This article was first published by Taxation and is reproduced here with full permission. Download a pdf version here.

The parts of the UK tax system that dictate how different forms of income are taxed are not fit for purpose. Employees’ salaries attract thousands of pounds more in tax each year than the incomes of people who are self-employed or working through their own company. This is unfair and pushes people towards working through their own business rather than as employees. At the same time, the tax system discourages investing in a company and taking risks.

These problems can be solved. Fixing them completely would require radical, large-scale reform. But, short of that, there are plenty of steps that could be taken towards a better tax system.

The problem

There are now about five million people obtaining income from self-employment and about two million company owner-managers. That is one in five of the UK’s workforce working through their own business. Their numbers have been growing rapidly – up from about four million and one million respectively 20 years ago – in part because their incomes are taxed at much lower rates than the incomes of employees doing similar work.

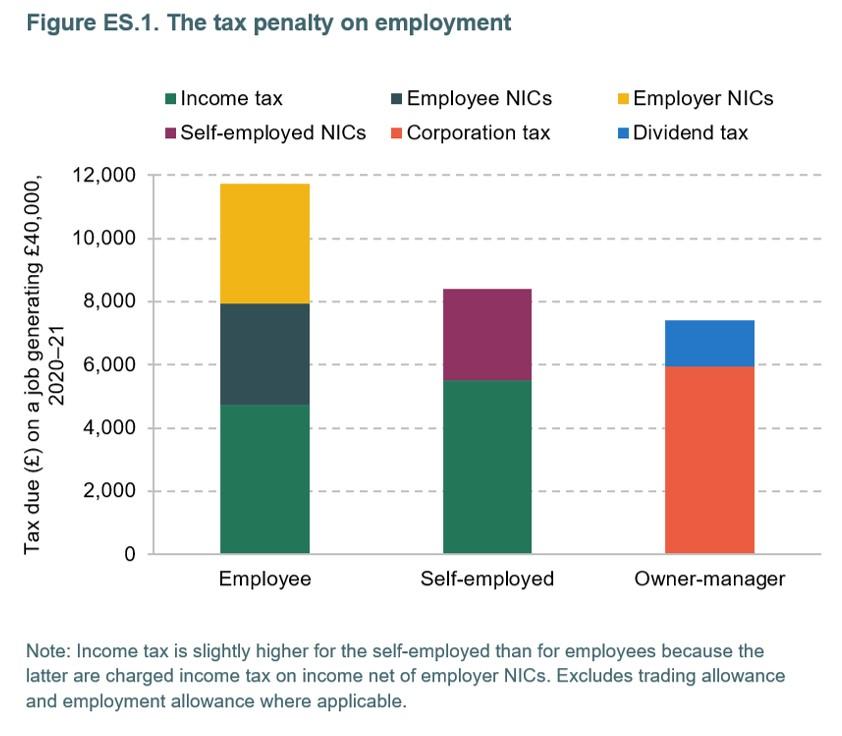

For a job generating £40,000, tax in 2020-21 is £3,300 higher if the job is completed through an employment contract rather than by someone who is self-employed, and £4,300 higher than if they work through their own company (see Chart). This is mostly because employees’ salaries are subject to employers’ National Insurance contributions (NICs) whereas other incomes are not. The differences can be even greater than this, because the UK continues to levy much lower tax rates on capital gains than on earned income – something that overwhelmingly benefits the wealthiest, with almost two-thirds of taxable capital gains realised each year being made by people realising gains of more than £1m that year.

The problems with this are almost self-evident when similar work is being done by people who are employed, self-employed or working through their own company. It is unfair that people who make the same income from doing similar things face very different tax bills, and it creates strong pressure for people to work through a business for tax reasons even when it is not what they would otherwise choose.

People running a business are often not just doing similar work to employees: they may be employing people themselves, investing, trying out new ideas and taking risks. The tax system needs to account of these different activities, but the way it does so at the moment is a mess. How much tax actually ends up being charged varies widely depending on factors such as the asset type, source of finance and duration and riskiness of investments as well as the legal structure involved. Taxes create an incentive to borrow, a disincentive to invest equity in companies, a bias towards investing in some assets rather than others, a disincentive to take risks, and an incentive to hold on to assets for longer than commercial considerations would dictate.

While tax is rarely the main factor influencing people’s decisions, there is strong evidence that it does affect behaviour in all of these ways. Distorting individuals’ and firms’ decisions reduces economic output and well-being. It would usually be better for people to do what they think best personally and commercially.

The wide range of different tax treatments applied also creates complexity. The presence of boundaries in the tax system implies the need to devise, administer, comply with and police rules to distinguish different legal forms – not only whether someone is really working as an employee (the notorious IR35 and employment status tests) but also, for example, whether a particular receipt represents income or capital gain and whether a particular outgoing is a current expense or an investment.

These, in turn, impose costs by diverting officials, taxpayers, tax practitioners and occasionally the courts from more productive activities.

The current system persists despite these problems in part because of a widespread belief that the system is justified – that there are benefits that offset the costs imposed by differentiating tax by legal form. However, none of the common arguments holds up.

Levying lower taxes on the self-employed cannot be justified by differences in publicly funded benefits – the differences in benefits are far smaller than the tax advantages. Nor can they be justified by differences in employment rights, which make employment more attractive to workers but less attractive to potential employers.

Further, preferential tax rates on capital gains, dividends and self-employment income are not well targeted at encouraging entrepreneurial risk-taking and investment. The biggest giveaways go to those who make large profits without investing much money. Those who make substantial investments in a business for a modest return or who risk making a loss – those most likely to be deterred from investing – are penalised by the tax system. Current policy is indefensible.

Long-run solution

The policy challenge is to tax income and capital gains from business and investment at the same overall rates as labour income without creating barriers to saving and investment. As things stand, simply increasing tax rates on income from business, to bring them closer to tax rates on employment, would worsen the existing distortions to investment and risk-taking.

There is a theme to the policy mistakes that have been made in the past. In effect, policymakers – in the UK and elsewhere – have been trying to use tax rates on business and investment income to pursue two goals: to tax all income the same, and to avoid discouraging saving and investment.

These two goals appear to be in tension. The desire to create a fair and simple system and stop tax-motivated changes in legal form suggests that tax rates on income from capital should be similar to those on income from employment. But the desire to ensure that tax does not penalise saving and investment is often used to support lower tax rates on capital. The yo-yo history of capital gains tax provides a clear example of how politicians at different times have chosen different points on this perceived trade-off. We are left with an awkward compromise that achieves neither aim and is therefore subject to constant tinkering.

These two goals can, however, both be achieved and the tension overcome. The key is to realise that we have two instruments available to pursue these two objectives: not only tax rates, but also the tax base – the definition of what is taxed. There is no need to compromise: we can align tax rates across all forms of income, while reforming the tax base to avoid discouraging saving and investment.

Align tax rates

Aligning tax rates is not quite as simple as it seems. It is not just a matter of applying standard income tax rates to all income and capital gains. To achieve full alignment, we also need to take account of the employer and employee National Insurance contributions levied on employees’ earnings, and of the corporation tax levied on company profits before they are distributed to shareholders, as in the chart.

After that is understood, the adjustments required are not complicated. There are many combinations of rate changes that could achieve alignment and, overall, tax rates could be levelled up to current employment tax rates, levelled down to current capital tax rates, or set somewhere in between.

Reform the tax base

Alongside aligning tax rates, we need to reform the tax base. This is a more effective tool than tax rates for ensuring that taxes do not discourage investment. The tax base can be designed to ensure that marginal investments – those that are only just worthwhile – are not taxed, minimising the effect of tax on investment decisions, while ensuring that tax is paid in full on more profitable projects which are likely to go ahead anyway. In contrast, reduced tax rates can still deter marginal projects while also giving unjustified support to non-marginal activities.

To reform the tax base, we should give full deductions in both personal and corporate taxes for amounts saved or invested and allow losses to be offset against as broad a set of income as possible. There are various ways this could be achieved. Done properly, it could not only remove disincentives to save and invest but also remove distortions between different types of assets and sources of finance, remove disincentives to reallocate capital, reduce disincentives to take risks and ensure that tax incentives do not vary with inflation.

With a reformed tax base, tax rates could be aligned across all forms of income while investment incentives would be improved.

New ideas for practical steps in the right direction

Moving straight to the long-run solution would be a big reform creating a lot of winners and losers, and might be hard to achieve in the short run. But piecemeal reforms risk being the policy equivalent of ‘whack-a-mole’, alleviating one problem at the expense of making others worse. For example, increasing tax rates on self-employment would bring them more into line with those on employment but, on its own, it would worsen the existing distortions to investment and risk-taking and would further encourage people to set up companies instead.

In a new report Taxing work and investment across legal forms: Pathways to well-designed taxes, we suggest a range of smaller reform packages which would be steps on the way to a better system and would also improve the system compared with today. There is no one ‘right’ path to the long-run ideal; our report discusses a number of possible options, including, for example:

- Tax rates on dividends and capital gains could be increased to standard income tax rates, as a move towards full alignment, while people who buy new shares in a company – including their own company – could receive income tax relief on the investment, paying tax when they take their money out instead (like with a pension). This would remove disincentives to invest in a company while also ensuring tax is paid at full income tax rates on the proceeds of that investment.

- Tax rates on self-employment income could be increased, but self-employed people who make a loss and have no other income that year could be allowed to deduct the loss from income from their next job or business venture, not just future profits from the same trade. Similarly, capital gains tax rates could be increased while allowing capital losses to be offset against income, rather than capital gains, in a wider range of circumstances than now – though with relief for individuals’ capital losses restricted to the capital gains tax rate, not the income tax rate. All losses could be carried back for up to five years, rather than the current three, one or zero years in different cases. Such changes would align tax rates more closely while reducing disincentives for risky entrepreneurial activity.

- Tax rates on dividends and capital gains could be increased but indexation of capital gains for inflation reintroduced, so that only above-inflation gains were taxed. Indexation for inflation need not be as complicated as it was in the past, and it would both reduce avoidance incentives and reduce disincentives to save and invest.

These types of packages move away from blanket tax reductions for anyone whose income is labelled as ‘business income’ towards targeted measures that reduce the tax penalty for those who invest or take risks.

There is no pain-free way to fix the current tax system: any meaningful reform will create losers as well as winners. But keeping the status quo is also a choice – one that unfairly penalises ordinary employees and investors, and creates inefficiency and administrative costs that make us all poorer. A challenge for those who do not like the particular reform packages we highlight is to devise alternatives of their own. Rejecting all reform means choosing the current system; surely we can do better.

Shadow of Covid-19

The Covid-19 disaster has brought many challenges that will last for years to come. But the pandemic does not alter the fundamental problems we have identified. Nor does it change the long-run solution. The problems that are driven by flawed tax policy will be fixed only by better tax policy.

It will be even more important to fix these problems after the crisis. We are likely to see a move towards higher taxes in the medium run. This is because the permanent economic damage from the pandemic will undermine tax revenues and in response to demands for higher spending. In the search for extra revenue, removing preferential tax rates would be a natural place to look.

However, simply raising taxes on income from business when the system is so poorly designed risks creating more inequity and stifling the economic growth that we need. Higher taxes have the potential to exacerbate the problems caused by structural weaknesses in the system, and make it even more important to design tax policy well. In the wake of the pandemic there may also be a greater focus on economic inequalities, the quality of work and a fair distribution of the tax burden. The issues we highlight matter for all of these.

Covid-19 will also change the political economy of tax reform.

In spring 2020, when announcing the introduction of the self-employment income support scheme (SEISS), the chancellor of the exchequer laid the groundwork for future rises in taxes on the self-employed, saying: ‘In devising this scheme – in response to many calls for support – it is now much harder to justify the inconsistent contributions between people of different employment statuses. If we all want to benefit equally from state support, we must all pay in equally in future.’

The SEISS can be seen as evidence that not only are standard state benefits almost as generous to the self-employed as to employees, but the unspoken promise of emergency support the government provides to the self-employed is comparable to that for employees.

On average, the SEISS has been roughly as generous to the self-employed as the coronavirus job retention scheme has been to employees. Some self-employed people have been overcompensated by the scheme, resulting in a higher income than they had before the crisis, while others have fallen through the gaps.

About 40% of those receiving any self-employment income before the crisis – 18% of those receiving more than half of their income from self-employment – are ineligible for the SEISS. Further, most company owner-managers have received little or no government support of this kind. This will make it harder to raise taxes on these groups. Yet the fact that the government has struggled to target support for the self-employed accurately during this crisis is a weak argument for permanently maintaining across-the-board low tax rates for business owner-managers.

Prize worth aiming for

In light of the challenges ahead, reformed taxes offer a significant prize. Better-designed taxes would allow us to raise more revenue with less economic harm. More specifically, tax reform could aid the economic recovery and help us to ‘build back better’.

We lay out proposals that would improve incentives for businesses to invest, employ people and take risks, and would do less to push people away from employment and into other forms of work that they may not prefer. Policymakers could choose a reform pathway that helps improve the structure of the tax system while also aiding the recovery and the rebuilding that are to come.