on their pre-virus capacity and the extent to which it is challenged by staff shortages, the amount and flexibility of childcare that their clients demand, and their financial position.

Many childcare settings had spare capacity before the virus; government figures from last year show that around 60% of maintained settings, 70% of private settings and 50% of childminders had extra spaces. Staff shortages will certainly reduce this capacity, but the relevant question for nurseries will be whether they see a bigger overall drop in staff supply or in childcare demand. Nurseries where many staff need to self-isolate simultaneously could face major challenges in staying open.

Even among childcare providers who have spare capacity, a crucial question will be how many of their clients are in key worker families, and how much flexibility they can offer to them. Replacing the wraparound care that grandparents previously supplied might be especially difficult; pre-virus, only around 30% of group-based settings offered regular provision outside of school hours.

Financially, centre-based settings (which rely on employees) and childminders (who are mainly self-employed) face two different government job support schemes, which will impact their ability to respond to changes in demand. Some nurseries might choose to furlough some employees in order to receive financial support from the Government (working shorter hours is not possible here). Most childminders will benefit from the generous package of support for self-employed workers announced last Thursday (which allows them to continue earning in the meantime). But since only 15% of childminders have an assistant, reducing staffing won’t be an option: they face a choice between staying open to serve fewer children, or closing altogether for the time being. Childminders are also less likely to accept free entitlement funding, meaning they will see less of their regular income continued over the next few months.

Surveys of early years providers bear out these concerns: they already show many unable to operate during the current crisis. Meeting demand for extra hours beyond the normal working day will also be a significant challenge on top of this.

There are a number of potential policy responses that might help early years providers respond to these changes in demand from key workers. Governments could relax eligibility restrictions on the free entitlement for key workers, providing income to early years providers and potentially valuable support to key workers. This could include increasing the entitlement for key working parents from 30 to 40 hours, extending the 2-year-old entitlement to key workers (not just the 40% most disadvantaged) or allowing it to cover younger children. Other policies and responses could include increasing the limit for Tax Free Childcare for key workers and enabling schools to take in younger siblings from age 2 (as many are already doing).

Although potentially costly, working within the existing systems of childcare support could help the government to implement changes quickly and provide assistance to key workers struggling to modify their childcare plans. Every extra hour key workers can work could help get the country through the crisis.

Data Notes

Except where otherwise noted, we have used data from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) to prepare figures on childcare use. The MCS surveyed children born in 2000-01 at nine months, three years, and five years old. This means that data for children at age 3 was collected in 2003-04.

The reason we are relying on this relatively old dataset is that it combines detailed information about parents’ occupations (which allows us to identify key workers) with excellent data about childcare use among children. Since the MCS specifically focused on questions about children’s lives, it is able to capture childcare use much more accurately than more recent but general surveys (such as Understanding Society). Meanwhile, more recent surveys with very good childcare data (e.g. the Study of Early Education and Development) don’t have as much detail on parental occupations as we need to classify key workers. (See our previous observation for a full description of how we do this).

Of course, since 2003-04 the government has substantially increased the generosity of its support for formal childcare. As a check on the relevance of this data, we have compared it to two other sources of childcare data: data from Understanding Society at age 3 (collected in 2018) and summary statistics for 2- to 3-year-olds produced by researchers using the Study of Early Education and Development (collected in 2014-15). Importantly, the latter survey does not distinguish care by grandparents from other informal care by relatives and friends. The summary statistics also measure the main type of care among childcare users; the researchers find that about 5% of children never use childcare between ages 0 and 3.

Comparing these three data sources, we find that the 56% of 3-year-olds who use formal childcare in the MCS compares to 47% in Understanding Society and to 63% of 2- to 3-year-old childcare users in the SEED study. In the MCS, 5% of 3-year-olds use childminders, compared to 10% in USoc and 9% in SEED. The use of grandparent care seems to have increased over time: the 18% of 3-year-olds in the MCS cohort who receive care from grandparents compares to 28% in USoc and 26% in SEED.

What this means is that the precise numbers of who is using formal care, and how much they use, are less important than the overall pattern: key workers are likely to need flexible childcare, to have used grandparents for some of this care, and to now need alternative sources of childcare that will support their working hours during the crisis. To the extent that the MCS underestimates grandparent care especially, the challenges that we set out in this observation are likely to be even more significant today.