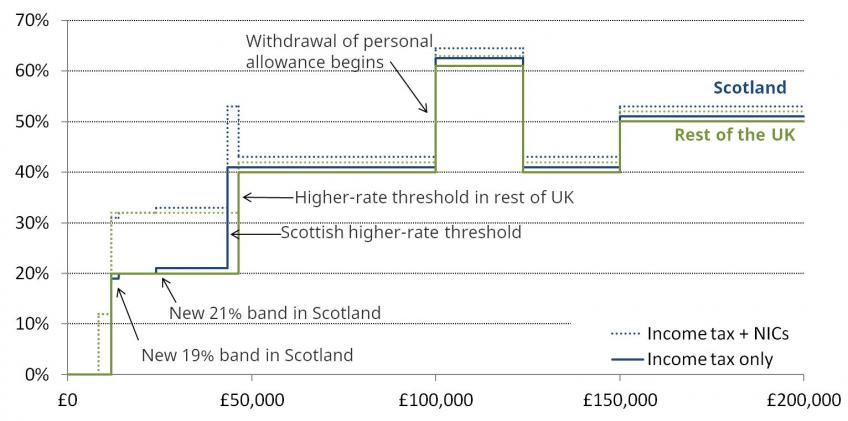

Today the now devolved income tax system in Scotland has diverged further from its counterpart in the rest of the UK. The threshold for the higher-rate of Scottish income tax (now 41%) was already below the threshold that applies in the rest of the UK and today increases by only 1% to £43,430, while the income tax thresholds that apply to the UK apart from Scotland have been uprated in line with inflation (3%). At the same time, there are two new rates (of 19% and 21%) within the basic rate band in Scotland, while the higher- and additional-rates have each been increased by 1% to 41% and 46% respectively (see Figure).

Figure. Marginal tax rate schedule on earned income, Scotland and the rest of the UK, 2018–19

Notes: Dashed lines include income tax, employee National Insurance contributions, and the withdrawal of the income tax personal allowance from £100,000. Assumes all earnings are from one job. The spike in the Scottish marginal tax rate at £43,430 reflects the higher-rate threshold for income tax in Scotland being lower than the upper earnings limit for National Insurance contributions (which is set for the UK by Westminster). Solid lines include only income tax and the withdrawal of the personal allowance.

In 2018–19, the Scottish income tax system will raise around £355 million more in revenue (3% of the Scottish income tax take) relative to what it would have raised had it retained the same system as the rest of the UK. Of this difference, the changes enacted this April are due to raise £225 million with a further £130 million a result of freezing the higher-rate threshold in 2017. Effectively, the Scottish government is utilising its tax-raising powers in order to reduce the squeeze on spending in Scotland.

Scotland chooses to raise more from top half of income tax payers

The effects of the tax changes vary across Scots. Table 1 shows the number of Scottish income tax payers in different earnings bands, and the difference in tax liability they will face in Scotland relative to the rest of the UK. (Note that technically the Scottish income tax system applies only to non-saving non-dividend income, which we henceforth refer to as earnings income.)

- 44% of Scottish adults do not have earnings above the personal allowance and so are unaffected by these changes.

- 31% of Scots – specifically, those earning between £11,850 and £26,000 – will pay less income tax in Scotland than the rest of the UK, although the gain is small (up to a maximum of £20 per year). The total giveaway to this group is forecast to be £23 million.

- 25% of Scots earn above £26,000 and will now pay more in Scotland than they would in the rest of the UK. In total, these individuals are forecast to pay £380 million more in tax, of which £250 million is a result of this April’s changes. Losses are greater for those with higher earnings. For example, an individual earning £28,354 per year (the median full-time earner in Scotland) will have a £24 higher tax liability in Scotland compared to the rest of the UK, while an individual earning £170,000 per year (enough to place them in the top 1% of UK income taxpayers) will have a tax liability over £2,000 higher in Scotland.

Table 1. Number of Scottish adults and difference in annual tax liability under the Scottish income tax system relative to that in the rest of the UK, by earnings range

Annual earnings | Number (000's) | Share (%) | Difference in tax liability |

£0-£11,849 | 1,990 | 44% | No change |

£11,850-£26,000 | 1,400 | 31% | £0-20 lower |

£26,001-£43,430 | 750 | 17% | £0-174 higher |

£43,431-£150,000 | 370 | 8% | £174-£1,943 higher |

£150,001+ | 20 | 0.5% | £1,943+ higher |

Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding. Population includes all individuals in Scotland aged 16+.

Sources: Authors’ calculations using HMRC, Income tax statistics and distributions, Office for Budget Responsibility Devolved Taxes Forecast, March 2018 and Office for National Statistics 2016-based National Population Projections.

Risks with the Scottish approach

While the changes represent a relatively broad-based tax rise, the concentration of losses among higher income taxpayers poses risks to the Scottish income tax yield. Previous work has shown that higher income individuals can be particularly responsive to tax increases. If no-one changed their behaviour in response, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimate that this April’s changes would raise around £320 million in 2022–23 (the final year of the forecast period). After accounting for likely behavioural responses, however, the forecast revenue gain falls by a quarter to £240 million.

One risk would be that these individuals migrate south of the border into England. While genuine migration is costly, it may be easier for those with multiple properties to change their tax residence within the UK. The OBR assumes no response in terms of genuine migration, but estimates that changes in reported tax residence as a result of this year’s changes will lead to revenue losses to the Scottish Government of around £20 million – almost 10% of the predicted yield. They note that an effect of this magnitude would require only a small number of additional rate taxpayers (fewer than 20) to switch their residence. This is because when a taxpayer relocates it is not just the additional tax revenue that the Scottish Government would lose, rather all of the income tax that they pay on their earnings would now go to the Westminster Government rather than Holyrood.

A risk to the UK wide income tax base is that of individuals incorporating – setting up their own company and paying themselves in tax advantaged dividends rather than salary. Growth in company owner-managers has outstripped growth in employees since at least the 1990s, and this is projected to continue, leading to a reduction in revenues of around £2.5 billion by 2021–22. While income tax on earnings is devolved to Scotland, dividend and corporation tax are set by Westminster. If an individual in Scotland incorporates, they not only pay less tax overall, but more of the tax they do pay is paid to Westminster rather than Holyrood. This means that (i) higher income tax rates make the incentive to incorporate stronger in Scotland and (ii) that Scottish revenues are particularly exposed to the risk of incorporation. If the rate of incorporation in Scotland outstrips that in the rest of the UK, Scottish income tax revenues would be depleted as a result (with no offsetting block grant adjustment).

The OBR forecasts explicitly take both of these behavioural responses – migration and incorporation – into account, though there is considerable uncertainty about the magnitude of their effect. While the OBR and Scottish Fiscal Commission estimate of the revenue from the latest changes are similar in 2018–19, the fiscal commission estimate in 2022–23 is 10% higher than the OBR’s (£267 million vs £240 million).

These behavioural responses are likely to be relatively moderate while the UK and Scottish income tax systems differ only slightly. But the ease with which individuals may be able to avoid higher taxes north of the border suggests that policymakers may wish to pause and consider the evidence of what happens in response to this small change before implementing any more radical departures.