Research from the US and England shows the central importance of teacher effectiveness in determining pupil attainment. Understanding how to attract high quality teachers to the profession and to particular schools is therefore clearly crucial. In new research released today, we examine salary scales and pupil attainment in primary schools in and around London. For these schools, and for the salary differences of just under 5% that we observe, we do not find evidence that higher salary scales for teachers have much impact on pupil attainment. This suggests that if individual schools offered salary differentials on this scale, they would not necessarily attract more effective teachers.

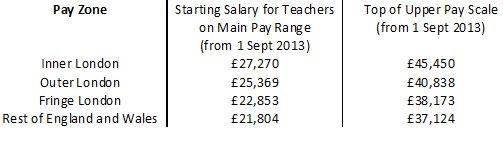

Estimating the impact of teachers’ pay on pupil attainment is complicated as teachers' pay is largely set by national agreements; any variation in salaries tends to reflect the experience of the teacher so it is difficult to separate the impact of teacher pay from teacher experience. In innovative new research, we compare teachers in the same geographical area, with the same levels of experience (on average), who are paid different amounts because of London weighting: teachers in the London area receive higher salaries to compensate them for a higher cost of living (and schools receive extra funding in order to pay for these higher salaries). There are four pay zones in total (inner London, outer London, fringe London and the rest of England and Wales). The current starting salaries for teachers across these zones are shown below, together with the top of the upper pay scale.

We compare pupil attainment in primary schools close to the fringe boundary, where schools are broadly comparable in pupil composition either side of the boundary. As shown above, the salary scales for teachers just inside the London fringe area are just under 5% or around £1,000 higher than they are for teachers at schools just outside.

We find little evidence that these higher teacher salary scales increase pupil attainment in English and maths at the end of primary school. The difference in pupil attainment between schools on either side of the pay boundary is very close to zero for both English and maths. Furthermore, due to the relative precision of our estimates, we are able to rule out even quantitatively small effects (the largest possible effects covered by a 95% confidence interval would be 0.07 and 0.02 standard deviations in English and maths, respectively).

Our work is of course just one piece of evidence. It is based just on primary schools, and the results could be different for secondary schools. But our results are consistent with other research; work from the US (see here also) has suggested that teachers’ decisions about which school to work in are more sensitive to non-pecuniary aspects of the job (such as the mix of pupils at the school and the school environment) than pecuniary ones. Other work for England exploits collective bargaining for teachers to show that a 10% increase in local ‘outside’ wages for teachers (what teachers could earn outside the profession) reduces student test scores at age 16 by about 2%.This suggests that highly effective teachers may be sensitive to pay differentials when they make their initial career choices or when they choose which area of the country to teach in, but the effect is relatively small. Taken together, our respective estimates suggest that the effect of relatively small changes in pay on pupil attainment is either zero or relatively small, and that this seems to apply both to the effect of local wages and salary differentials across schools.

One further important qualification to emphasise is that we are looking at relatively small changes in pay. This doesn’t tell us much about the effect of bigger changes in pay and in particular doesn’t speak to the question of what would happen over the long run if the relative pay of teachers were to change significantly. For instance, previous research has suggested that long-run changes in relative pay are linked to the average cognitive ability of individuals who choose to become teachers.

Nevertheless, the apparent weakness of the relationship between pay and outcomes may reflect a number of issues.

It may be that, when making appointments, schools find it difficult to distinguish between more and less effective teachers. That might imply a need for better information. Indeed there is a strong case for improving the availability of information about the relationship between particular teachers and the outcomes for the pupils they teach.

Pay differentials may be effective when linked more directly to performance. There is some evidence of a modest positive effect of performance-related pay on pupil attainment, though it appears to matter a lot exactly how such systems are designed.

More generally there is a case for focussing on effective advertising and promotion of teaching. The availability of (cost) effective teacher training routes (which IFS is currently researching) is likely to be important. And there may be scope to increase the quality of applicants to teacher training.

Overall there is a remarkable lack of clear evidence about which combination of measures is likely to be most effective in attracting more high quality teachers into the profession or in attracting the best teachers to particular schools. Our research suggests that modest across-the-board pay rises are not likely to be the main answer, at least in the short run.

It is normal to highlight the need for more research. It is urgently needed in this area. In particular, it is vitally important to put together data that would make such research possible. The Department for Education collects data on pupil performance. It also collects data on teachers. It has consistently, and for a long period, refused to collect the necessary information that would allow these two datasets to be linked. This means that we remain largely ignorant about which are the most and least effective teachers and which policies are most effective in helping attract and retain them.