Inflation combined with seasonal effects hugely increase the government’s debt interest bill in June

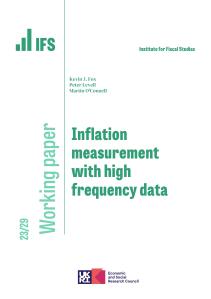

Today, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published new public finance data for the month of June, including an estimated cost of servicing the government’s debt of £19.4 billion. Figure 1 shows that at the time of the Spring Statement in March, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) already expected this figure to be very close to its outturn – in other words, extremely high. At £19.4 billion, it is more than twice as high as in the previous June and over one-quarter of the amount spent over the whole of the last financial year.

Figure 1. Government debt interest spending since April 2021

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook (March 2022); Office for National Statistics (series NMFX).

This is largely a reflection of sharply rising inflation this year. A quarter of the UK’s government debt is index-linked, which means that the cost of servicing it depends directly on inflation. Therefore, debt interest over the whole of this year will be much higher than we had become used to before the recent sharp increase in inflation. In March, the OBR forecast debt interest across the whole of this financial year to be £87 billion, which would be an increase of 25% on last year. And since March, inflation has come in above the OBR’s forecast, which will push this year’s interest payments higher still.

But another part of the extraordinarily high payment this month is a typical pattern that long pre-dates the current bout of high inflation. This pattern arises because, oddly, the measured cost of servicing index-linked debt largely depends on how the price level changed between three and two months ago. Price growth sometimes fluctuates sharply from month to month, which leads to a pronounced seasonal pattern in interest payments. Debt interest accrued in June (the figure the ONS will publish on Thursday) mainly reflects the movement in the monthly level of the Retail Prices Index (RPI) between March and April. Since many prices typically increase in April (such as council tax bills), this movement tends to be larger than at other points in the year: looking at debt interest payments since the financial year ending in 1998, debt interest accrued in June was on average 14% higher than in an average month, and more than twice as high as in March. March is typically the month with the lowest accrued payment, reflecting the fact that New Year sales depress the change in the level of the RPI between December and January each year.

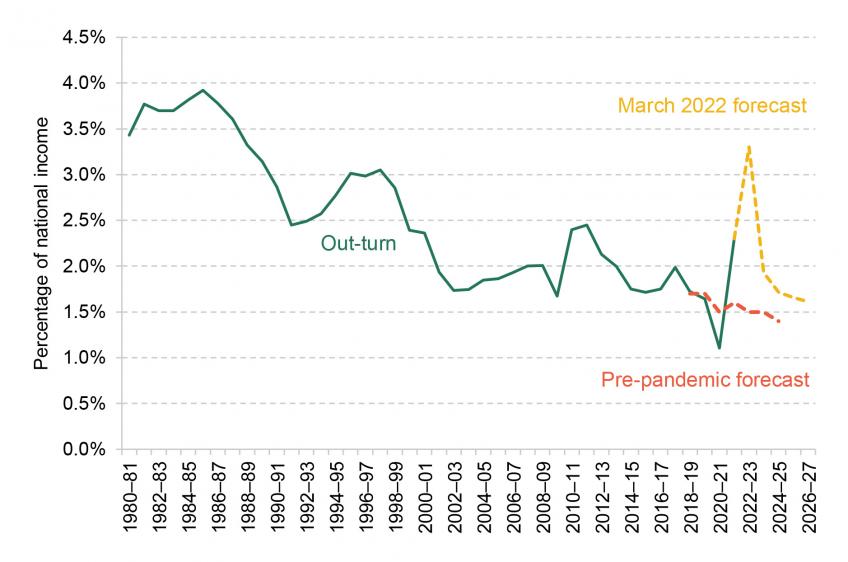

Figure 2. Government debt interest spending as a percentage of national income

Note: Central government debt interest net of income from the Asset Purchase Facility shown (ONS series NMFX and MU74).

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Public Finances Databank, https://obr.uk/data.

Figure 2 shows government debt interest as a share of national income since 1981, the year the UK first issued index-linked gilts. High inflation and higher interest rates than we had become used to in recent years are set to push debt interest spending as a share of national income this year to levels last seen in the 1980s. If, as the Spring Statement forecast assumes, price rises then return to the pace we have been more used to over the last 25 years, this will quickly be reflected in lower debt interest payments. However, inflation is already running ahead of the March forecast, and other forecasters such as the Bank of England have further increased their expectations for inflation, which may also prove more persistent. Even if inflation were to fall back quickly, as the Spring Statement forecast assumes, interest payments would remain at a higher level than expected in the March 2020 Spring Statement forecast, which did not yet incorporate any impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At £19.4 billion, today's debt interest figure for June is eye-wateringly high compared with the very low levels of debt interest we had become used to between the financial crisis and the pandemic. But this single month’s figure is driven by short-term and seasonal effects. Of greater importance is the size and any persistent increase in debt interest spending, which in large part will be determined by how quickly and how fully inflation falls back towards target.