The Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) latest forecast for the UK’s public finances – published in December 2013 – presented a significantly better picture for the UK’s fiscal position over the next five years than had been suggested by their previous forecast in March. This was the result both of higher expected economic growth up to 2018–19 and the government’s decision to continue to freeze public spending in real terms for one more year in 2018–19. In a speech this evening to the David Hume Institute, IFS Director Paul Johnson will describe how this new information affects our estimate of the outlook for Scotland’s public finances over the next five years. This observation provides more detail behind that analysis: we set out here how the new forecasts from the OBR affect the medium-term fiscal outlook for Scotland that we and the Scottish government, among others, previously presented.

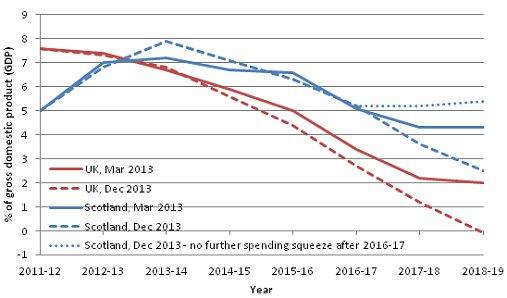

The OBR now thinks that the economy will perform better over the next few years, meaning that most of the major tax revenues will rise more quickly and public spending (many components of which have already been fixed in cash or real terms for the next five years) will decline more rapidly as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). As a result, the official forecast for public sector net borrowing in the UK up to 2017–18 was revised down significantly. This is shown by the red lines in Figure 1. In the 2013 Autumn Statement, the government also pencilled in one more year of freezing public spending. As Figure 1 shows, this (if it in fact occurs) will strengthen the public finances even further in 2018–19.

Between March and December last year, the OBR’s forecast for public sector net borrowing in the UK in 2018–19 improved from 2.0% of GDP to –0.1% of GDP (i.e. the OBR is now forecasting a surplus). Our estimates suggest that the borrowing projection implied for Scotland has fallen from 4.3% of GDP to 2.5% of GDP; these figures assume that all the spending cuts currently pencilled in by the UK government are also implemented in Scotland. In other words, both the UK and Scotland are now expected to have a stronger fiscal position in 2018–19 than was expected in March last year as a result of an improved economic outlook and the pencilling in of an additional year of spending cuts. However, it is worth noting that the OBR expects the better economic performance over the next five years to have reduced scope for further economic recovery after 2018–19. This means that the long-term fiscal improvement implied by the OBR’s new economic forecasts is somewhat overstated by the differences shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Public sector net borrowing projections for the UK and Scotland

Notes: All figures assume that the tax increases and spending cuts currently announced and pencilled in by the coalition government are implemented, including those planned in Scotland for after the date of potential independence. Sources: Figures for ‘Mar 2013’ are from Amior, Crawford and Tetlow (2013). Figures for ‘Dec 2013’ are authors’ calculations using Office for Budget Responsibility (2013), Economic and Fiscal Outlook: December 2013.

Our estimate of Scottish borrowing of 2.5% of GDP in 2018–19 assumes that all the tax increases and spending cuts currently announced and pencilled in by the UK’s coalition government are implemented, including those planned in Scotland for after the date of potential independence. If, instead, the Scottish government did not want to cut non-debt interest public spending as a share of national income after 2016−17, then borrowing in 2018−19 would be 5.4% of GDP (rather than 2.5% of GDP) – this is shown by the dotted blue line in Figure 1. In other words, to reach a position where borrowing was at 2.5% of GDP in 2018-19 the government of a newly independent Scotland would need a fiscal tightening of 2.9% of GDP between 2016-17 and 2018-19.

Oil revenues

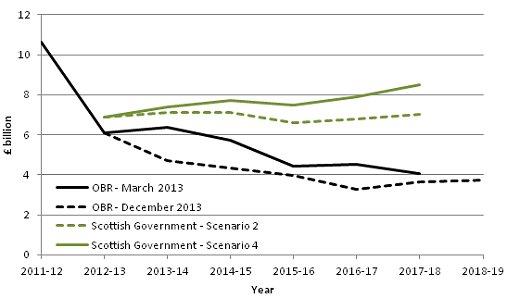

There was one source of revenues that the OBR took a more pessimistic view on in December than they had in March: that was revenues from oil and gas production. As the vast majority of these revenues are generated in Scotland, a downgrade to this revenue stream has a much more adverse effect on Scotland’s fiscal balance than it does for the UK as a whole. (Oil and gas revenues for Scotland implied by the two OBR forecasts are shown by the black lines in Figure 2.) As a result, the improvement in the fiscal position for Scotland suggested by the OBR’s December forecast (shown by the blue lines in Figure 1) is not nearly as large as for the UK – indeed, in 2013–14 and 2014–15 our calculations suggest that Scotland would have a weaker fiscal position than was implied by the OBR’s March forecast.

Figure 2: Comparing forecasts for Scottish oil and gas revenues

Notes: Scottish oil and gas revenues based on the OBR forecasts are calculated assuming that Scotland is allocated 94% of UK revenues. Sources: Office for Budget Responsibility (2013), Economic and Fiscal Outlook: March 2013; Office for Budget Responsibility (2013), Economic and Fiscal Outlook: December 2013. Scottish Government (2013), Oil and Gas Analytical Bulletin: March 2013 (http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0041/00416072.pdf).

The outlook for Scotland is, however, very sensitive to the tax revenues received from oil and gas production and some forecasters take a very different view from the OBR on the prospects for these revenues over the next few years. In particular, the White Paper published by the Scottish government in November presented figures for Scotland’s fiscal position based on a forecast that Scottish oil and gas revenues would be somewhere between £6.8 billion (described as ‘Scenario 2’ in Figure 2) and £7.9 billion (described as ‘Scenario 4’ in Figure 2) in 2016–17. We estimate that the OBR’s forecast at the time implied revenues for Scotland (allocated on a geographic basis) of just £4.5 billion and that their latest forecast implies revenues of just £3.3 billion in that year.

We estimate that the OBR’s forecasts imply that Scottish borrowing in 2017–18 will be 3.6% of GDP. However, if Scottish oil and gas revenues were to turn out as projected under the Scottish government’s ‘Scenario 2’ or ‘Scenario 4’, borrowing would instead be 1.8% or 1.0% of GDP respectively. These latter figures suggest a better position for Scotland’s public finances, similar to the position for the UK as a whole, which the OBR projects will have borrowing of 1.2% of GDP in 2017–18.

It is worth noting in this context that it looks like the Scottish government’s forecasts for revenues under these scenarios have been too optimistic in 2012–13 and, with the vast majority of payments already having been made for 2013–14, that their forecasts for this year also look to be too optimistic. It remains to be seen whose forecasts might be more accurate going forwards.

Conclusion

The latest OBR forecasts for the UK’s public finances imply a slightly stronger fiscal position for a potentially independent Scotland in the medium-term than their previous forecasts suggested, although with higher borrowing over the next couple of years. This is good news but would require the government of a newly independent Scotland to continue with the spending squeeze currently planned by the UK’s coalition government. The latest OBR forecasts also illustrate the sensitivity of Scottish public finances to oil revenues. Neither the OBR nor the Scottish government can know for sure what will happen to these revenues. What is clear is that fiscal decisions in an independent Scotland would need to be taken in the context of considerable uncertainty over this very important part of the budget – and in the context of long term pressures both on these revenues and arising from an ageing population (as we have highlighted).

This analysis has been produced as part of our ESRC funded work on The Future of the UK and Scotland. This research programme aims to clarify some of the fiscal choices that might face Scotland were it to become independent.