According to his Spring Statement speech, at this year’s forthcoming Budget the Chancellor will set a firm overall path for public spending for the years beyond 2019−20. At some point next year – perhaps in the Autumn 2019 Budget – this will be followed by a Spending Review to set detailed allocations for individual departments.

In the coming months, the Chancellor will therefore need to make a number of difficult choices. First, in setting the overall spending envelope, he will have to balance carefully any extra spending against the additional tax or borrowing required to fund it. He will then need to trade off spending on public services against spending on social security, and balance the competing demands of ministers and departments, to determine his priorities and set plans for the years ahead.

This chapter sets out the context for the choices facing the Chancellor, considers the necessary trade-offs and describes some of the possible implications for public service spending.

Key findings

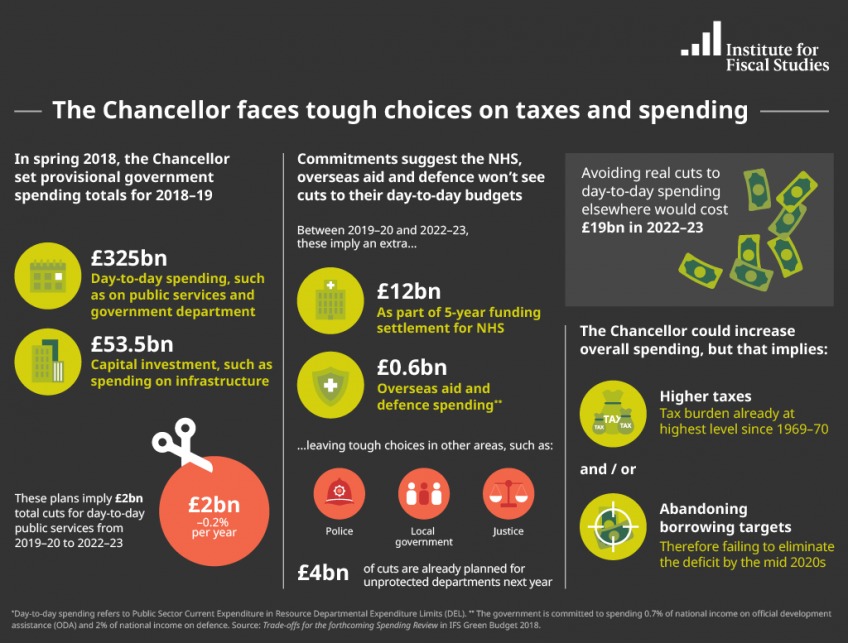

- The Chancellor faces extremely tough choices over next year’s Spending Review. Keeping to the provisional spending totals used in the Spring Statement would mean continued cuts for many areas of public service spending. But increasing spending relative to these provisional plans would push him further away from his target of eliminating the deficit by the mid 2020s unless taxes are increased or spending cut elsewhere.

- The government recently announced an increase in NHS spending of £20.5 billion over five years (£12.0 billion between 2019−20 and 2022−23). Existing commitments on overseas aid and defence also mean that day-to-day spending on these areas is expected to increase by £0.6 billion between 2019−20 and 2022−23, and a continuation of the existing agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) could entail an additional £0.3 billion a year of day-to-day funding for Northern Ireland.

- These commitments would imply cuts to other areas of day-to-day spending amounting to £14.8 billion in 2022−23 if the provisional spending totals from the Spring Statement are kept to.

- After eight years of cuts to spending on public services, making more would be extremely difficult. Increasing real earnings growth in the public sector also means future cuts to service spending would imply large reductions in government employment, after six years of relative stability.

- The Chancellor may well therefore decide to increase overall spending on services relative to the provisional totals set out in March. But doing so would require some combination of tax increases, higher borrowing and/or cuts to other spending, such as social security. None of these are easy options.

- The additional uncertainty over the form and effects of Brexit make these decisions and trade-offs even harder. Even ignoring the likely adverse effects of leaving the EU on economic growth and consequently tax revenues, there is likely to be virtually no ‘Brexit dividend’ over the next Spending Review period that could be diverted to fund public services. In 2022–23, net savings from contributions to the EU could be less than £1 billion a year, and higher UK administration costs – for customs, for example – could easily exceed this saving.