Methods and data

Early years

There are a number of data sources for spending on the early years, each covering a slightly different set of spending and each available for a different period of time. As with any exercise to construct a historical series of spending, there will inevitably be limitations in the data quality and consistency from year to year. We have prioritised building a consistent series as far as possible, including using imputation where warranted.

Spending on the free entitlement

In constructing a series for spending on early education, we combine information from several data sources. We use budget data from the Section 251 summary budget tables, which we cross-check against the Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG). We also use data on spending (out-turns) from the Department for Education’s LA and school expenditure series and related official statistics. Finally, in the earliest years of the free entitlement (1997–98 and 1998–99), we use data on reported central government spending on nursery vouchers through the Nursery Education Grant.

Spending per hour and the hourly funding rate

Our focus is on constructing a measure of spending that is consistent over time and accurately reflects the amount of resource that the public sector puts into the free entitlement. This is clearly influenced by the core hourly funding rate (used in the DSG since 2012–13), but the two are not the same.

In the Early Years National Funding Formula, the core funding rate reflects the minimum amount that central government allocates per hour of care. Around 95% of this is passed on to providers by local authorities (this pass-through rate has risen over time in response to policy changes).

Our wider measure of spending also includes spending on a range of uplifts and supplements, such as the Early Years Pupil Premium, the high needs supplement, the maintained nursery supplement, and any additional spending that local authorities choose to take on to support their early years sector.

Detailed methodology

The budget data are based on the Individual Schools Budget for nursery schools (2001–02 to 2009–10) and for early years (2010–11 to 2019–20 and 2022–23). From 2012–13 onwards, they net out spending on the 2-year-old free entitlement as well as some elements of health-related and central spending.

Section 251 out-turn data are calculated as net current spend from nursery schools and private, voluntary and independent (PVI) providers plus net current central spend on nursery schools.

We believe that the data series has the following limitations:

• Budget data between 2001–02 and 2009–10 likely exclude spending on nursery classes.

• Spending figures from the Section 251 returns do not explicitly include spending on free entitlement hours delivered by PVI providers from 2013–14 onwards.

Since we do not believe that spending was overstated in any of these years, we use the most complete measure of spending available in each period up to 2012–13 to provide the most accurate figures possible. Since 2012–13, the trends in the budget and SFR52 spending data have tracked each other closely (and, since 2015–16, the free entitlement block in the DSG has tracked both of these series as well). We have preferred the budget measures for these years to avoid another break in the data series. This means that our figures do the following:

• 1997–98 to 1998–99 – Use spending on the Nursery Education Grant.

• 1999–2000 to 2000–01 – There are no spending data in 1999–2000, and spending data in 2000–01 are incomplete. We do not report spending figures for these years.

• 2001–02 to 2009–10 – Use the Section 251 spending data as they explicitly include spending on PVI provision of the free entitlement (while the budget data are likely to exclude spending on nursery classes).

• 2010–11 to 2012–13 – Use the budget data (which now relate to all early years spending) as they are likely to be more comprehensive.

• 2013–14 to 2019–20 and 2022–23 – Continue to use the budget data to provide a more consistent series. (Budget and SFR52 spending data track each other closely.)

Changes during the COVID-19 pandemic

To ease the pressure on the education sector during the COVID-19 pandemic, local authorities were exempted from completing their regular Section 251 reporting in 2020–21. To arrive at an estimate of spending in this year, we therefore use information from the DSG (which was available for 2020–21).

To make the estimate more consistent with our wider series of education spending, we use statistical models to assess the relationship between the DSG and our preferred Section 251 series in previous years. Taking into account both trends in both series over time and changing population, we use this historical relationship to adjust the 2020–21 DSG numbers to more closely match our existing series.

Spending in the tax and benefits systems

We also consider wider measures of support for early education and childcare, namely through spending on childcare subsidies delivered through the tax and benefits systems such as employer-supported childcare vouchers, tax-free childcare, and the childcare element of working tax credit and universal credit.

Relief through the tax system

As for the free entitlement, we have pieced together a historical record of spending based on data from a number of sources. In the tax system, data on forgone tax and National Insurance revenues are first available from 2007–08 (although employer-supported childcare vouchers were first introduced in 2005). We combine data from table 2 of Stewart and Obolenskaya (2015) and from HMRC’s Ready Reckoner, which shows the costs of various tax reliefs. In the one year where the two data sources overlap, there is a considerable difference between them; however, the figures from HMRC for 2012–13 are more consistent with the rapid growth in spending from previous years, so we prefer the official government source in that year. We also avoid analysing spending around the point where the data source changes.

One complication is that, since these are national policies, spending figures are reported for the whole of the UK. In order to be consistent with the rest of our data on early years spending, which focus on England, we attribute a portion of these UK-wide costs to spending in England based on the English share of the under-15 population in the UK.

In more recent years, tax-free childcare has become increasingly important as the intended replacement to vouchers. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one data source for the cost of tax relief on tax-free childcare: the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

Subsidies through the benefits system

On the benefits side, we again rely on Stewart and Obolenskaya (2015) for historical data. For more recent years, we use HMRC’s statistics on awards through working tax credit (finalised where available). As with the tax system, we use population shares to attribute a portion of UK-wide spending to England.

In the period where Stewart and Obolenskaya’s figures overlap with data from HMRC’s working tax credit statistics, there is a very close correspondence between the two series; discrepancies are likely the result of rounding. We therefore prefer to use data from HMRC to be as consistent as possible with later figures, so we follow Stewart and Obolenskaya from 1997–98 through 2007–08 and the HMRC statistics thereafter.

In the last few years, working tax credit has become less important in the system as new and existing claimants are brought into universal credit (UC). Unfortunately, there is no consistent information available on spending on the childcare element of UC over time.

There is, however, information on expenditure on cost subsidies via UC in one year, 2021–22 (Department for Work and Pensions, 2022). We combine information on the average payment for the childcare component with the actual number of families receiving some support for childcare expenses (published monthly by the Department for Work and Pensions via the interactive Stat-Xplore tool) to estimate the total cost in 2021–22.

For other years, we assume the average payment is the same in real terms as in 2021–22 – the only year data are available – and combine with the published statistics on the number of families claiming.

While this approach has limitations (for instance, if the average payment has changed over time), it is the most sensible estimate we can make with the very limited data available.

Measuring changes in childcare providers’ cost

Typically, we adjust cash-terms spending over time for rises in the general price level (i.e. inflation) using the GDP deflator. This measures economy-wide inflation, including goods and services purchased by the government, and is the standard metric for converting spending by government into real terms.

However, early years providers’ costs are different from those faced by the government as a whole. We might expect this to matter more at a time of historically high inflation; therefore we also present real-terms funding as adjusted by an index of prices facing childcare providers.

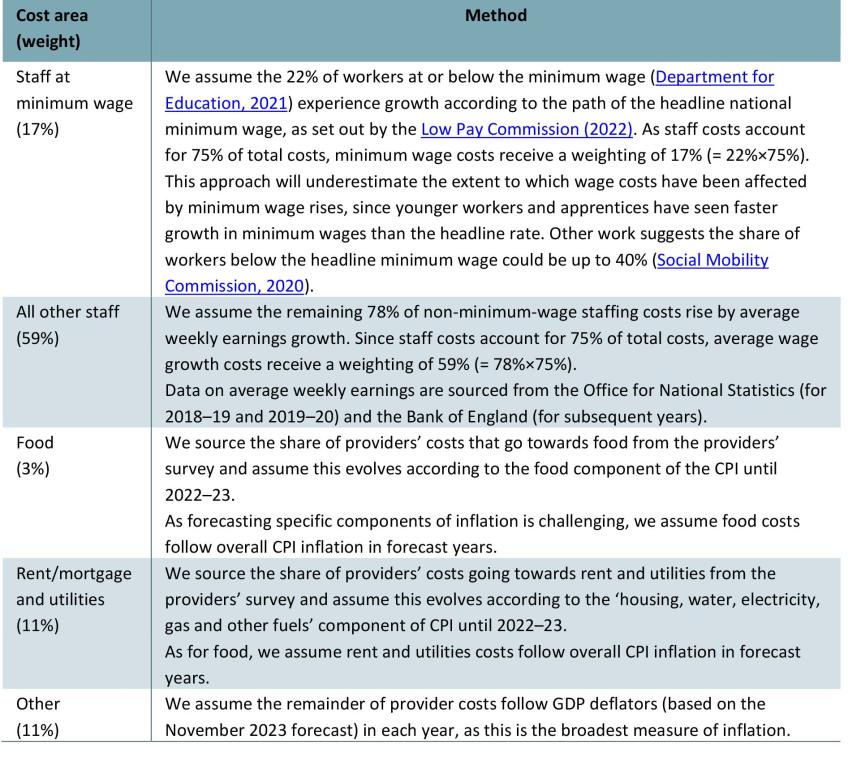

To construct the childcare providers’ price index, we take a weighted average of the prices of the main components of provider expenditure (namely, staff costs, materials, rent and utilities), with weights reflecting each component’s share of providers’ overall costs (sourced from the Childcare and Early Years Providers Survey in 2019). Table 1 provides an overview of the measures and weights used.

The path of future inflation is still highly uncertain. Our index provides an illustration of how the prices faced by childcare providers might change over the coming years.

Table 1. Components and weighting of the index of prices facing childcare providers

Note: Adapted from table 2 in Drayton and Farquharson (2022). ‘The providers’ survey’ refers to the Childcare and Early Years Providers Survey in 2019. All providers’ cost shares are sourced from this survey. Weights do not sum to 100% because of rounding.

Source: The share of workers affected by the national minimum wage is sourced from Early years funded entitlement cost changes forecasts, England: spending round 2021 to 2022.

Historical national minimum wage rises are sourced from National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates; forecasts come from Low Pay Commission (2022).

Past average wage growth is taken from Office for National Statistics, Average weekly earnings time series and Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report – August 2023; forecasts of average wage growth come from the same Bank of England report.

Headline CPI and individual components of CPI come from Office for National Statistics, Inflation and price indices; forecasts of CPI are sourced from Bank of England, Monetary Policy Report – August 2023.

GDP deflator historical data and Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts are taken from GDP deflators at market prices, and money GDP November 2023.

Forecasting free entitlement funding

To forecast spending out to 2027–28 (the final year of the forecast horizon for the March 2023 Budget), we combine information from the Budget with ONS population projections, historical data on the take-up of different entitlements, and data on funding allocations from the Dedicated Schools Grant.

The Budget set out the total amount of additional funding for the free entitlement until 2027–28, covering both uplifts to the funding of existing entitlements and spending on the new programmes. This lets us analyse how total funding for the free entitlement is set to change.

In order to analyse what the Budget means for existing entitlements, it is also useful to model how the total free entitlement budget might be allocated across the different programmes. This is an indicative rather than an exact process, but it helps to illustrate what the Budget promises could mean for providers.

First, we need to allocate the Budget uplift across existing and new entitlements. The Chancellor promised a funding uplift worth £202 million in 2023–24, rising to £288 million the following year. This money will raise the funding rate for existing entitlements.

• For 2023–24, the government has announced (Department for Education, 2023) that the uplift will raise average funding rates for 3- and 4-year-olds to £5.62 an hour from September, and for 2-year-olds to £7.95.

• For 2024–25, we know that the rate for 2-year-olds is set to rise to £8.28 in cash terms. Using our forecast for part-time-equivalent places, we work out how much of the uplift this will use up and calculate what the rate for 3- and 4-year-olds could be based on the remainder.

• We then assume that these hourly funding rates are protected in real terms going forward. Coupled with projections for part-time-equivalent places in each entitlement, this allows us to calculate the total budget.

• We then subtract the amount of additional funding implied by these plans from the total funding set out in the Budget scorecard, and assume that the difference will all be used to fund the new Budget entitlements. This leaves just under £4 billion for the new entitlements in 2025–26, the year roll-out is completed.

We have two main methods for calculating school spending per pupil. The first relates to school-based spending per pupil, whilst the second additionally includes spending undertaken by local authorities. Here, we detail the underlying assumptions, methods and data sources for each measure.

School-based spending

Our measures of school-based spending per pupil are shown for both primary and secondary state-funded schools. The methods and data used for calculating these figures are updated from Belfield and Sibieta (2016).

Spending includes all spending undertaken by state-funded schools, including academies and free schools where possible. Given that the data do not break expenditure down by pre-16 or post-16 categories, this will include spending on school sixth forms. We exclude special schools because funding arrangements for these schools are more complex and driven more by the needs of individual pupils.

We make use of four main data sources for expenditure: CIPFA Education Statistics Actuals between 1978–79 and 1999–2000; schools’ Section 52/251 returns between 1999–2000 and 2009–10; Consistent Financial Reporting data from 2010–11 to 2021–22; and academies’ Accounts Returns from 2011–12 to 2021–22.

The CIPFA Education Statistics Actuals compile data returned by each local authority (LA) in England and Wales. This includes all expenditure by LAs on schooling. Prior to Local Management of Schools in 1990, this expenditure was primarily spent directly by the LA. After 1990, this expenditure is the amount allocated to schools directly through the LA formula plus the amount spent centrally by the LA. The CIPFA data thus combine school-based and LA-based expenditures. We are unfortunately not able to separate these two components.

From 1999–2000 to 2009–10, we use the Section 52/251 data. These data are compiled from the returns of individual schools about their levels of funding and expenditure each year. Differences between funding and expenditure may emerge when schools do not spend their entire budget. As we are interested in the amount of money spent on pupils’ education, we use the expenditure data wherever possible. Importantly, this excludes central spending by LAs. As such, the data from Section 52/251 returns represent school-based expenditure. In all cases, we divide total expenditure in each financial year by the number of full-time-equivalent pupils in the January within the financial year to create per-pupil measures of school expenditure (for example, January 2003 for financial year 2002–03).

From 2010–11 onwards, we make use of Consistent Financial Reporting (CFR) data downloaded from the Schools Financial Benchmarking Service and annual performance tables. Spending per pupil is defined as total net expenditure divided by the number of full-time-equivalent pupils. Net expenditure is defined as total expenditure net of income from catering, teacher supply insurance claims, community-focused income and capital expenditure from revenue account. These data are for maintained schools and extend up to 2021–22.

Academies’ Accounts Returns (AAR) data are available from 2011–12 to 2021–22 from the Schools Financial Benchmarking Service and the income and expenditure of academies. This means all academies are missing from the data for any period between their foundation or conversion and 2011–12. We do not include schools where information is only available for part of the financial year. We only use spending recorded for individual academies, which will exclude any money retained centrally by multi-academy trusts. We use a similar definition of net expenditure to that used in CFR data. In particular, we define net expenditure as total expenditure minus income from catering, teacher supply insurance claims and capital expenditure from revenue account. Unfortunately, community-focused income can only be deducted for 2011–12.

A number of inconsistencies mean the spending per pupil will be higher for academies than for similar maintained schools. First, academies’ financial data relate to the academic year rather than the financial year. Second, academies’ expenditure will include funding for services provided by LAs for maintained schools (particularly in the years 2011–12 and 2012–13). Third, sponsor academies tend to be located in more deprived, urban areas, which typically receive higher levels of funding. This means the exclusion of academies before 2011–12 will likely depress the recorded measure of overall spending below its true level and their inclusion afterwards will create an artificial jump in spending per pupil (particularly for secondary schools).

To combine our data sets, we apply the LA-level expenditure-per-pupil growth rates implied by the CIPFA data to extrapolate the Section 52/251 data backwards from 1999–2000 (for unchanged local authority boundaries). This creates an LA-level data series for school-based spending from 1978–79 through to 2009–10. This provides a broadly consistent measure of school-based spending per pupil between 1978–79 and 2021–22.

Importantly, data for 2020–21 and 2021–22 reflect the effects of the pandemic and the closure of schools to most pupils during much of each year. Schools also received temporary extra funding for exceptional costs and education catch-up spending. Expenditure may be depressed in 2020–21 in particular because of reduced spending on some inputs, such as food and energy. In order to focus on trends in core school spending, we deduct COVID-related grants, which totalled about £70 per pupil in primary schools and £80 per pupil in secondary schools in 2021–22 according to the CFR and AAR data.

For analysis of how levels of school spending per pupil differ by levels of deprivation, we link to further school-level data on the share of pupils eligible for free school meals over time. In particular, we use LEASIS data 1993–2009 as per Belfield and Sibieta (2016) and data downloaded from annual performance tables for 2010–18 and underlying data downloaded from ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics’ for 2019 to 2022.

Total school spending

Total school spending is intended to represent all spending by either schools or local authorities on children aged 3–19 in state-funded schools in England.

‘Spending by schools’ is calculated as the sum of (net) individual school budgets, any money delegated to schools for high needs, the Pupil Premium and the Teachers’ Pay Grant. Individual school budgets and high-needs delegated funding are calculated from Section 52/251 out-turn data up to 2012–13 and Section 52/251 budget data from 2013–14 to 2022–23. For years 2010–11 to 2012–13, we additionally include academies’ recoupment funding from Dedicated Schools Grant allocations. Pupil Premium allocations 2011–12 to 2023–24, the Teachers’ Pay Grant and the Teachers’ Additional Pay Grant are based on national allocations. For 2022–23, we also include the Schools Supplementary Grant.

For years 2013–14 to 2016–17, we also add impute values of the Education Services Grant based on the published rate and pupil numbers.

This spending will include funding for delivery of the free entitlement for 3- and 4-year-olds, which cannot be excluded from individual school budgets in most years of data. We are, however, able to exclude funding for 2-year-olds as detailed in table 8 of Section 52/251 budget statements.

‘Spending by local authorities’ is calculated as the (net) schools budget minus any funding provided direct to schools via individual schools budgets or top-ups to providers for high-needs funding. We additionally include the relevant wider education and community budget detailed in Section 52/251 out-turn and budget returns (excluding items 2.3.1 to 2.4).

‘School sixth-form funding’ is based on allocations to school sixth forms as detailed in our 16–18 funding methodology.

‘Extra funding for employer pension contributions’ is based on national allocations to schools for the Teachers’ Pensions Employer Contributions Grant (mainstreamed into the National Funding Formula from 2022–23).

Pupil numbers in state-funded schools are calculated from Department for Education, ‘Schools, pupils and their characteristics’, January 2010 to January 2023. We then additionally include pupils aged 3–4 in private, voluntary and independent settings from Department for Education, ‘Education provision: children under 5 years of age’, January 2010 to January 2023. These are projected to 2024 based on national pupil projections.

Unfortunately, the main data source used (Section 52/251 budget returns) was not collected for 2020–21. We therefore impute figures for this year based on constant real-terms growth between 2019–20 and 2021–22.

School cost index

The school cost index is calculated from 2019–20 to 2024–25. It is the weighted average of growth in teacher pay per head, other staff pay per head and non-staffing costs, with the weights based on the share of total expenditure they represent. Most of the figures on changes to date in pay per head and expenditure shares are taken from Department for Education, Schools’ costs: technical note: 2020 to 2021, 2021 to 2024 and 2022 to 2024.

Teacher pay per head figures are based on a weighted average of paybill per head growth of 2.75% in September 2019, 3.1% in September 2020, 0% in September 2021, 5.4% in September 2022, 6.5% in September 2023 and an assumed 3% in September 2024. The last figure treats the STRB recommendations for 2023 from its 2022 report as a long-term default. Figures assume pay drift of 0.2% in 2021–22, –0.2% in 2022–23 and zero for all other years. Increase in teacher costs includes the rise in employer pension contributions from September 2019. The temporary Health and Social Care Levy for part of 2022–23 is excluded to focus on core trends.

Increases in costs of other staff pay per head are taken from Department for Education, Schools’ costs: technical note: 2020 to 2021, 2021 to 2024 and 2022 to 2024, plus an assumed average pay award of 8% in 2023–24. We assume a figure of 3% for 2024–25 to match the assumption for teachers. As per the schools’ costs note, we also add 0.3% for rising employer pension costs of other staff.

Other costs are assumed to grow in line with actual CPI inflation up to 2022–23 and OBR forecasts for 2023–24 and 2024–25.

As assumed in Department for Education, Schools’ costs: technical note 2022 to 2024, we also add additional amounts for the rising costs of special educational needs provision (0.6% in 2022–23 and 0.5% in 2023–24).

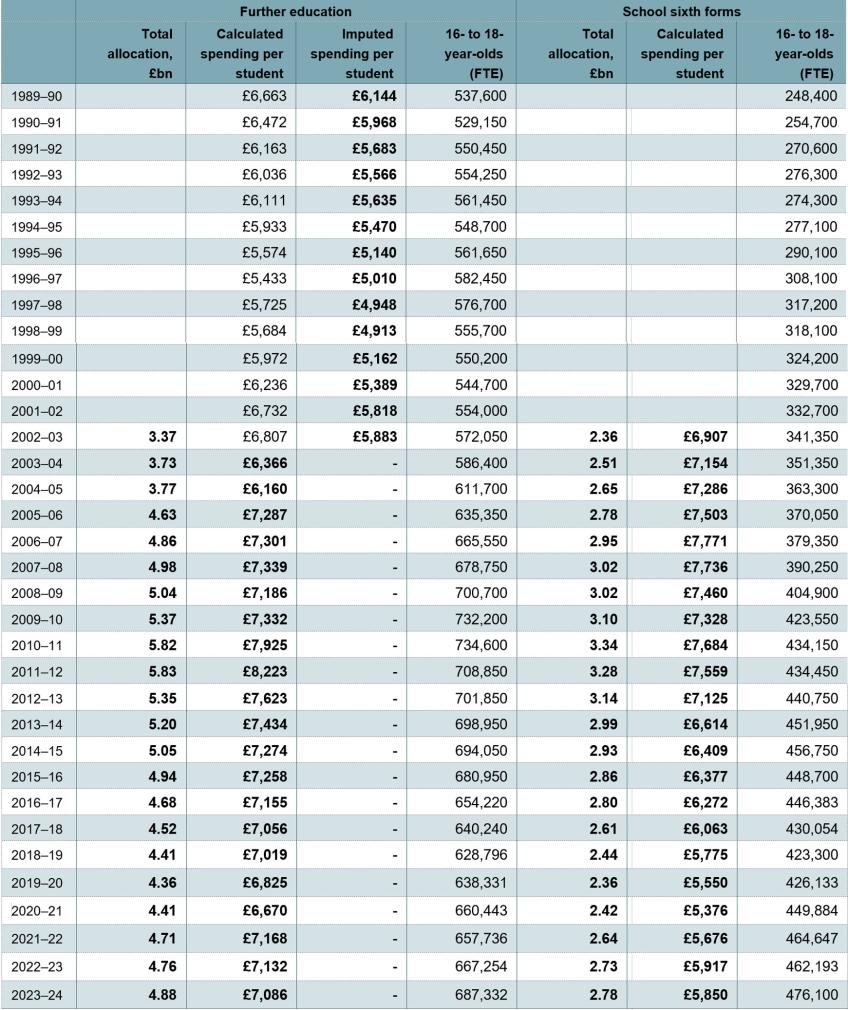

Here we detail how we constructed our series for spending per student in further education colleges (including sixth-form colleges) and school sixth forms (academies and maintained schools). Table 1 gives details of the numbers and sources.

2003–04 to 2023–24

From 2003–04 to 2023–24, we are able to calculate both sets of figures by first calculating total reported allocations to further education and sixth-form colleges and to school sixth forms. This includes spending on learners with learning difficulties or disabilities between 2005–06 and 2014–15 (no spending is reported outside of these years) and high-needs top-up payments from local authorities to 16–18 providers between 2013–14 and 2023–24. For colleges, we are able to calculate these directly as top-up payments to post-school providers. For school sixth forms, we impute them as 0.125 of the total top-up payments to state-funded secondary schools (0.125 being the approximate share of pupils at state-funded secondary schools who are aged 16–19).

For years between 2003–04 and 2015–16, we can then simply divide these allocations by the reported numbers of students by institution type. This includes pupils aged 16–18 who are participating in further education at higher education institutions.

From 2017, sixth-form colleges had the opportunity to convert to academy status. This creates a problem for our analysis as the funding shifts from being classified at 16–18 colleges towards academies with school sixth forms. The students also move from being classified as in sixth-form colleges towards academies. Unfortunately, the student and funding data are reported at different times of the years and are highly likely to be inconsistent with one another. Using the raw data would lead to a misleading conclusion. We therefore employ the following steps from 2016–17:

- We manually recode academy sixth-form colleges back to sixth-form colleges. There are fewer than 20 of these in academic year 2017–18, though closer to 30 by 2023–24.

- We calculate total funding (excluding student support and 19+ funding) allocated to school sixth forms and colleges.

- We divide by student numbers at school sixth forms and colleges as reported in national statistics for academic years 2015–16 and 2016–17 (i.e. using end of calendar year 2016 for 2016–17).

- For academic years 2017–18 to 2023–24, we calculate student numbers for school sixth forms and sixth-form colleges in a different way. We first use the national statistics to obtain the total number of students across school sixth forms and sixth-form colleges, and we use the institutional allocations to obtain the percentages of students in school sixth forms and in sixth-form colleges. We multiply the total number of students across school sixth forms and sixth-form colleges by these two shares to get the numbers of students in school sixth forms and in sixth-form colleges. We adjust these figures by the share of part-time students in each institution to get an estimate of the total full-time-equivalent (FTE) numbers. For 2024–25, student numbers are forecast based on Office for National Statistics (ONS) projections for 16- to 18-year-olds in England.

- This gives a series by academic years. We then take averages between years to give a series in financial years (e.g. FY 2017–18 = 4/12 × AY 2016–17 + 8/12 × AY 2017–18).

Before 2004–05

Before 2004–05, figures for spending per student in further education are available from various departmental and ONS publications. These give slightly different levels for spending per student in 2003–04 from the more recent source. We therefore take the more reliable 2003–04 figure and back-cast imputed figures based on past changes in spending per student in further education. Figures for spending per student in school sixth forms are not readily available before 2002–03.

Split by three institutional types from 2013–14 onwards

From 2013–14 onwards, we are able to split spending per student by all three main institutional types: school sixth forms; sixth-form colleges; and further education colleges. These figures are based on reported allocations to providers, with total spending measured as total programme funding for individuals aged 16–18, plus high-needs funding, funding adjustments for young people who have not achieved C grades in English and maths GCSEs, Capacity and Delivery Funding and the Advanced Maths Premium Funding. We adjust student and institution numbers in the same way as above to account for conversions of sixth-form colleges to academy status. However, in contrast to our main figures, we leave these figures in academic rather than financial years, given this is how the data are presented.

We use the same methods and approach to examine how spending per student varies across areas. The only difference is that we use headcounts by institution as recorded within the funding allocations. This is because there are currently no publicly available data on the number of full-time-equivalent students by institution and local authority.

Table 1. Spending on and numbers of students in further education and school sixth forms (spending figures in 2023–24 prices)

Note and source: Number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) students calculated as number of full-time students plus 0.5 times number of part-time students. Spending per student from 2016–17 to 2023–24 calculated based on total funding allocations in annual 16–19 funding allocations (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/16-to-19-education-funding-allocations) divided by the number of FTE students aged 16–18 in further education colleges and school sixth forms. Number of students taken from Department for Education, ‘Participation in education, training and employment: 2022’ (https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/participation-in-education-and-training-and-employment/2022). For 2017–18 to 2023–24, these figures are adjusted based on the number of students reported in the aforementioned 16–19 institutional funding allocations. Spending per student for 2003–04 to 2015–16 calculated as spending on further education for 16- to 19-year-olds, sixth-form spending (maintained schools and academies) and spending on learners with learning difficulties or disabilities as reported in Education Funding Agency annual report and accounts for 2012–13 to 2015–16 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/efa-annual-report-and-accounts-for-the-year-ended-31-march-2016, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/efa-annual-report-and-accounts-for-the-year-ended-31-march-2015, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/efa-annual-report-and-accounts-1-april-2013-to-31-march-2014, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/efa-annual-report-and-financial-statements-for-april-2012-to-march-2013), Young People’s Learning Agency annual report and accounts for 2011–12 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-young-peoples-learning-agencys-annual-report-and-accounts-for-2011-to-2012) and Learning and Skills Council annual report and accounts for 2004–05 to 2009–10 (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-learning-and-skills-councils-annual-report-2009-to-2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-learning-and-skills-councils-annual-report-and-accounts-for-2008-to-2009, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-learning-and-skills-councils-annual-report-and-accounts-for-2007-to-2008, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-learning-and-skills-councils-annual-report-and-accounts-2006-to-2007, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-learning-and-skills-councils-annual-report-and-accounts-for-2005-to-2006, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/learning-and-skills-councils-annual-report-and-accounts-for-2004-to-2005) and divided by number of FTE students aged 16–18 in further education colleges and school sixth forms. Number of students taken from Department for Education, ‘Participation in education, training and employment: 2018’ (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/participation-in-education-training-and-employment-2018). For years between 2013–14 and 2018–19, we also include local authority top-ups for high-needs pupils calculated from local authority spending plans (https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-local-authority-school-finance-data). Figures for spending per student in further education from 1989–90 to 2003–04 taken from Department for Children, Schools and Families departmental report for 2009 (http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/http://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/DCSF-Annual%20Report%202009-BKMK.PDF) and Department for Education and Employment, ‘Education and training expenditure since 1989–90’, Statistical Bulletin 10/99 (http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/13586/1/Education_and_training_expenditure_since_1989-90_%28Statistics_Bulletin_10_99%29.pdf). Imputed figures are calculated by back-rating the calculated figure in 2003–04 by the real-terms growth in the calculated series (figures for overlapping years are not shown here). HM Treasury GDP deflators, November 2023 (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp-november-2023-autumn-statement).

Student numbers

For reasons of historical consistency, we report the number of full-time England-domiciled students studying at designated providers in England. For all cohorts for which Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) data are available, we report those figures (from SB262 figure 9). A ‘nowcast’ for the latest data is obtained using official forecasts for student entrants by the Department for Education (from table 2.1 of Student entrants model), assuming a three-year degree length, a constant share of English-domiciled students studying in England, a constant share of entrants in the designated approved provider (approved fee cap) category, and a constant number of entrants in the designated approved provider (approved) category. After the final year of Department for Education (DfE) forecasts, entrant numbers are assumed to be constant as a share of the forecast population aged 18 and 19 based on ONS 2020-based population projections. Historical data are taken from Historical statistics on the funding and development of the UK university system, 1920–2002.

Spending per student

These figures measure total resources available to universities rather than long-run public spending per student in order to ensure comparability across education stages. They are presented at the cohort level, because major policy changes in higher education have usually been implemented by cohort (year of entry) rather than calendar year. Estimates for spending per year and student are obtained by dividing an estimate of resources per student by 3 (the average actual degree length observed is roughly three years).

Resources per degree are obtained as the sum of fees and direct teaching grants, minus an estimate of bursaries awarded by universities. Fees are assumed to be charged at the fee cap, which is accurate for virtually all courses. Grants from 2018 onwards are calculated by dividing the total Office for Students (OfS) allocation for high-cost subject funding (from the OfS ‘Guide to funding’, various years) by an estimate of the number of full-time English-domiciled students studying at designated providers in England (constructed as described above). Grants in previous years were calculated using a ‘bottom-up’ approach based on each student’s eligibility for grant funding (this was preferable in the mid 2010s as, due to the 2012 reforms, different cohorts attending university at the same time attracted very different levels of teaching grants). Other OfS funding including ‘targeted allocations’ is excluded.

Student loan model

Many of our calculations regarding student loans make use of the IFS student finance calculator, which draws on the IFS model of student loans and graduate earnings. The calculator applies to England-domiciled full-time undergraduate students at higher education institutions and designated alternative providers in the ‘approved fee cap’ category (but not further education colleges). The model is based on the simulated lifetime earnings profiles of 20,000 representative graduates.

Duration of study and rates studying in London for men and women were taken from HESA data. The distribution of parental income is taken from the Family Resources Survey (FRS). The parameters of the simulation model were estimated using data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and the British Household Panel Survey / Understanding Society. Forecasts for average earnings and various inflation measures are taken from the Office for Budget Responsibility’s November 2023 Economic and Fiscal Outlook (except for the long-term forecast, which reflects the Office for Budget Responsibility's Long-term economic determinants - March 2023.

Assumptions of the student loan model include:

• all borrowers take out the full tuition fee loans to which they are entitled;

• there is 95% take-up of maintenance support, to match Student Loans Company figures on take-up in recent years;

• borrowers do not repay their loans early by making voluntary contributions;

• the parameters of the student loans system do not affect graduates’ gross earnings.