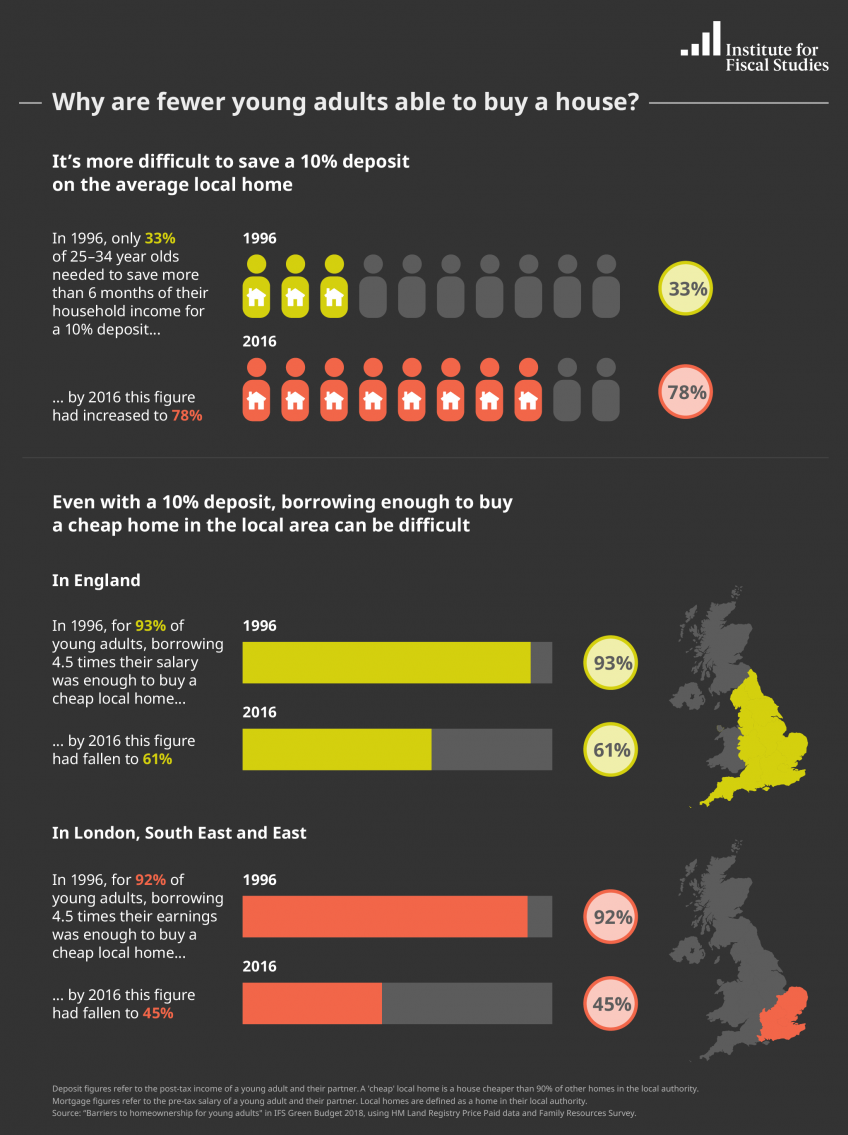

As long as they had a 10% deposit, in 1996 over 90% of 25- to 34-year-olds would have been able to purchase a house in their area if they borrowed 4½ times their salary (the maximum that most lenders will now allow). By 2016, that proportion had fallen substantially. Even with a 10% deposit, only around 60% of young adults would have been able to borrow enough to buy even one of the cheapest homes in their area.

Barriers to homeownership are particularly high in London where – even with a 10% deposit – only one-in-three young adults could borrow enough to purchase one of the cheapest homes in their local area. Back in 1996, if they had borrowed 4½ times their salary, 90% of young adults in London could have done so.

These are the headline findings of new research looking at young adults and the housing market in England, from researchers at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. This is available today as a pre-released chapter of the IFS Green Budget 2018, which will be published on Tuesday 16 October.

The analysis focuses on how barriers to homeownership have changed in the last 20 years and considers possible policy solutions. Other key findings from the chapter include:

- After adjusting for inflation, average house prices in England have risen by 173% since 1997, compared with increases in young adults’ real incomes of only 19%. Largely as a result, the share of 25- to 34-year-olds who own their own home fell from 55% to 35% between 1997 and 2017.

- The really big increases in house prices happened before the financial crisis. It is only in London, the South East and East of England that average real house prices are above their pre-crisis level. For these regions, real house prices grew by 30%, 8% and 10% respectively between 2007 and 2017.

- Rising property prices relative to incomes have made it increasingly hard for young adults to raise a deposit. In 2016, around half of young adults would have needed to save more than six months of their post-tax income to raise a 10% deposit on one of the cheapest properties in their area (their local authority), compared with just one-in-ten in 1996. To buy an average-priced home in their area, more than three-quarters of young adults would need a deposit worth six months’ income or more (up from one-third in 1996).

- House prices differ a lot more around the country than do young adults’ incomes. This makes it much harder for young adults in London to buy than it is for those in other parts of England. In London, 95% of young adults would need to save at least six months’ income for a 10% deposit on an average-priced home in their area. This compares with just over half in Yorkshire and the North East.

- For policymakers concerned by these trends, the key action is to increase supply of homes, and the responsiveness of supply to changes in demand. Planning restrictions, such as the Green Belt, prevent the construction of new homes in response to demand, particularly in London and the South East. Easing planning restrictions would increase homeownership and reduce both property prices and rents. Without increasing supply, policies to help young adults get onto the housing ladder will continue to push up house prices – and potentially rents too, which would hurt those (lower-income) young adults who will never be able to buy their own home.

Polly Simpson, a Research Economist at IFS and a co-author of the research, said,

“Big increases in house prices compared to incomes over the last two decades mean that it is increasingly difficult for young adults to get on the housing ladder, even if they do manage to save a 10% deposit. Many young adults cannot borrow enough to buy a cheap home in their area, let alone an average-priced one. These trends have increased inequality between older and younger generations, and within the younger generation too.”

Jonathan Cribb, a Senior Research Economist at IFS and co-author of the research, said,

“The most economically productive and wealthiest parts of England – London and the South East – are those with the most restrictive planning constraints. It is unsurprising that these areas have also experienced the biggest house price increases. Increasing the responsiveness of construction to house prices is a necessary part of the solution, particularly in these areas. Unlike other policy alternatives, this would both help reduce house prices, boost homeownership and reduce rents, benefiting renters, some of whom will never own.”