Most European countries experienced a significant increase in government borrowing in the wake of the global financial crisis and Great Recession. Ireland and Spain are well-known for the severe difficulties they faced but France, Italy and the UK also saw borrowing rise sharply. For these countries a combination of the reliance on tax revenues related to the financial sector and asset prices (Ireland, Spain, UK) and/or stickiness in public spending levels, resulted in a large increase in borrowing in the wake of the Great Recession. Examining how these countries responded – in terms of the size, timing and composition of the fiscal measures they resorted to – highlights some interesting similarities but also some notable differences. One common theme, unfortunately, is that these fiscal responses to the crisis largely missed opportunities to improve the overall efficiency of the tax system.

A new special edition of the journal Fiscal Studies examines – for France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom:

- the evolution of GDP, employment and unemployment rates, and the public finances in the run-up to, and through, the financial crisis;

- the scale, timing and nature of the fiscal response; and

- the impact of the reforms on the incomes of different households and on spending on different public services.

Compared with usual cross-country macroeconomic assessments of public finances (for example, by the IMF or the OECD), this special issue relies heavily on the use of micro data and detailed microsimulation models and hence presents a deeper analysis that aims at enhanced comparability between these countries.

The impact of the financial crisis on public borrowing

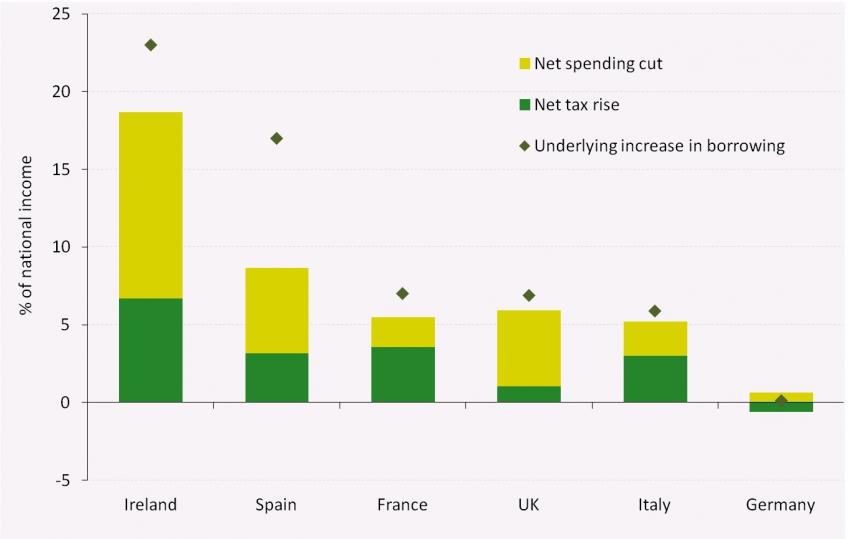

In the years preceding the financial crisis, Ireland and Spain appeared to have the healthiest fiscal positions out of these six countries – having run overall budget surpluses for at least the preceding three years. However, with the onset of the crisis, it quickly became clear that this position was propped up by unsustainable revenues from – in particular – the property market. As the ‘dots’ in the figure show, the financial crisis led to a substantial deterioration in the apparent underlying strength of Ireland’s and Spain’s public finances.

Although suffering a little less severely, France, Italy and the UK also saw their underlying public finances weaken – each by just over 5 per cent of GDP. In other words, had they taken no policy action, they would have ended up borrowing over 5 per cent of GDP more every year forevermore.

The only exception was Germany, whose public finances were – in the long term – unaffected by the Great Recession. Germany was the only one of the six countries for which this looked like a ‘text book’ recession – a temporary increase in borrowing followed by a quick return to normal times.

Size and composition of post-crisis fiscal policy response up to 2014

Notes and sources: See Figure 4 of Bozio, et al. op cit.

Fiscal response

In many ways different countries have taken very different approaches to dealing with the fiscal problems they faced. As the figure shows, France and Italy have both relied relatively heavily on raising taxes, rather than cutting spending, to reduce borrowing. By the end of 2014, two-thirds of the measures implemented in France were aimed at boosting revenue and one-third aimed at reducing spending. Both France and Italy on course to become higher tax, higher spending and high borrowing countries than they were before the crisis hit.

In contrast, the UK has relied heavily on cuts to public spending, rather than net tax rises. Up to the end of 2014–15, 82% of fiscal measures in the UK were spending cuts, rather than net tax rises. The result is that the UK is on course to have a lower level of spending, a similar level of taxation, and a lower level of borrowing than was the case pre-crisis.

Similarities in tax measures but differences on spending

Although each country has relied to rather differing degrees on tax raising measures, the nature of the tax increases implemented across the countries shows some interesting similarities. France, Ireland, Italy, Spain and the UK all chose to increase VAT rates and to increase social insurance contributions. France, Spain and the UK also all implemented income tax rises that were focussed on the highest income individuals, while France the UK both chose to reduce corporation tax rates while widening the base for this tax.

The countries have, however, made rather different choices about which areas of spending to cut. France, Italy and Spain refrained from cutting welfare benefits (and, in fact, increased them for some groups), in stark contrast to Ireland and the UK where cuts to benefit payments for working age adults played a major role in delivering fiscal consolidation. France and the UK have both chosen to afford relative protection to spending on health and education, while Italy and Spain have chosen to cut these services more deeply than other service areas.

Countries have also made different choices about which households should bear the brunt of the consolidation measures implemented so far. In Italy households with children have lost less from tax and benefit reforms than pensioner households; the reverse is true in Ireland and the UK.

“Never let a good crisis go to waste”

With France, Ireland, Italy, Spain and the UK all having planned and implemented large fiscal adjustments since the onset of the Great Recession, we might hope that policymakers would have tried to use this as an opportunity to improve the efficiency of the tax system and public spending in their countries. Or, at the very least, not to have exacerbated existing inefficiencies. Unfortunately, in many cases, the fiscal response to the crisis missed opportunities to improve the overall efficiency of the tax system. To give three examples:

- In France, while the new corporate tax credit (which is computed on individual earnings of firms’ employees) is welcome, it would have been better to have simply reduced the relatively high level of employer social security contributions.

- In Ireland, reforms have unnecessarily created uncertainty and distortions: there has been a succession of VAT changes (increases, reductions and then increases again), while the rate of capital gains tax has since October 2008 been increased from 20 per cent to 22 per cent, then to 25 per cent, then to 30 per cent and then to 33 per cent.

- In the UK, given a relatively narrow VAT base, the increase in the main rate of VAT will have come at the cost of increasing distortions for both producers and consumers; the income tax schedule has also been made considerably more complicated.

With many countries still running deficits in excess of 2 per cent of national income and having a stock of government debt well above its pre-crisis level, this will not be the end of the story. Where there is a need for further spending cuts and/or tax rises, these could be an opportunity for countries to make reforms that improve the efficiency of the tax and benefit system. However, the lesson from the reforms made so far is that we perhaps ought not to be too optimistic on this front and instead may have to be content to settle for reforms that do not add to existing deficiencies.

Carl Emmerson and Gemma Tetlow, Institute for Fiscal Studies.

This observation has been co-published with The Conversation.

![]()

Click here for the full Fiscal Studies introduction.