This study is among the first to rigorously demonstrate potential of life skills interventions to change key outcomes of adolescent girls living in contexts where girls and women continue to be caught in a vicious cycle of low levels of human capital, low labour force participation rate, low wages, low bargaining power within the household, early marriage and high fertility. The results of this trial suggest that life skills and empowerment interventions can have significant positive impacts on key outcomes such as schooling, marriage and mental health that have the potential to result in permanent improvements in the life trajectories of girls and their children. Further, it sheds light on some key mechanisms including the important protective role that schooling plays in contexts where early marriage is prevalent, as well as the critical contribution of the wider community environment to girls’ mental health. Finally, it offers a blueprint for scalable and cost-effective programmes for improving outcomes of adolescent girls which aligns closely with the priorities and current approach of the government of India.

Background

Women in developing countries continue to be disempowered facing multiple constraints which prevent them from investing in their human capital and breaking the cycle of dependence on men. These include high youth unemployment, low wages, as well as early marriage and child-bearing (World Bank, 2007; Jayachandran, 2015). India is a particularly salient case. Norms and attitudes centred on the primacy of men as decision makers and on women as holding a family’s honour create environments where it is difficult for young women to pursue their education, where many marry early and where they are unequipped with the skills and knowledge needed to make choices that are optimal for their future.

There is some encouraging evidence suggesting that interventions which jump-start women’s human capital through building up different skills may have the potential to set them on a better trajectory (e.g. Case & Paxon, 2013; Adhvaryu et al, 2016). From a developmental perspective, adolescence is an opportune time for such interventions as this is a period of profound transformations in the brain, particularly in the development of higher cognitive functions and socio-emotional skills which are critical for long-term success (Heckman & Rubinstein, 2001; Heckman et al, 2006; Fuhrmann et al, 2015) offering a ‘window of opportunity’ during which appropriate interventions may have lifelong impacts (Eldreth et al, 2013).

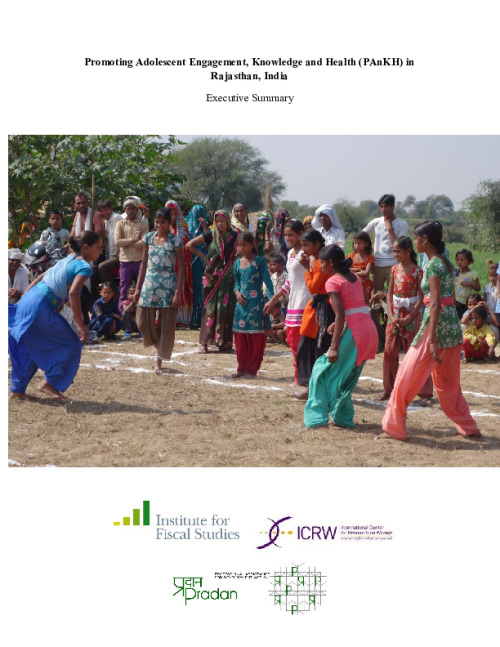

The Indian government has shown a growing interest in adolescent girls with a number of policies and programmes initiated over the last two decades. The focus of these has gradually broadened from those restricted to girls’ physical health and school attendance, to include life skills, empowerment and knowledge of sexual and reproductive health. The aim is to target the barriers that adolescent girls face to securing better economic and psychosocial outcomes. These include programmes such as Beti Bachao Beti Padao (BBBP) and Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakarm (RKSK). A key feature of the approach favoured by the government is targeting key outcomes through building life-skills and raising empowerment using community-based approaches and relying on peer educators. The PAnKH programme evaluated in this study, was designed to be a blueprint for scalable and cost-effective programmes for improving outcomes of adolescent girls in this way.

The aims of PAnKH and its community-based approach are similar to existing government programmes. However, in designing PAnKH we aim to hone in and refine key implementation features that are likely to be critical for programme effectiveness. More generally, there is little evidence on how effective stand-alone life-skills and empowerment programmes are at impacting key outcomes of adolescent girls, especially in contexts where girls are particularly disempowered and have even less say on key decisions regarding, among others, their schooling, marriage and family planning than do girls in many other developing country settings. The aim of this study is, therefore, to also add to the broader state of knowledge on the potential of life-skills and empowerment programmes to improve life outcomes of adolescent girls living in deprived contexts with low levels of female empowerment.

Programme Impacts

- Girls in both intervention arms were significantly more likely to be attending school at endline than girls in the control group. Girls in both treatment arms were just under 4 percentage points more likely to be attending school at endline than girls in the control group. This is equivalent to a 7 percent increase relative to the control mean attendance rate at endline of 54%. Effects appear to be driven by the older girls in the sample. While impacts are not significant among girls who were 12-14 at baseline, there is a 6.5 percentage point increase in the probability of attending school at endline among the 15-17 year old girls in both arms, which is equivalent to a 19 percent increase relative to the control mean. Interestingly, we also see that among the girls who are still at school at endline, there is a significant reduction in the days of school missed in the girl only and integrated arms.

- There is suggestive evidence that PAnKH had an impact on marriage rates among older girls, age 15-17 at baseline. The proportion of girls in the girl only arm in this age-group who were married by endline is nearly 16 percent lower than in the control group. While the impact in the integrated group is not statistically significant it is only slightly smaller than that in the girl only group and the two are not significantly different from each-other.

- The education and marriage effects set in at the ages when girls in the control group experience the sharpest decline in school attendance and rise in marriage.

- Mediation analysis results suggest that delays in marriage in the treatment group are explained by girls staying at school longer.

- Adolescent girls experienced significant improvements in their mental health and a reduction in tendency to victim-blaming for experience of violence when the programme targeted the wider community environment in addition to the activities with the girls themselves. There is an overall impact of a nearly 0.18 of a standard deviation decrease in an aggregated measure of mental health problems among girls living in villages in the integrated arm and no impact (coefficient size ten times smaller at 0.018) among girls living in the girl only arm. The overall reduction reflects a decrease of 16 and 17% of a standard score, respectively, in depression and anxiety scores. Neither changed significantly among girls living in the girl only treatment villages where no community engagement activities took place.

- The programme had no significant impacts on life-skills including self-esteem, self-efficacy, peer relations, resilience and decision making strategies.

- The programme had no impacts on knowledge and attitudes to sexual and reproductive health.