The Palace of Westminster has seen better days. Wayward masonry falls with ever greater regularity, forgotten corridors moulder, and decades’ worth of antiquated wiring threatens to at any moment burst into flame. It is hard to imagine a more appropriate building for the UK’s tax system to have been devised in.

From council tax to National Insurance, from VAT to environmental levies there are few corners of the British tax system that are not in urgent need of repair. With what is likely to be an election year on the horizon now is the time to look beneath the floorboards of that ramshackle structure and take stock of some of the horrors that lie beneath.

A good place to start is housing taxation. Alarmingly, council tax (which raises the considerable sum of £44 billion a year) is still based on property values as they were in 1991 – an era when a terraced house in Islington would cost you around £90,000 (you can expect to pay £1.1 million today). That means council tax bands have become increasingly arbitrary, often bearing little relation to the present value of housing.

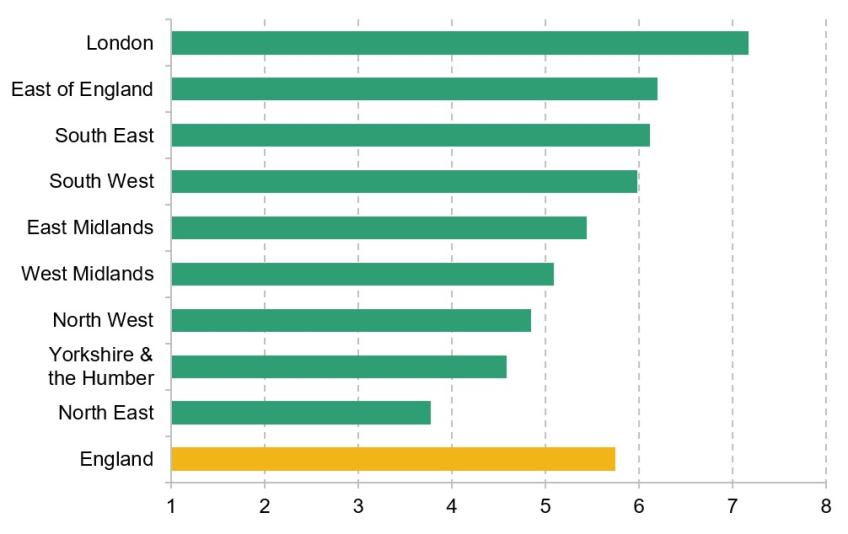

As Figure 1 shows, house prices have grown at very different rates in different parts of the country. In conjunction with the mechanism for allocating funding to local councils, outdated valuations mean that regions where property values have grown most strongly since 1991 (like London and the South East) are treated increasingly favourably when it comes to council tax compared to those where they have grown more slowly (like the Midlands and the North).

Figure 1. Average property price in April 2023 as a multiple of January 1995, by region

Source: Figure 11 in Delestre, I. & Miller, H., ‘Tax and public finances: the fundamentals’. IFS.

The best that can be said for council tax is that, were it to be seriously reformed, there would at least be a case for its continued existence. Stamp duty, on the other hand, deserves no similar praise. Taxing housing transactions means that those who move house more often pay more tax (not something that adheres to any obvious principle of fairness). The result is to throw an almighty spanner into the gears of the housing market. Everything from downsizing in retirement (freeing up unused housing) to moving house to find a better job is discouraged. A tax that does so much damage is beyond repair. It should be abolished entirely.

So much for housing taxation, what about personal taxes? Income tax and National Insurance are, at least, not levied on people’s incomes as they were in the early 1990s. That, however, is about as far as praise can extend. The first question to ask is why National Insurance contributions (NICS), which are the UK’s second largest revenue raiser after income tax, exist at all. While it was once the case that NICs played a significant role in determining benefit entitlements, this relationship has been eroded almost to the point of non-existence. In effect the UK now simply has two separate income taxes.

That inheritance is a damaging one. For a start, NICs is levied only on earnings from employment and (at lower rates) self-employment. Other forms of income (like dividends or rent) incur no liability. Then there are employer contributions, which are charged on the wages paid out to employees but for which no equivalent exists for the self-employed. One consequence of that is to create a tax system in which employment is heavily penalised.

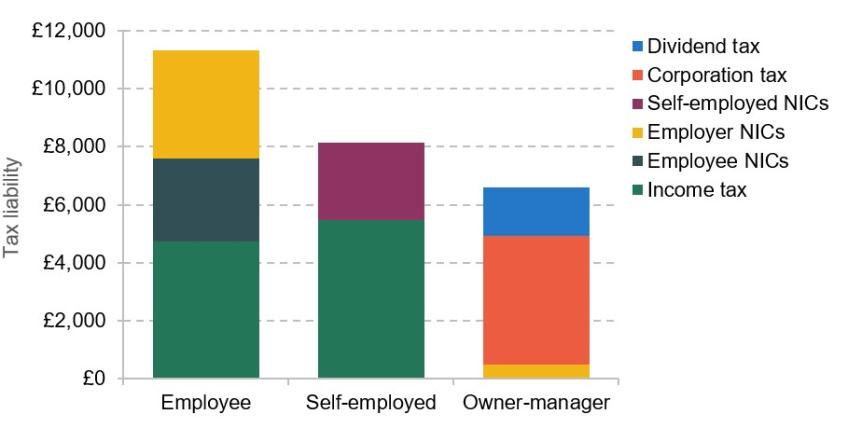

Figure 2 sets out these tax differences explicitly for an example person generating £40,000 of income per year. If our example person is an employee then the total tax liability incurred will be a little over £11,300. As a self-employed sole-trader or partner, on the other hand, that tax bill would be just over £8,100. This more than £3,000 gap is almost entirely a result of employer NICs.

Figure 2. Tax due on a job generating £40,000 in 2023–24

Note: Employees are charged income tax on income excluding employer NICs (this is why income tax is slightly higher for the self-employed than for employees – the self-employed receive more of the £40,000 as taxable income). Excludes trading allowance and employment allowance where applicable. We assume no pension contributions are made.

Source: Figure 6 in Delestre, I. & Miller, H., ‘Tax and public finances: the fundamentals’. IFS.

That gap gets wider still if we imagine our example earner operating through an owner-managed company, allowing them to pay just £6,600 in tax. That’s because owner-managers have the option of paying themselves a £12,570 salary (small enough that no income tax is incurred) and taking the remainder of their £40,000 in the form of a dividend. While corporation tax will need to be paid on the profits from which the dividend is paid, this is more than made up for by lower income tax rates on dividend income and (crucially) the fact that no NICs at all is due on dividends.

While it’s true that the self-employed enjoy somewhat less generous benefit entitlements than employees, these differences are far too small to account for the large disparity in tax treatment. By driving a wedge between the tax liability of employees and the self-employed, NICs therefore generate serious biases in the labour market. Self-employed contractors (for example) become relatively more attractive to employ, while partnerships can be disincentivised from incorporating.

A better aligned set of tax rates across all legal forms would be a welcome development. Better still, income tax and NICs could be combined into a single, unified tax on income – a reform that would leave the tax system both more rational and less opaque.

After Income tax and NICs, the UK’s next largest tax is VAT. Here, surely, we are on firmer foundations? The darling of many economists, VAT has been described as “perhaps the most economically efficient way in which countries can raise significant tax revenues”. And yet look behind the wallpaper and you will find that the UK’s VAT is riddled with cracks.

A key problem is that many goods and services are not subject to the main 20% rate. A reduced 5% rate applies to domestic energy and a few other products, and a zero rate applies to large swathes of goods ranging from new housing to children’s clothing to (most) food.

At first glance many of these reduced rates sound like reasonable measures. After all, poorer households tend to spend a larger share of their budget on zero or reduced rate items like food and utility bills, meaning that they reap the greatest benefit (relative to their overall level of spending).

But if the intention of reduced rates is to help struggling households it is a fantastically expensive way of achieving that goal. In cash terms better off households spend far more on reduced-rate items than poorer households (even if they make up a smaller share of those households’ budgets). The result is that reduced and zero rates cost the Treasury £64 billion in foregone revenue in 2022-23 (more than total spending on Universal Credit in the same year). In other words, it would be perfectly feasible to remove VAT reduced-rates, compensate low-income households through higher welfare payments and raise still raise significant amounts of revenue.

But VAT reductions aren’t just poorly targeted at helping those on low incomes. They also do active economic damage. When parliament designates a particular class of goods as zero-rated, this brings with it the need to police the boundary between which products qualify for zero-rating and which don’t. Such rules rapidly descend into pantomime. A gingerbread man with two chocolate eyes? Zero rated. Add chocolate smile? That will be 20% VAT. Thinking of buying a pet puppy? 20%. What about a rabbit instead? You’re in luck, they’re zero rated (thanks to the fact they are edible).

Any tax system that leads to thousands of hours and millions of pounds being spent on legal disputes over whether Jaffa Cakes really are cakes (zero rated) rather than chocolate covered biscuits (20% rated) is one that urgently needs reform. Each year that the current system stays in place means more time, money and ingenuity wasted on such ludicrous disputes.

One of the newer conurbations of UK tax legislation is made up of the various environmental levies and taxes created in response to the challenge of climate change. Unfortunately, the lack of a good architect is already showing. Overlapping, and at times contradictory, policies have created a complex, piecemeal structure that generates inconsistent incentives to reduce emissions.

Fundamentally, the problem of climate change is that those undertaking greenhouse-gas-emitting activities do not face the full costs that their actions impose on society. To a first approximation, the simplest remedy to that is a tax on carbon. To be most efficient, a tonne of CO2 should be taxed at the same rate no matter where, or by whom, it is emitted. That avoids a situation where a sector or individual makes expensive emissions reductions that could have been made more cheaply elsewhere – minimising the total cost of decarbonisation.

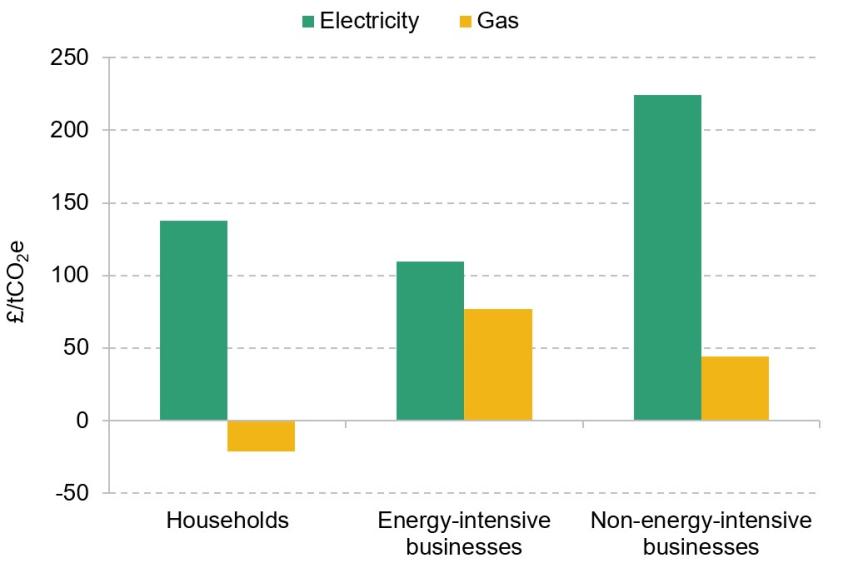

While there are a range of policies that implicitly or explicitly tax carbon, they are poorly coordinated, meaning that different people often face wildly different carbon ‘prices’. Figure 3 shows this explicitly; setting out the combined effect of the no fewer than nine different policies that implicitly tax carbon in the energy market. The result is confusion. For businesses operating in non-energy-intensive sectors, for example, the implicit tax rate on electricity is £224 per tonne of CO2 emitted but just £44 per tonne for gas. Emissions associated with household gas consumption, meanwhile, are actually subsidised relative to other forms of consumption thanks to the reduced 5% rate of VAT levied on household energy bills.

Figure 3. Implicit tax rates on emissions in the energy market, 2023–24

Note: Figures for electricity refer to electricity generated from the burning of natural gas. Implicit taxes encompass charges made as a result of the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), carbon price support, the climate change levy, contracts-for-difference, the Renewables Obligation, feed-in tariffs, the warm home discount and the Energy Company Obligation. Allocations of free ETS permits are ignored. An implicit tax of zero is taken to include the standard VAT rate of 20%. Additional VAT paid as a result of levies’ increasing retail prices is included in the final implicit tax/subsidy figure. ‘Energy-intensive businesses’ excludes electricity generators. The effects of the energy price guarantee are ignored for the purposes of this analysis.

Source: Figure 14 in Delestre, I. & Miller, H., ‘Tax and public finances: the fundamentals’. IFS.

And that is just the energy market. All across the economy – from motoring to aviation – current policy is producing hopelessly uneven incentives to decarbonise. If action isn’t taken soon, the cost of reaching net-zero (already a formidable challenge) is likely to be greater than it needs to be.

There is much talk in British politics of whether taxes are too high or too low, but far too little about whether they are well designed. At every turn poor design distorts taxpayers’ incentives to work, save and spend; eroding productivity and leaving the nation poorer. Reform will take courage. But if we can find that courage, Britain’s taxpayers will find themselves not only better off but also more fairly treated. Until then, parliament will find that – like the palace in which it sits – delaying repairs will only make them costlier.

This article was first published on taxation.co.uk, and is reproduced here with kind permission.