One of the most significant challenges facing the UK in a globalised world is the outcome of its June 2016 decision to leave the European Union. Brexit will have an enormous impact on the UK’s prospects for economic growth, so the continued uncertainty around what shape it will take makes forecasting the UK economy a very challenging exercise.

In line with most forecasters, we assume the EU and the UK will agree on a transition phase (likely lasting much longer than 21 months), during which not much would change for businesses and consumers. This long transition could potentially see UK growth continue or even accelerate due to pent-up demand. In the alternative scenario, where the UK leaves the EU without a deal, we would expect material economic disruption in the short term, not least due to a break-down of political cooperation between the two sides. But that would also be unlikely to be the end-state. The longer-run impacts of Brexit will depend on how the UK uses its new freedoms to make choices about regulation, trade rules and immigration systems.

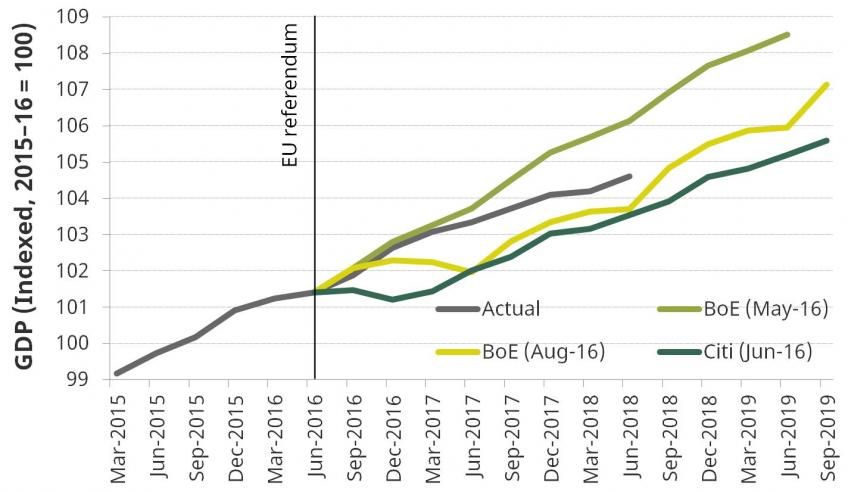

Amid all the uncertainty, the past two years have yielded a wealth of lessons about the UK economy. In particular, the big changes forecasters made to the UK economic projections around the EU referendum and how these forecasts played out provide lessons going forward. In this chapter, we provide an overview of the UK’s recent economic performance and compare it with our and other forecasters’ projections in 2016. We then present our current forecasts, based on our smooth-Brexit base case.

Key findings

- Post-EU-referendum forecasts were not very far off after all. Instead of a short-term hit and quick rebound, Brexit slowed growth more gradually. GDP in 2018 looks set to be only marginally higher than forecasters expected immediately after the referendum, and almost 2% lower than implied by pre-referendum forecasts predicated on a Remain vote.

- The UK economy has been somewhat supported by a strong eurozone economy. Contrary to immediate post-referendum forecasts, the eurozone economy appears to have been unaffected by Brexit uncertainty and continues to grow robustly.

- UK consumer spending held up better than expected in the wake of the referendum. However, that has been at the expense of a plunging household saving ratio. With saving rates at historic lows, the consumer might find it harder to ride to the rescue again in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

- A weakened currency, higher inflation, and lower business investment as a result of increased uncertainty have all hit UK growth. We estimate that the sterling depreciation in the wake of the referendum raised UK consumer prices by 1.7%. These outcomes are very much in line with most initial forecasts of the effect of the Brexit vote.

- Brexit is likely to weigh on growth for the foreseeable future. Most scenarios will see less free trade with Europe and lower immigration. This would result in lower growth. The scale of long-term effects will depend on how the UK uses any new freedoms. A more liberalised ‘global Brexit’ in which the UK is open to immigration and free trade will be less damaging to the economy in the long run, but more difficult in the short run, than a ‘drawbridge Brexit’ in which trade barriers are erected, protectionist policies implemented and immigration minimised.

- Our central assumption is that the UK and the EU agree on a transition period preserving essentially the same relationship they have today. This transition period will likely have to be extended beyond 2020 in order to facilitate the political calendar, detailed future trade negotiations and a ratification procedure that involves national and subnational governments across the continent.

- There is some reason for optimism about the UK economy. As the Brexit deadline approaches, investment and thus growth are likely to slow further (just as they did prior to the 2016 referendum). But after Brexit Day, there could be a growth rebound, before new uncertainty about the next Brexit cliff edge sets in.

Figure. Forecast and actual UK GDP (2015–16 = 100)