Education is one of the most important predictors of people’s life chances. Better-educated people are more likely to be in work and tend to earn more. At the age of 40, the median university graduate earns roughly 80% more than the median non-graduate. And the influence of education doesn’t stop there. Education shapes a range of other outcomes, including health, criminality, and even happiness. That’s why explaining differences in educational attainment is essential to understanding lifetime inequalities.

Does everyone get the same start in school?

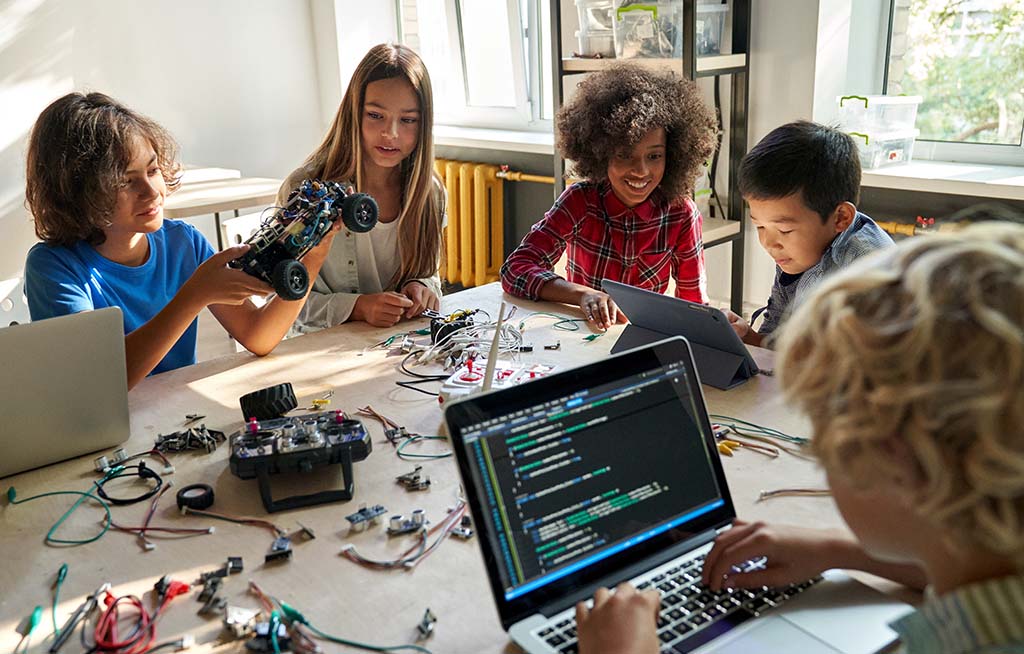

Inequalities in the education system start early. The UK, like most countries, requires children to attend school but the experiences children have at school can be very different. Where you go to school matters. In part because government decisions drive the level of funding available to different schools, but also schools make decisions as varied as whether to set children by ability or the size of classes. Teachers’ choices on how to lead their classes also have a huge impact on learning, and even the other pupils in a child’s classroom can influence their attainment.

These early inequalities matter because they’re so persistent. Among children who perform below the expected level at the end of primary school, only 8% go on to achieve a grade 4/C in both their English and Maths GCSEs. In our study we document when gaps in attainment emerge and how they evolve over the school years. We also investigate how these gaps are linked to characteristics like family background, gender, and ethnicity. As well as highlighting the existence of attainment gaps, we investigate how educational attainment is influenced by factors such as the school a child attends, their family, and their peers.

How do education inequalities develop beyond the school years?

After finishing compulsory education, people choose different educational pathways. Some students take the well-trodden academic track, completing A Levels and going on to university. Others enter the further education system, with a vast – and often confusing – set of qualifications to choose from. As part of our study, we ask how the UK’s post-compulsory education system affects existing attainment gaps. Does the current system allow the roughly 18% of students who don’t achieve five good GCSEs to get ‘back on track’?[1] Do the higher and further education systems provide the necessary training and qualifications to support young people in their future careers and help those who need to upskill later in life?

To answer these questions, we draw on robust research evidence and data analysis, as well as consider what the UK can learn from the education systems of other countries. Educational inequalities are nuanced and complex – but the Deaton Review provides comprehensive analysis that cuts across the whole of the education system to help us understand where the biggest challenges lie, and what we can do about them.