Summary

The value of government support for living costs for university students from the poorest families will fall to its lowest level in seven years in the coming academic year, as maintenance loan entitlements will fail to keep up with inflation. As a result, even students entitled to maximum maintenance loans will have to make do with substantially less than they would earn working in a minimum wage job.

These cuts in support are entirely due to forecast errors: annual increases in maintenance loans are based on inflation forecasts made years in advance, and inflation has recently been much higher than originally forecast. Students from the poorest families will lose £100 per month compared with what support would have been had the forecasts been correct.

Commentary

In England, government support for living costs for university students is almost entirely provided in the form of so-called maintenance loans. All England-domiciled students are eligible for these loans; the amount they can borrow depends on their families’ household income, whether they live at home during term time, and whether they are studying in London. These maintenance loans are added to any loans for tuition fees and repayable after graduation, but most students are unlikely to pay off their loans in full before they are written off at the end of the 30-year repayment period (with no adverse consequences for graduates).

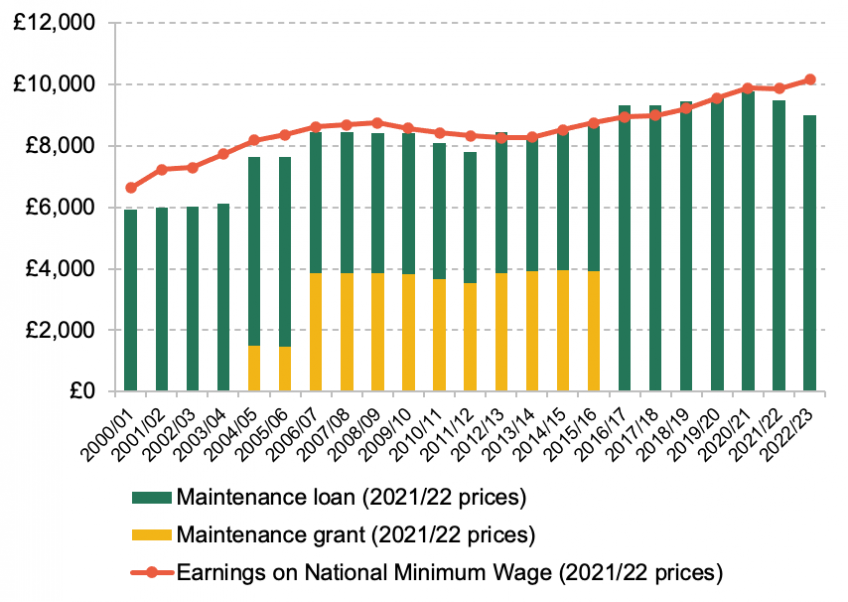

Students from the poorest families living away from home during term time and studying outside London will be able to borrow £9,706 in the 2022/23 academic year. In real terms, this will be the lowest level in seven years; before 2016/17, total support was lower, but a substantial proportion of it was provided in the form of grants instead of loans (see Figure 1). At only 2.3%, the cash-terms increase in entitlements this year will fall far short of CPI inflation, which is set to be around 8% over the relevant period.[1] This will add to a similar shortfall for the current academic year, when the uplift was 3.1% compared with CPI inflation of more than 6%. For the first time since 2003/04, the maximum maintenance loan entitlement will also fall more than £1,000 short of what a 22-year-old student would earn if they worked in a job that paid the National Minimum Wage instead of studying.

Figure 1. Maximum maintenance support (loans and grants) compared with earnings on the minimum wage (2021/22 prices)

Note: All monetary amounts are in CPI real terms. In order to align with government calculations, the price level for an academic year is taken to be the price level in the first calendar quarter falling into that academic year. In each academic year, the chart reflects the maintenance system as it applied to new students.

For minimum wage calculations, the academic year is taken to run from the start of October to the end of September, and the minimum wage at age 22 is used. Following the Augar Review, earnings on the minimum wage are calculated by multiplying the hourly minimum wage by the expected study time for a full-time undergraduate (37.5 hours per week over 30 weeks).

Source: House of Commons Library; Low PayCommission; author’s calculations.

Real-terms cuts in maintenance loans are not supposed to happen. According to stated policy, the government aims to ‘ensure that students do not suffer a real reduction in their income’. In fact, the annual cash-terms increase in maintenance entitlements is meant to reflect the change in the Retail Prices Index excluding mortgage interest (RPIX), a measure of inflation with a well-documented upward bias, so maintenance entitlements should typically be going up by more than actual inflation measured by the change in the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). This is indeed what happened between the last major reform of the system in 2016/17 and the 2020/21 academic year: every year, maintenance entitlements rose slightly in real terms. So why are they falling now?

The reason is that rather than being based on actual RPIX inflation, annual increases in maintenance entitlements are based on RPIX inflation as predicted by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) years in advance. For example, the increase of 2.3% for the 2022/23 academic year was taken from the November 2020 OBR projections. But these projections are now woefully out of date, because inflation has been much higher than forecast then. If the government used the most recent March 2022 OBR projections, the increase would be 9.2%, as predicted RPIX inflation for 2022/23 is now much higher. The same happened with the increase for the current academic year: because inflation was higher than initially forecast, increases in maintenance entitlements fell far short of both CPI and RPIX inflation.

The cuts arising from these forecast errors are large. For the poorest students, the loan entitlement would already be £9,980 in the current academic year had the forecast for RPIX inflation between 2020/21 and 2021/22 been correct, and would be £10,860 in the next academic year if the uplift was in line with the latest OBR forecast for RPIX inflation. This means that merely because of forecast errors, students from the poorest families will be £1,200 out of pocket in the next academic year, or around £100 per month.[2]

Remarkably, there is no mechanism in place for these errors ever to be corrected. Below-inflation increases in 2021/22 and 2022/23 will never be made up with above-inflation increases later on. As a result, the current maintenance loan cuts will in principle remain in place forever – unless and until policy changes.

Adding to these stealth cuts in the level of maintenance entitlements is a freeze in the parental earnings thresholds that govern eligibility for means-tested maintenance support. The lower parental earnings threshold, below which students are eligible for the maximum maintenance loan, has been frozen in nominal terms at £25,000 since 2008 (had it been indexed to average earnings, it would now be around £35,000). But its effect will be particularly painful in times of high inflation: many students’ parents will see their income rise in cash terms but fall in real terms. As a result, many students will be eligible for smaller maintenance loans, even though their parents will be less able to support them.

The government should urgently review how maintenance entitlements are determined. While reasonable people can disagree on the appropriate level of living cost support for university students, it makes no sense for it to be determined by errors in inflation forecasts. A simple fix would be to use more recent forecasts and correct remaining errors when actual values are known in the following year.[3]Freezing parental earnings thresholds in nominal terms is not sensible, either; they should be indexed either to inflation or to a measure of earnings growth.

Notably, the government already has a blueprint for a better maintenance system at its disposal: its own Augar Review of post-18 education, published in 2019, made a number of sensible suggestions for a reform of the maintenance system. These included the reintroduction of maintenance grants to replace part of means-tested maintenance support; tying the maximum rate of maintenance support directly to earnings on the National Minimum Wage for 21- to 24-year-olds; and indexing parental earnings thresholds for maintenance support to inflation. Regrettably, the government chose to ignore all of these recommendations in its response to the Augar Review earlier this year. It is high time that it took another look.

Endnotes

[1] In order to align with government calculations, the price level for an academic year is taken to be the price level in the first calendar quarter falling into that academic year.

[2] This calculation is based on students spreading their maintenance loans across a whole year (12 months). In practice, many students rely on other sources of funding outside of term time, so the monthly cut in pound terms during term time will typically be even larger.

[3] It is understandable that regulations need to be laid in good time before the start of the academic year. But the regulations for 2022/23 were laid before Parliament in December 2021, when the OBR had already produced two more recent sets of forecasts than the November 2020 forecasts that were used.