Brexit has the potential to have a substantial impact on the prices households pay for food. Currently around 30% of the value of food purchased by households in the UK is imported, and the major source of food imports is the EU. In comparison, only 17% of overall consumer spending is on imported goods. This means that changes in the costs of imports – for example, through changes to tariffs or movements in exchange rates – are likely to have a particularly big impact on food prices.

This briefing note discusses how changes in prices of imported food – for example, as a result of changes to tariffs and movements in exchange rates – might affect the prices that different households pay for their overall food baskets.

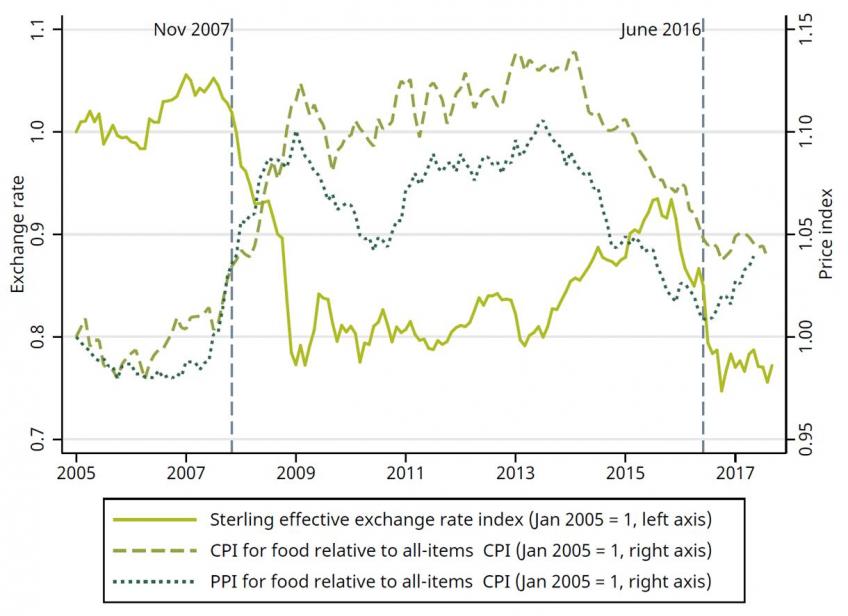

Figure: Exchange rate movements and the real price of food

Key findings | ||

The UK imports a lot of food, with the majority coming from the European Union. |

| Around 30% of food purchased by households in the UK is imported. The major source of total food imports is the EU (which accounts for 70% of gross food imports). This means changes in the costs of imports – for example, through changes to tariffs or movements in exchange rates – are likely to have a big impact on the price consumers pay for food. |

The UK currently benefits from tariff-free trade within the EU. |

| The UK and other EU members currently levy common tariffs on products imported into the EU from other countries. These tariffs are, on average, higher on agricultural products than on non-agricultural products and in some cases considerably higher. There is a lot of variation in tariffs both across and within broad food groups. |

Brexit could potentially have a big impact on the UK’s trade arrangements, not only with the EU itself, but also with other countries with which it currently has trade deals through the EU. |

| If the UK leaves the EU customs union, it would be free to adjust the tariffs it charges on agricultural goods. Under World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, the UK would not be able to set tariffs that discriminate between trading partners, unless as part of a free trade agreement or to give developing countries special access to its market. If the UK and the post-Brexit EU fail to strike a free trade deal, it is likely tariffs would be imposed on EU imports into the UK. This is because the UK would be unable to impose zero tariffs on imports from the EU without also extending tariff-free access to all other WTO members.

|

Exchange rates also affect the price of food. |

| Imports are purchased in foreign currency: when these currencies become more expensive relative to sterling (‘sterling depreciation’), more sterling is needed to purchase the same quantity of foreign currency, and therefore the same quantity of foreign goods. In 2007–08, there was a 21% depreciation in the effective sterling exchange rate; over the same period, there was an 8.7% increase in the price of food relative to other goods. |

It is still too early to tell whether the 13% depreciation in sterling between January 2016 and March 2017 will be associated with similarly sized and persistent effects on food prices. |

| There is, however, evidence that producer prices for food have increased since the referendum. The consumer price for food relative to the overall consumer price level initially declined after the referendum, but started to increase towards the end of 2016. |

Tariff changes and movements in the exchange rate directly affect the cost of getting imported food products onto supermarket shelves. This will feed into the prices faced by consumers for imported goods. The extent to which tariff changes and exchange rate movements feed through to prices is uncertain and may vary across goods. |

| The prices of domestically produced products are also likely to change, for two reasons. First, many domestically produced products use imported inputs, and changes to firms’ costs will tend to feed through to the price they charge for their final product. Second, changes in the price of imported goods are likely to lead to changes in the price of similar domestically produced goods because of competitive effects: for example, if the price of imported goods rises then domestic producers who were competing in the same markets might take advantage of the opportunity to increase their prices too. |

Lower-income households allocate a higher proportion of their spending to food than higher-income households. |

| The lowest-income tenth of households allocate 23% of their spending to food, compared with 10% for the highest-income tenth. Poor households will therefore be more affected by rises in the general level of food prices. |

There is variation in the share of spending on imported products within different food groups. |

| For example, 39% of fruit products are imported, while only 20% of bread and cereal products are imported. However, an additional 12% of spending on bread and cereal products goes on buying products that use imported inputs. |

Variation in the share of spending on different food groups means that different households buy more or less of their food from abroad. |

| There is little variation across income deciles, but considerable variation across households that is not correlated with income or other household characteristics that we observe in the data. |

This variation increases when we look at differences in spending within food groups. |

| On average, households buy around 35% of their beef, lamb and pork from abroad, but some households buy all of it from overseas and others purchase none from abroad. These households are likely to experience different price increases if the costs of imports rise. |