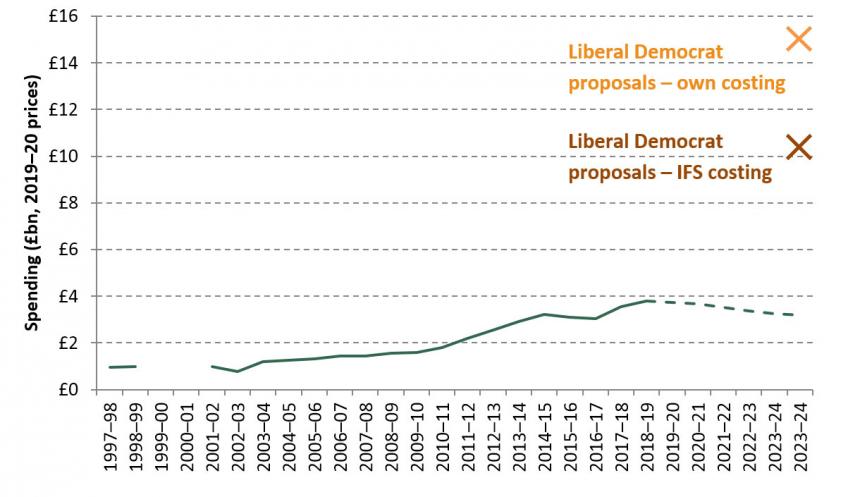

The Liberal Democrats’ manifesto, published today, puts childcare front and centre. The party is promising to spend – on its own costing - £13 billion on free childcare in 2024 (plus another £1 billion on Sure Start children’s centres). That’s almost £12 billion of free childcare spending in today’s prices – and a far sight more than the £3.7 billion we spend on free childcare in England today.

This will no doubt be welcomed by families with young children, who are set to see a big boost to their incomes from lower childcare costs. But what will this proposal mean for children’s development and their parents’ working patterns? And how does it fit in with the current, complicated landscape of childcare support in England?

What are the proposals, and what could they cost?

The Liberal Democrats plan to make every part of the free childcare system more generous: boosting the entitlement to 35 hours a week (up from 15 or 30 hours today), covering 48 weeks of the year (up from 38 weeks today), for all (rather than some) 2-, 3- and 4-year-olds and some (rather than none) of the under-twos, and funded at higher rates per hour than are currently in place.

These are big promises, and they come with a big – and uncertain – price tag. We estimate the total cost of the Liberal Democrats’ promises at £7.2 billion (in today’s prices), with extra spending for devolved administrations adding another £1.3 billion. But higher-than-expected take-up could easily push the cost in England to £8.6 billion in today’s prices, if not even higher. The £12 billion that the Liberal Democrats have allocated suggests that they might expect take-up rates to be even higher still.

The scale of this spending commitment matters: it represents an enormous increase in spending on early years, and a big change in the generosity and coverage of the welfare state for young children. Done well, this could support children’s development or help more parents – especially mothers – to combine work with raising a family. But spending this much new money, this quickly, and doing so effectively, is a tough challenge – one that will determine whether the programme has benefits beyond transferring money to families.

Figure 1: Public spending on free childcare (historical and forecast), 2019–20 prices

Note: Only includes proposals for free childcare (excludes additional spending on Sure Start and paternity leave). Costs are based on IFS estimates for 2024–25 policies. Policy baseline is shown in dashed line and incorporates population change and 2019 Spending Round allocations, then assumes a cash-terms freeze in per-hour spending at 2020 levels. Incorporates an ‘upper bound’ of savings through the tax and benefit systems. Excludes additional funding due to devolved administrations under these plans. For details of IFS costing, see Farquharson (2019), “Proposals for the early years in England”.

Who will be affected?

Since the Liberal Democrats are also planning to increase the number of funded hours – from 15 or 30 to 35 hours a week, and from 38 to 48 weeks of the year – all 2- to 4-year-olds are set to see an increase in their childcare entitlement. That’s about 1.9 million children in 2024 – roughly the same as the population of the North East Combined Authority. Adding in the roughly half of children aged 9 months to 2 years living in ‘working’ families could add another 400,000 newly-entitled kids – more if the policy encourages more parents to enter paid work, or to earn more. Overall, this package would roughly triple the number of hours of free childcare potentially available.

What does this mean for the shape of the childcare system?

The most notable feature of the Liberal Democrats’ package is the push to universalise the entitlement for 2- to 4-year-olds – equalising childcare entitlement for children in this age group, regardless of a child’s background or his or her parents’ working patterns. This shifts the free childcare programme away from targeting children and families who are perceived to have more need for – or more to gain from – childcare.

A universal model might benefit those on low incomes, for example if children from poor families are more likely to use a universal service or if parents with access to childcare during their job hunt found it easier to return to paid work. But it is also costlier and may lead to greater ‘crowding out’, with the government paying for childcare that families would have used anyway. And to the extent that childcare promotes child development, removing the 2-year-old targeting at disadvantaged children would remove one element of the system that tries to reduce inequalities between children from poorer and better-off families.

We estimate that the party would spend about £4.7 billion (in today’s prices) on a more generous free childcare offer for 2- to 4-year-olds, compared to about £3.4 billion on the under-twos in working families (though the latter costing in particular is highly uncertain). These would be offset by some savings through the tax and benefits systems, which we put at about £0.9 billion.

These plans would dramatically speed up ongoing trends in the shape of the childcare support system in England: towards spending on free childcare and away from subsidies through programmes like tax-free childcare and the benefits system; towards spending on universal programmes and away from spending targeted at low-income families.

What might this mean for children and their parents?

Parents with young children will doubtless welcome the new free childcare entitlements, which will reduce their childcare costs. But it’s less clear that the policy will deliver wider benefits, in terms of moving more parents into paid work or supporting children’s development.

Evidence for the current free childcare system suggests that full-time childcare moves some mothers into work, but only if their youngest child is affected, and even then the effects are relatively small: employment rates rise by about four percentage points when moving from part-time to full-time care (delivered through the school system). These estimates are for 3- and 4-year-old children; of course, parents with children under age two could behave differently, making the effect hard to predict in advance.

Nor is there strong evidence that England’s free childcare system has benefitted children’s development. Researchers evaluating the part-time entitlement for 3- and 4-year-olds found small benefits for children’s test scores, but these disappeared within a few years. And a report looking at the 2-year-old offer found little evidence to suggest that it has played a major role in closing the attainment gap (though the authors also note that the outcome measure they use is not very sensitive).

In other countries, free or subsidised childcare can boost the employment of parents or help children to develop. But it’s rare to see a programme that accomplishes both goals at once – more typically, programmes (like in Canada) that move mothers into work have small or negative impacts on children, while those (like in Scandinavia) that have big benefits for child development tend not to affect working patterns very much.

Summing up

The Liberal Democrats are promising an enormous increase in spending on free childcare that will greatly increase the scope of the welfare state in the early years. Parents with young children will certainly welcome more support with their childcare costs. But ensuring that this new spending provides an opportunity to improve the existing free childcare system – which, at least based on available evidence, delivers only small benefits in terms of parents’ working patterns or children’s development – will need clarity about what the priorities are and mechanisms in place to ensure that the money delivers on those aims.

The Liberal Democrats’ manifesto promises that their free childcare policies will both tackle the “achievement gap between richer and poorer” children and help “parents who want to work”. But they should be wary of claiming that free childcare will provide this ‘double dividend’ of benefits for both parents and children – indeed, ensuring that England’s free childcare programme delivers progress against one of these goals would already be a big first step.