This article was first published in the British Tax Review as part of the Finance Act 2021 Notes and is reproduced here by kind permission of the publishers, Thomson Reuters.

Background

The UK’s public finances are under pressure. The one-off costs of supporting the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the expected longer-term after-effects of the pandemic on the economy and on demand for public services, arrived on top of immense pre-existing challenges: the looming costs of dealing with climate change, an ageing population, rising concern about inequalities and a “levelling up” agenda. And all in the context of Brexit and an apparently long-term decline in productivity growth which make it harder to rely on economic growth to rescue the public finances.

With funding for public services (except health) and social security benefits (except for pensioners) already tightly squeezed over the past decade, it was widely predicted that tax rises would shoulder more of the burden of shoring up the public finances this time than they did after the 2008 financial crisis.

So, apparently hemmed in by a manifesto pledge not to increase the rates of the three biggest taxes—income tax, National Insurance contributions and value added tax (VAT)—the Chancellor turned to the fourth-biggest tax, corporation tax, to start delivering revenue.

The rate increase in context

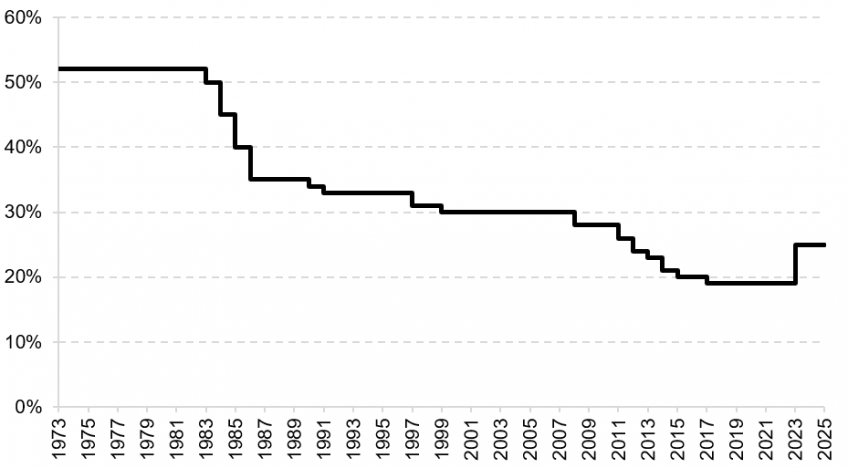

The rise he announced was a substantial one. Section 6 of the Finance Act 2021 (FA 2021) increases the main rate of corporation tax by six percentage points, from 19 per cent to 25 per cent, with effect from the financial year beginning 1 April 2023. The rise looks even bigger when one considers that, up until the 2020 Budget,[1] the rate had been due to fall from 19 per cent to 17 per cent in April 2020. Corporation tax is now heading to a very different destination from that envisaged in George Osborne’s last Budget.[2] It is also a different direction of travel from that taken by successive previous governments: the first rise in the main rate of corporation tax for half a century. At the same time, we should not exaggerate the size of the change: at 25 per cent, the rate will still be lower than it was in 2011, let alone the 52 per cent peak it reached in the 1970s and early 1980s (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: the main rate of UK corporation tax[3]

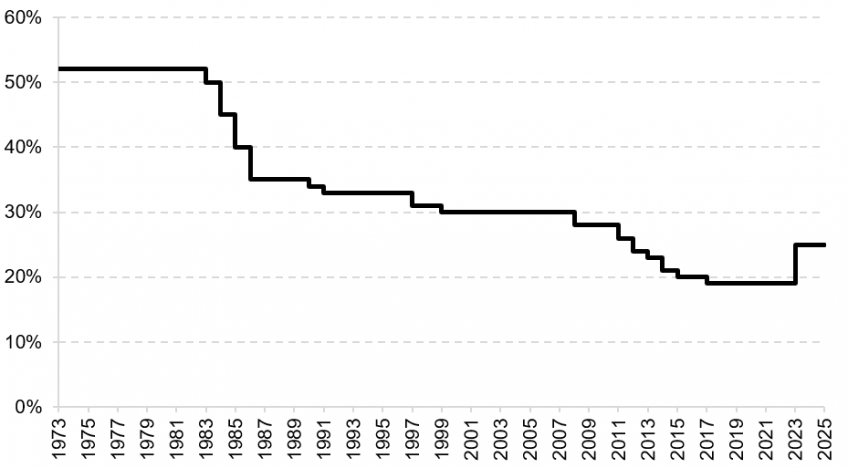

The stated objective is “to raise revenue whilst keeping the UK’s rate of Corporation Tax competitive relative to other major comparable economies”.[4] The UK’s rate will move from one of the lowest in the OECD to slightly above average (see Figure 2), but it will still be the lowest in the G7 (once sub-national taxes are taken into account)—if other countries do not change their own tax rates by then. For several decades, the trend across the world has been for headline corporate tax rates to fall; but given how far rates have now fallen across the world and the fiscal pressures that all governments now face, there are reasons to think the trend might slow down or even go into reverse. Not all governments have tied their hands on other revenue-raising options as much as the UK’s has, so they might have less need to turn to corporation tax to replenish their coffers. But current moves towards international action, potentially including a minimum corporation tax rate (albeit a low one), do not smack of a burning desire to continue the “race to the bottom”.

Figure 2: overall headline corporation tax rates in the OECD, 2021[5]

The UK looks less internationally competitive once the whole of the corporation tax regime, rather than just the headline rate, is taken into account. The UK taxes an unusually broad measure of profits: in particular, except while the temporary “super-deduction”[6] is in place, the UK has the G7’s least generous allowances for plant and machinery investment beyond the annual investment allowance (AIA). So the UK’s effective corporate tax rates on investment will be middling among the G7 despite having the lowest headline rate.[7] In any event, the UK will certainly be less internationally competitive with a 25 per cent tax rate than if it kept its current 19 per cent rate.

The rise in the main rate of corporation tax will not affect all taxable company profits. It will not apply to profits subject to the patent box, or to ring-fence profits from North Sea oil and gas, or—thanks to the re-introduction of a small profits rate[8]—to companies making relatively small profits. It will technically apply to banks, but the Budget announced that the corporation tax surcharge banks currently pay will be reviewed so that “the combined rate of tax on banks’ profits does not increase substantially from its current level”—seemingly implying a reduction in the bank surcharge to offset the increase in the main rate, though at the time of writing the specifics have not yet been announced: the Budget said the government will set out its plans in the autumn.[9]

The six percentage point rise in the main rate of corporation tax will, though, be mirrored by a six percentage point rise in the main rate of the diverted profits tax, from 25 per cent to 31 per cent—legislated as section 8 FA 2021, and again effective from 1 April 2023—in order to maintain the differential between the tax rate on ordinary profits and that on profits deemed to have been artificially diverted away from the UK. (The rates of diverted profits tax for profits falling within the North Sea ring-fence or the bank surcharge remain unchanged at 55 per cent and 33 per cent respectively.) The diverted profits tax raises negligible revenue, but that does not necessarily make it a failure, since its main objective is to deter aggressive avoidance rather than to raise revenue directly.

Long-run economic and revenue consequences

Budget 2021 reported that the government expects the rise in corporation tax for companies with large profits (allowing for the reintroduction of the small profits rate) to raise £17 billion a year by 2025–26.[10] However, it is important to note that while this estimate allows for some profit-shifting out of the UK in response to the tax rise, it does not allow for any reduction in UK investment. The higher corporation tax rate will make the UK a less attractive place to invest. The higher rate will also exacerbate all of the other problems that corporation tax creates, notably the bias towards using debt rather than equity finance. (Sadly, the reintroduction of a small profits rate means that the tax rise will not even have the redeeming feature of reducing the incentive for tax-motivated incorporation.) All tax rises come with their own disadvantages, of course, and increasing corporation tax was by no means the worst option the Chancellor could have picked. The consequences will be less severe than if the UK were starting from a higher tax rate. But if, as a result of the corporation tax increase, there is less investment in the UK and more of it is financed by debt—the interest on which is tax-deductible—we would expect the long-run yield from the reform to be considerably less than £17 billion a year.

Short-run timing effects and the super-deduction

Looking more at the short term, announcing a tax rise two years in advance gives companies time to plan. However, on its own it would create an especially strong disincentive to invest before the tax rise comes into effect: investment costs incurred before April 2023 would only be deducted at a 19 per cent tax rate, while investment returns received after April 2023 would be taxed at 25 per cent. By delaying investment until 2023, companies could benefit from more valuable deductions, commensurate with the higher tax rate they face on their income.

Hence the need for a super-deduction for investment in the meantime, the timing and rate of which seem to have been chosen specifically to counteract this disincentive: allowing 130 per cent of expenditure to be deducted with a 19 per cent tax rate is almost exactly equivalent to allowing 100 per cent of it to be deducted with a 25 per cent tax rate.[11] For qualifying investments up to the AIA, the super-deduction effectively neutralises the disincentive effect of pre-announcing a tax rate rise; the fact that the super-deduction is uncapped is like removing the cap on the AIA (and thus the disincentive to invest more than the AIA in qualifying assets) for two years, and is a genuine additional incentive to invest during that period.

The reintroduction of the small profits rate complicates matters. For companies that expect to continue paying 19 per cent, the super-deduction is an outright investment subsidy[12]; while for those expecting to be in the marginal relief bracket (with annual profits between £50,000 and £250,000), the super-deduction is not big enough to neutralise the disincentive effect of preannouncing what is effectively a rise in their marginal tax rate to 26.5 per cent.

Even for companies facing the main rate of corporation tax, the super-deduction does not completely neutralise the timing distortions caused by preannouncing a tax rate rise. While the lack of a cap on the super-deduction encourages companies to bring forward qualifying investment above the AIA to before April 2023, capital expenditure that does not qualify for the super-deduction—and revenue expenditure that will generate income after April 2023—is still strongly discouraged by the forthcoming tax rise. And, separately from any effects on investment decisions, companies that can do so have an incentive to realise chargeable gains or bring forward income to before April 2023.

All of this changes, of course, if one believes that—as some have suggested—the government might not in the end go ahead with such a sharp rise in the corporation tax rate in April 2023. Whatever they believe, companies and their tax advisors have plenty to keep them busy in the couple of years ahead.

[1] HM Treasury, Budget 2020: Delivering on Our Promises to the British People (11 March 2020), HC 121.

[2] HM Treasury, Budget 2016 (March 2016), HC 901.

[3] Note: the horizontal axis has April of each year marked. Source: IFS, “IFS Fiscal Facts” (last reviewed 10 June 2021) IFS TaxLab, https://ifs.org.uk/taxlab/data-item/ifs-fiscal-facts [Accessed 25 August 2021].

[4] HMRC, Policy Paper, Corporation Tax charge and rates from 1 April 2022 and Small Profits Rate and Marginal Relief from 1 April 2023 (3 March 2021), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/corporation-tax-charge-and-rates-from-1-april-2022-and-small-profits-rate-and-marginal-relief-from-1-april-2023/corporation-tax-charge-and-rates-from-1-april-2022-and-small-profits-rate-and-marginal-relief-from-1-april-2023 [Accessed 28 August 2021], under “Policy objective”.

[5] Note: includes sub-national (e.g. state or local) taxes. Darker bars are G7 countries. Source: OECD, Tax Database, Table II.1, https://stats.oecd.org/ [Accessed 25 August 2021].

[6] Discussed in Andrew Harper, “Finance Act 2021 Notes: Sections 9–14: capital allowances: super-deductions etc” [2021] BTR XXX.

[7] See Michael Devereux, “What will the 2021 Budget do for corporate investment?” [2021] BTR 121.

[8] Discussed in Lynne Oats, “Finance Act 2021 Notes: Section 7: small profits rate chargeable on companies from 1 April 2023; and Schedule 1: small profits rate for non-ring fence profits” [2021] BTR XXX.

[9] HM Treasury, Budget 2021: Protecting the Jobs and Livelihoods of the British People (March 2021), HC 1226, para.2.82.

[10] HM Treasury, Budget 2021: Protecting the Jobs and Livelihoods of the British People (March 2021), HC 1226, Table 2.1, p.42, line 22.

[11] It is also telling that, unlike most capital allowances, the super-deduction is not available for unincorporated businesses, which do not face a tax rate increase in 2023.

[12] The same applies for investments whose returns will fall within the patent box and therefore continue to be subject to a 10% tax rate. As noted above, the situation for banks remains to be seen.