Corporation tax explained

Corporation tax is the fourth biggest source of revenue for the UK Treasury and is forecast to raise around £40 billion in 2021–22.

It is levied on the profits of companies operating in the UK (the profits of unincorporated businesses – sole traders and partnerships – are subject to income tax rather than corporation tax). Companies operating in more than one country are, broadly speaking, taxed on the profits that are deemed to have arisen from UK-based assets and production activities. Different rates of corporation tax have, at various times, been applied to banking, North Sea oil and gas production, companies with small profits, and profits earned from patented technologies. The evolution of these rates is shown in the chart below.

Taxable profits

In broad terms, profit is revenue minus costs.

Corporation tax is charged on income from trading (i.e. from the sale of goods and services) and investments, minus day-to-day expenses (known as ‘current’ or ‘revenue’ expenditure, which includes wages, raw materials and interest payments on borrowing) and various other deductions, notably allowances for investment costs. It is also charged on capital (‘chargeable’) gains, the profit from selling an asset for more than it cost. If a company makes a loss – its costs exceed its revenue – it can, subject to restrictions, set the loss against profits it makes in other years.

While ordinarily current expenditure is deductible, research and development (R&D) tax reliefs allow companies to deduct more than 100% of qualifying current expenditure on R&D. R&D tax reliefs are more generous for small and medium-sized companies than for large companies.

Unlike current expenditure, investment (or capital) spending on things such as machinery and buildings is not automatically deductible when calculating taxable profits. Instead, capital allowances can be used by companies to deduct their capital expenditure from taxable profits over a number of years.

Capital allowances come in a number of forms that differ in their structure and generosity. In practice, most small and medium-sized companies can deduct most of their investment spending immediately under the annual investment allowance (AIA). Companies can even deduct more than the full cost of some investment – a so-called ‘super-deduction’ – for the two years from 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2023, a policy closely linked to the announcement that the main rate of corporation tax will increase from 19% to 25% in April 2023.

If a company sells an asset, it is taxed on any capital gain (the rise in the value of the asset since it was acquired, i.e. the proceeds of sale minus the original purchase cost). If capital allowances have been claimed for the asset, a ‘balancing adjustment’ is made to ensure that the capital gain/loss, the capital allowances and the balancing adjustment together equal the overall change in the value of the asset. So, for example, if the purchase cost of an asset has already been fully deducted through capital allowances (under the AIA, for example) then the full proceeds of sale are taxed, not just the capital gain: the purchase cost is not deducted a second time when the asset is sold.

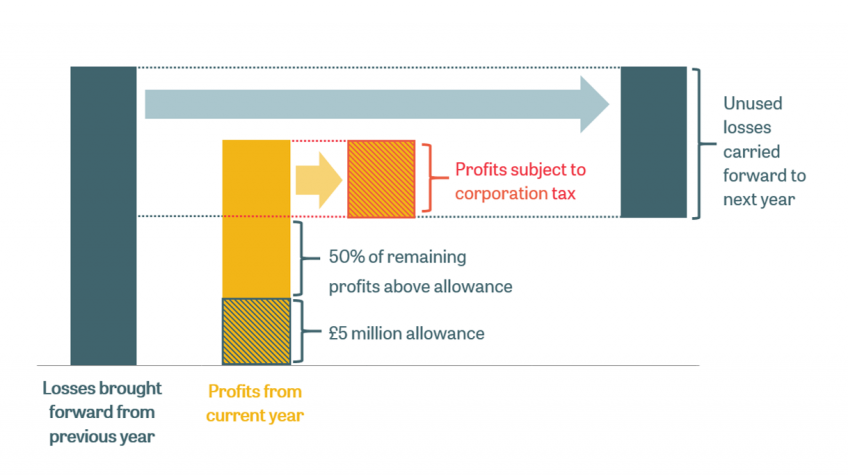

If a company makes a loss in a given year, it cannot claim a tax refund, but it can offset the loss against profits it makes in other years, subject to various restrictions. Losses can usually be carried back by only one year (temporarily extended to three years in the wake of COVID-19) or carried forward indefinitely.

Companies are generally taxed on the profits they make over the 12 months for which they draw up their company accounts (though it can differ in some cases, notably in the first and last years of business). Most companies choose to start their accounting years in April, matching the tax year. But if a company’s accounting year straddles two tax years (e.g. it produces its accounts on a calendar-year basis) and the tax rate changes, then its profits for the accounting year are in effect taxed at a weighted average of the two tax rates according to the number of days in the accounting period before and after the tax rate change. Large companies are required to pay corporation tax in four equal instalments on the basis of their anticipated liabilities for the accounting year. Small and medium-sized companies pay their total tax bill nine months after the end of the accounting year.

Corporation tax rates

In 2021–22, the main corporation tax rate is 19%. A reduced rate of 10% applies to profits relating to patented technologies, a policy known as the ‘patent box’. Higher rates apply to banks and to North Sea oil and gas production; we discuss these in the following sections.

The chart above shows that the main rate of corporation tax has fallen substantially over the last four decades, from 52% in the 1970s to 19% now. The March 2021 Budget announced that in April 2023 the main rate of corporation tax will rise to 25% – that would be the first rise in the main rate of corporation tax for half a century.

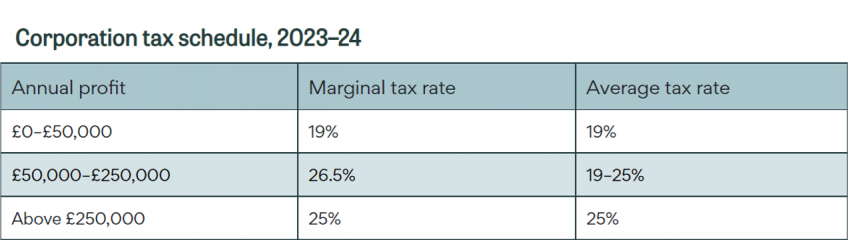

This rate increase will not apply to all companies, however. For companies with profits below £50,000, the rate will stay at 19% and become the ‘small profits rate’. And for companies with profits between £50,000 and £250,000 a system of ‘marginal relief’ will operate, such that an effective marginal tax rateThe amount of additional tax due as a percentage of each additional £1 of a tax base (such as income).Read more of 26.5% applies on profits in excess of £50,000. This acts to increase the average tax rateThe amount of tax paid as a percentage of the tax base (typically income).Read more gradually until it reaches 25% (see chart and table below). Only companies with profits above £250,000 will face the 25% main rate of tax. Operating a small profits rate and a marginal relief system adds unnecessary complexity, creates unnecessary economic distortions (why have a stronger disincentive to increase profits between £50,000 and £250,000 than above or below that range?), and cannot be justified on distributional grounds: companies with low profits are not akin to people with low incomes.

Corporation tax had a small profits rate in the past, until it was abolished in April 2015 (see chart above). However, it applied up to a much higher profit threshold: for the twenty years prior to its abolition, the small profits rate applied to profits up to £300,000, with marginal relief between £300,000 and £1,500,000 (the thresholds were lower before 1994).

Legislation passed in 2015 put in place the legal apparatus to devolve corporation tax rate-setting powers to Northern Ireland. The UK government committed to provide the Northern Ireland Assembly with these rate-setting powers once its finances are on a ‘sustainable footing’. In November 2015, the Northern Ireland Executive stated an intention to reduce the rate to 12.5% for most trading profits from April 2018 (in line with the rate in the Republic of Ireland), but so far the power to do so has not actually been devolved. The process was complicated by the collapse of the Northern Ireland Executive in 2017 and other political developments, but since the restoration of power-sharing in 2020 there seems to have been little impetus to implement the devolution of corporation tax.

Taxation of banks

Since April 2016, banks and building societies have been subject to an 8% surcharge levied on the same base of taxable profits as corporation tax. The first £25 million of a bank’s taxable profits are exempt from the surcharge.

The March 2021 Budget announced that the bank surcharge will be reviewed so that, when the main rate of corporation tax increases from 19% to 25% in 2023, ‘the combined rate of tax on the United Kingdom banking sector doesn’t increase significantly from its current level’. This appears to imply a reduction in the bank surcharge; the government said it will set out its plans in the autumn.

In addition, since January 2011, banks are subject to the bank levy. Unlike corporation tax, the bank levy is not a tax on profits. It is an annual charge on certain balance-sheet liabilities and equity of banks and building societies, such as certain customer deposits.

Taxation of North Sea oil and gas

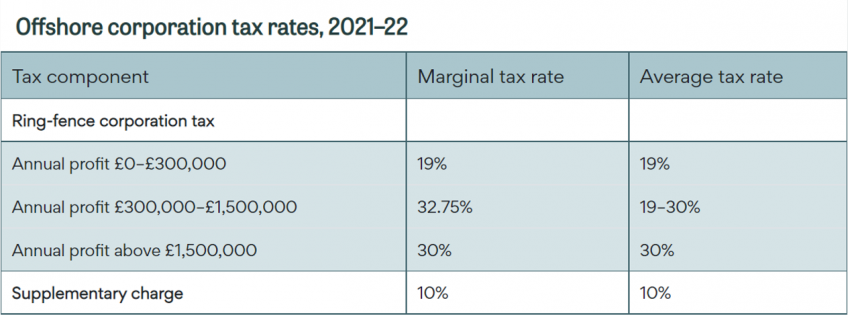

The tax regime applied to profits derived from North Sea oil and gas production differs in a number of ways from that applied to onshore profits. Overall rates are substantially higher (as shown in the chart at the start of this article) and there is a more generous system of capital allowances.

The charts below show the evolution of revenue derived from the taxation of North Sea oil and gas since the introduction of the, now defunct, petroleum royalty in 1968–69. Revenue derived from North Sea production peaked in 1984–85 at just over 3% of GDPGross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of an economy’s size. It is the monetary value of all market production in a particular area (usually a country) in a given period (usually a year).Read more, comprising more than 10% of total tax revenue in that year. It then declined precipitously and, after rising somewhat during the 1990s and 2000s, declined again after 2011–12 and has been close to zero since 2015–16. Much of the variation reflects changes in oil prices, but the decline since the 1980s also reflects a combination of a reduction in tax rates, declining output and, since at least 2008–09, increased levels of tax-deductible expenditure.

Taxation of multinationals

Where companies operate in more than one country, it is necessary to determine what profits should be taxed in the UK. Broadly speaking, the international consensus is that profits should be taxed in the country where underlying value is created (this is known as a ‘source-based’ corporation tax). As such, companies are, broadly speaking, taxed on the profits that are deemed to arise from their UK-based assets and production activities. The returns to intangible assets, which do not have a physical location – e.g. patented technologies – tend to be taxed where the owner of the asset is located, which can be different from the location where the asset was originally created.

One implication of the source-based way we choose to tax corporate profit is that UK taxable profit is distinct from, albeit often related to, profit arising from sales to UK customers, some of which will be attributable to assets and activities outside the UK.

To see how corporation tax treats international activity, consider the following simple example. A French company manufactures cars. Some of the parts for the cars are imported from other countries and the car is based on designs created in Switzerland. The cars are all imported into the UK and sold by a UK car dealership. Assuming all of the companies involved are unrelated, the UK company will have to buy the cars from (and therefore make a payment to) the French company, and the French company will have to pay companies in other countries for the imported parts and the Swiss designs. In this case, although all of the revenue from selling cars initially arises in the UK, part – and possibly most – of it will flow to (and be taxed in) other countries. The profit that is taxed in each country will be determined by the market prices for the various goods and services. If, say, consumers buy the cars mainly because they like the design, the Swiss company will be able to charge a high price and much of the profit will end up in Switzerland.

The situation is much more complicated when companies operating in different countries are owned by the same multinational parent company. In such a case, there are no market transactions between different parts of the same company and income will not necessarily flow to the country where the underlying activity took place. To assess where profit should be taxed in such cases, different parts of a multinational company are effectively required to ‘buy’ and ‘sell’ goods and services from each other. This is achieved through the operation of ‘transfer pricing’, where the ‘transfer price’ of a transaction that happens within a multinational company is required to be set in line with the ‘arm’s length principle’: that is, set as if the transaction were happening between entirely unrelated companies. This can be thought of as trying to replicate the allocation of profits that would occur if all the companies were separate (as in the initial example above). It can, however, be very difficult to estimate transfer prices. Often the question of the appropriate price for an intra-company transaction, and therefore how much profit is attributable to the activities in one specific country, does not have a single ‘right answer’ even in principle, let alone an objectively measurable and verifiable one.

The rules that surround transfer pricing are complex. Such rules are needed in a source-based corporation tax because companies have an incentive to arrange and report their activities in such a way as to reduce their tax liabilities by shifting their profits to lower-tax countries. But there remains significant scope for profit-shifting because of the difficulty of determining appropriate transfer prices, especially when companies have more information than governments.

Manipulating transfer prices is only one way in which multinationals may seek to locate their profits in low-tax countries under a source-based tax system: there are many others. In broad terms, they all involve allocating costs to (and therefore reducing taxable profits in) high-tax countries, while allocating revenues to low-tax countries. This could be achieved by, for example, locating intellectual property in a low-tax country (and making royalty payments for its use in a high-tax country) or making a loan from a subsidiary in a low-tax country (where the interest payments received will be taxable income) to one in a high-tax country (where interest payments made will be tax-deductible).

Over the past decade, the OECDThe Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international body representing 38 mostly rich countries.Read more has been leading on international efforts to change international tax rules and treaties in ways that help to reduce ‘base erosion and profit shifting’. There is widespread agreement on the need for reform and some progress has been made, but talks are ongoing and reaching international agreement on the specifics is difficult.

In the UK, successive governments have implemented specific new measures aimed at reducing tax avoidanceThe use of lawful means to pay less tax, particularly where contrary to the clear intention of parliament.Read more by multinational companies, including:

- a cap on the amount of interest payments (relative to its UK profits and its worldwide interest payments) a company can deduct when calculating its taxable profits;

- a new diverted profits tax on profits that are deemed to have been diverted away from the UK as a result of artificial arrangements;

- a new digital services tax on the revenues (rather than profits) of search engines, social media services and online marketplaces that are deemed to generate large revenues from UK users.

Corporation tax revenue and who pays

The chart below shows corporation tax revenue over time. Revenue is volatile because profits vary strongly with the economic cycle. Despite the long-term downward trend in the main rate of corporation tax, corporation tax revenue has not declined as a share of GDPGross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of an economy’s size. It is the monetary value of all market production in a particular area (usually a country) in a given period (usually a year).Read more – it has remained broadly in the range of 2–3% of GDPGross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of an economy’s size. It is the monetary value of all market production in a particular area (usually a country) in a given period (usually a year).Read more for much of the last half-century. This is because the corporate tax base has grown faster than GDPGross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of an economy’s size. It is the monetary value of all market production in a particular area (usually a country) in a given period (usually a year).Read more. This reflects partly an increase in corporate profitability and partly policy changes to broaden the definition of profits subject to tax.

Corporation tax revenues are highly skewed: most revenue is raised from a small number of companies making very large profits. In 2018–19, 55% of all corporation tax was paid by companies that made a tax payment of £1 million or more: a group of fewer than 5,000 companies, making up just 0.3% of the population of corporation-tax-paying businesses. This is shown in the chart below.

Corporation tax revenue also relies heavily on certain industries. Financial services in particular play an outsized role in contributing corporation tax revenue: the industry accounts for around 7% of the UK’s economic output but around 22% of corporation tax revenue (see chart below).

Characterising the companies that pay corporation tax is relatively straightforward. Much less straightforward is translating this into a picture of the economic incidenceThe economic incidence of a tax describes which people are ultimately made worse off by the tax (and can be different from those who are legally liable to pay the tax).Read more of the tax: which individuals ultimately bear the burden, in the sense of having their living standards reduced by the tax.

The direct effect of corporation tax is to reduce companies’ after-tax profits and therefore the return to company shareholders (e.g. through lower dividends). This will affect not only individuals with direct shareholdings but also those who hold shares indirectly via private pensions or investment funds. In so far as shareholders bear the burden of corporation tax, a significant portion of it will fall on individuals based overseas (just over half of all shares listed on the London Stock Exchange are owned outside the UK). (Conversely, people in the UK who own shares in foreign companies will bear some of the burden of other countries’ corporation taxes.)

However, economic theory and evidence strongly suggest that the incidenceThe economic incidence of a tax describes which people are ultimately made worse off by the tax (and can be different from those who are legally liable to pay the tax).Read more of corporation tax is not exclusively on shareholders. In some cases, companies will set higher prices, or pay lower wages, than they would in the absence of corporation tax, such that part of the burden of the tax will be felt by customers or workers respectively. Evidence shows that corporation tax affects how much companies invest and where they locate their real activities. To the extent that companies respond to corporation tax by doing less investment in the UK, a lower capital stock and associated lower productivity will leave UK employees with lower average wages.