This observation from December 2021 has been updated to reflect the figures reported in the Final Local Government Finance Settlement published on 7 February 2022.

The government has published the final Local Government Finance Settlement for 2022-23 setting out funding allocations for different councils.

Overall funding levels

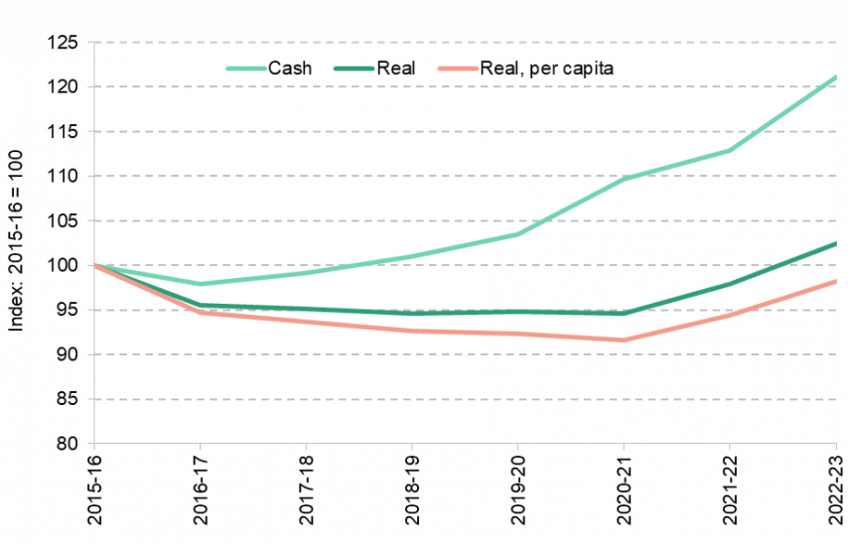

The Settlement confirmed a substantial increase in councils’ non-COVID funding next year. Total core spending power projected is to increase by 7.4% year-on-year (or by 4.6% in real-terms), from £50.4 to £54.1 billion, if councils make full use of council-tax raising powers. This is slightly more than was projected in October’s Spending Review (£53.7 billion), which councils will welcome given high and rising inflation. It is also slightly higher than set out in the provisional settlement in December (£53.9 billion), mostly due to an increase in the compensation authorities receive for under-indexing the business rates multiplier.

The planned increase will mean councils’ core spending power next year is set to be 2.4% higher in real-terms than in 2015-16. However, population growth means that it will remain 1.8% lower per person in real terms than in 2015-16 – and much lower than back in 2010 prior to austerity commencing.

Figure 1. Local government core spending power, 2015-16 to 2022-23

Source: Final Local Government Finance Settlement, 2022-23; OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook, October 2021.

The distribution of funding across councils

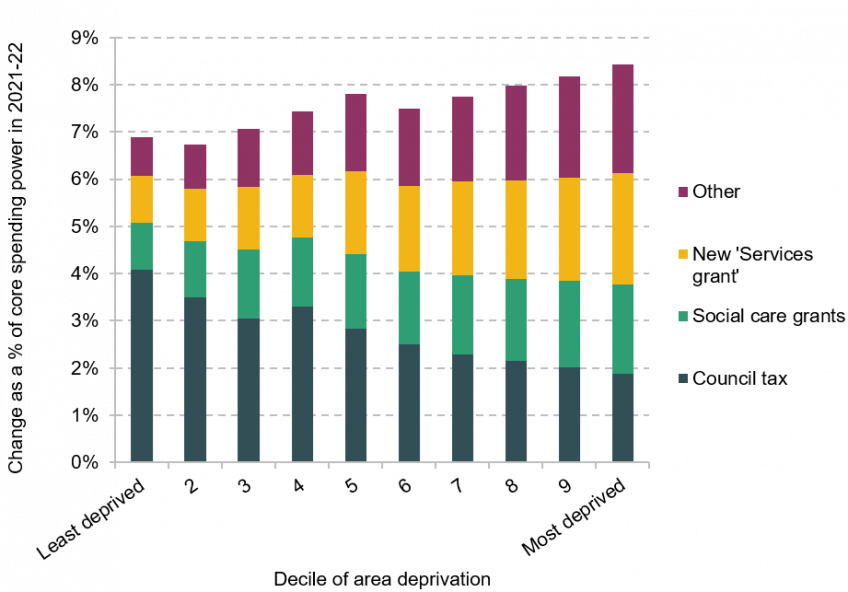

In contrast to the last decade, councils serving more deprived parts of England will see bigger increases in funding than those serving more affluent areas next year. The most deprived tenth of councils are projected see their core spending power rise by 8.4% (5.6% in real-terms), compared to 6.9% (4.1% in real-terms) for the least deprived tenth of councils.

This reflects the fact that while more deprived councils are expected to generate less from council tax increases, this will be more than offset by the targeting of increases in grant funding at such councils.

Figure 2. Projected change in core spending power between 2021-22 and 2022-23, by deprivation decile group

Note: Deprivation deciles are based on IMD 2019 Average Score at the upper-tier authority level.

Source: Final Local Government Finance Settlement, 2022-23; English Indices of Deprivation, 2019.

For example, the settlement includes a new ‘Services grant’, worth £822 million, which is intended to support all services delivered by councils. This will be distributed in proportion to the business rates and grant funding councils received in 2013-14. As this part of councils' funding was designed to provide more to councils with higher spending needs and/or less ability to raise council tax, it is unsurprising that this approach gives councils in deprived areas a large share of this new grant.

The Settlement reminds us that reform is overdue

The fact that allocations from 2013-14 have been used to allocate funding in 2022-23 reminds us that the local government finance system is becoming increasingly out of date. Patterns of need are likely to have changed, perhaps substantially, in the intervening years. As an illustration, the population of Tower Hamlets is estimated to have increased by 21% between 2013 and 2020, while the population of Blackpool is estimated to have fallen by 2%.

This illustrates why it is so important that progress is made with the Fair Funding Review, which will provide both updated needs assessments and a reformed finance system that balances these needs assessments with other government objectives such as financial incentives for growth. It is therefore welcome to see the Secretary of State commit to work with local government and other stakeholders to complete and consult on this Review over the coming months.

Such reforms to how funding is allocated will inevitably create winners and losers. And with the Spending Review suggesting much smaller increases in overall funding in 2023-24 and 2024-25 than next year, the government will be facing tricky trade-offs in how to address this challenge. In particular, how does it balance providing transitional protection to the losers with allowing the winners to see the funding increases the updated system says they are due?

This challenge may be one reason why the government has said the new ‘Services grant’ is a one-off grant that will not be taken into account in any transitional protections. This will give a little more wiggle-room in how it implements these vital but difficult funding reforms.