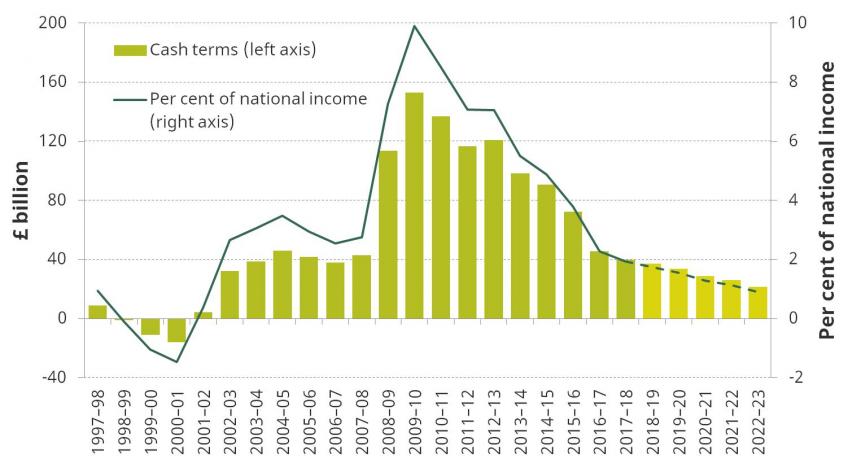

Chancellor Philip Hammond will present his Budget in a period of heightened uncertainty, with a deficit back to pre-crisis levels (see Figure) but a debt level that is much higher. He will have to balance commitments made to the NHS in the summer and the Prime Minister’s recent promise of an end to austerity with the government’s overarching fiscal objective – reaffirmed in last year’s general election manifesto – to eliminate the deficit entirely by the mid 2020s.

In this chapter, we set out the current state of the public finances, the outlook for the future, and some of the key economic and policy risks to the public finances in the medium and long term.

Key findings

- Borrowing has now returned to pre-crisis levels, and is lower than successive post-referendum forecasts. At £40 billion, or 1.9% of national income, the deficit in 2017–18 was the smallest annual borrowing figure since 2001–02. It was also over £18 billion lower than the OBR forecast in March 2017, and at a similar level to the last pre-referendum forecast in March 2016. This is not because the OBR’s economic forecasts were too gloomy in November 2016; rather, the public finances have proved more robust than expected given economic performance.

- Developments since March suggest that the outlook for borrowing has improved. Data from the first five months of 2018–19 suggest that borrowing this year might

be around £5 billion lower than the OBR’s forecast of £37 billion. By 2022–23, it might be around £6 billion lower than the OBR’s forecast of £21 billion.

- On the narrowest possible definition, ‘ending austerity’, as the Prime Minister has promised, would require the Chancellor to find £19 billion of additional public service spending relative to current plans by 2022–23. That would leave unprotected day-to-day departmental spending just constant in real terms, and falling as a share of national income. It would still leave in place £7 billion of further cuts to social security.

- Without much higher growth than forecast or substantial tax rises, ‘ending austerity’ is not compatible with eliminating the deficit by the mid 2020s.

- The deficit is down to pre-crisis levels, but debt is higher than it was by 50% of national income (over £1 trillion in today’s terms). Running a deficit of 1.8% of national income (as forecast for 2018–19) in ‘good times’ could easily leave debt on a rising path as a share of national income over the long term, while in the past it would have been consistent with projected debt falling fairly quickly. This is due to a combination of low growth forecasts and student loan accounting flattering the headline borrowing measure.

- There is a lot of uncertainty around any public finance forecast, but current levels of uncertainty are higher than usual. Based on historical forecast accuracy, the central forecast implies a one-in-three chance that the deficit will be eliminated in 2022–23, but a similar chance that the deficit in that year will rise from its current level. Brexit uncertainties raise the chances of the deficit turning out a lot different from forecast.

- We should worry that the Chancellor seems to treat forecast improvements and deteriorations differently. Evidence since 2010 suggests that Chancellors are more willing to spend windfall improvements than to enact a fiscal tightening when the forecast worsens. If this pattern of behaviour were to continue, this effect would push up the central forecast of the deficit in 2022–23 by £10 billion.

Figure. Public sector net borrowing since 1997–98