In this episode, we ask why is a high-tech, developed economy like the UK struggling to be more productive?

Paul Johnson

Hello and welcome to this edition of the IFS Zooms In, I’m Paul Johnson director of the IFS and I’m delighted to be joined today by John Van Reenen, he’s professor of economics at the London School of Economics and one of our leading thinkers on productivity and growth and, in the end, on what makes the economy tick. And I’m going to be talking to him today about exactly that, how do we get growth back into the economy, what’s happen to our productivity performance, why have earnings done so terribly badly over the last decade. And we’re going to get into a whole series of issues including education and investment, research and development and the big tech. But first, let’s start by asking about that productivity issue, what is productivity and why have we been doing so badly?

John Van Reenen

Well first off, I’m delighted to be here, Paul, and I’m very happy to share my thoughts on this area. Yeah, so there’s different definitions of productivity growth. Yeah, the simplest, kind of idea I think people would recognise is that it’s simply how much output you can get per unity of input. So, given all the effort you’re making to produce stuff, how much stuff can you make per unit of input? So, the simplest way and the most important input is people, so what I’d need to think about that, at kind of macro-economic level, would be output per hour works. So how much output do you get per hour worked, it’s sometimes-called labour productivity? And that’s the kind of, in a macro thing – you know micro-level you can kind of think about this as you know, cars per hour of work for a car factory, but if you think about the economy as a whole, it would be kind of output per worker.

Now a more sophisticated version would be where you take into account not just, you know, the workers, also how much you know capitol you put in, you know machinery, computers, buildings, other kinds of things. And if you took those into account, economists have this concept they sometimes call total factor productivity growth, which is taking out all the inputs. But the simplest way is labour productivity, that’s the most important, it’s just output per hour and how that changes over time. So, that’s kind of the notion of productivity.

Paul Johnson

And so, what do we know about why it stopped growing?

John Van Reenen

Well, I think no one really knows the whole story, I think no one’s come up with the complete story about why kind of productivity growth has been so lack-lustre in the UK. I think there’s lots of different factors going on. I think one thing, important thing to recognise, is that the slow down of productivity since the global financial crisis has been a global phenomenon. So, I think productivity growth has slowed down all over the world not just in the UK. So, in the US-

Paul Johnson

But more in the UK than elsewhere.

John Van Reenen

Yes. So, its fallen, the growth has been particularly bad in the UK. One factor is global, but of course it’s been particularly bad in the UK. Part of the story is, I guess, that there has, you know there was a kind of measurement kind of issue. So, it’s often hard to measure productivity and many people say well, parts of the economy that are growing, like the service sector is based on intangibles like intellectual property and software which is very hard to measure, so maybe we’re not picking up the growth, so I think part of it is that. But again, it can’t be the whole story, because as you said, you know, that’s true of everywhere in the world, it can’t just be true in the UK, although the UK has a bigger service sector and also has you know maybe more of theses sort of intangible assets.

A third factor is the, you know, the kind of big cut in demand that happened after the financial crisis, which also with austerity measures that we brought in meant there was quite a big cut of public investment in infrastructure, which happened a lot in the early part of the period. And so, the hangover of that kind of low demands in the UK, also, is a factor which pushed productivity growth down for a number of years. But again, that can explain some of the early part, it’s hard to think about why there’s this continuing drag on what’s happened in the kind of UK economy.

A fourth factor is, you know, the UK has done relatively well in employment. So, there’s more, you know relative to many European countries for example, unemployment recovered quite quickly, there’s a lot more people who are employed you know if those people are relatively less skilled with low productivity, that’s the drag down for our productivity levels.

Another factor is kind of investment, so investment has been relatively low in the UK relative to other countries, that’s a factor which is also pulling down productivity. So, there’s lots of these different factors but it’s like, none of them together give us the magic bullet of why things have looked quite as bad as they have. So, my personal view is that in some sense, you know, no matter how we got here, we should be thinking about how we get out of it. So regardless of all you know the reasons why we have had these problems, it’s a combination, I think, of demand size and supply side problems, the real question is to think about how we try and, you know, galvanise the economy to try and pull ourselves.

I mean one other factor I should say as well in more recent years, maybe the uncertainty which has come with the kind of Brexit vote, and you know that’s I think also had a kind of recent hit, so productivity investment and you know that’s another factor to be taken into account.

Paul Johnson

Well, the obvious question then is what is the Van Reenen cure of this dreadful productivity growth you’ve just described? Whatever, as you say, whatever the reason, they key is to do something about it. And you know just so that listeners kind of keep listening, I mean there is nothing more important than this, because if we are to see earnings and incomes rise again, at any kind of reasonable pace over the medium run, we’re going to have to get productivity moving in a way that it just hasn’t done for more than a decade now. So, what’s the answer?

John Van Reenen

Well, you know I think part of the diagnosis of the problem the UK has been we have failed to, you know, make long run investments in kind of key things which have been found to be major drives of productivity. So, I think the big failures that we’ve had is in inadequate innovation, so you know research and development and other things which could be good for the coming up with new ideas; inadequate investments in some types of human capital and people; and inadequate investment in infrastructure. So, I think that the set of things to be thought about, is how can we get the ability to deliver sustained growth of those long run type of investments.

And you know, I think part of the problem actually is a political problem, but the kind of British political system is a lot of churning and rebranding of policies and short time horizons, and you know institutionally, you know, you can think there reforms which can somehow overcome some of the problems which would cause this would be, you know, an ability to commit to making these type of investments. So, there’s a kind of policy type of problem.

But going through those things, you know there’s a lot of different elements to this, so one is like if you look at research and developments, Britain has relatively low levels of research and development, compared to other countries so you know we’re very good at, we’re very good at the elites, so we have the top universities we kind of come out with you know an amazing amount of scientific papers, so at some elements we’re very strong, but where we need to be less good is actually converting those ideas into commercialise innovations. And that’s where kind of the you know the R&D element comes into that. So, I think there’s a lot of ways in which we can kind of boost our R&D spend, encourage different types of investment, innovation. I’d also say, you know, we should think of innovation in a wider sense, it’s not just the kind of hard technologies, some of those innovations are managerial innovations and so you know a lot of my work has been thinking about how management practices can be improved, and you know that also requires both things like investment in training, investment in improving managerial practices.

So that’s one, human capital is the second one and I know you’ve written about his Paul as well, I think that, again, at the top end we’re very good, but where we really seem to fail a lot of kids in in, kids who are not going to university necessarily but you know are still, you know, can still do with the kind of skills that you need in order to be successful in the workforce. And those intermediate skills were very, we seem to be very poor at around further education and apprenticeships and so on. So, I think that there is a big gap there that needs to be improved dramatically if we want to both address some of the issues of inequality but also to deal with the kind of productivity problems.

And finally in infrastructure, you know it’s a well-known problems that, around you know transport and energy, has been underinvestment over a number of years. And we need to think about you know sets of institutions in order to kind of deliver a sustainable infrastructure, so I kind of welcome some of the changes the governments made in terms of thinking about the infrastructure bank and the infrastructure commission. You know going back to my point about the policy reversals and uncertainty, you know what we’d like to do, and I did this LSE growth commission a few years ago, with Tim Besley, think about creating institutions that have some degree of political shielding from the kind of day-to-day hurly-burly of policy so we can use experts, inputs, you can, you know, get some independence in making these type of decisions. And we’ve seen it works in many other contexts like Bank of England and the Office of Budget Responsibility. If we can have more of that in terms of our kind of infrastructure decisions and investments this can also help. So those are the kind three areas I would kind of emphasise in terms of improving our kind of long run productivity problems.

Paul Johnson

And it is interesting what you say about the political problems here, because if I, my guess is you know if I’d asked your, one of your predecessors at the LSE the same question fifty years ago, they might well have come up with a very similar kind of answer. Now you know the world has changed a lot since then, we do have many, many more people going through higher education, and so on, but the general issue for the UK of that lack of sort of good technical education and that lack of infrastructure and that difficulty translating that top research into commercialisation, commercialisable developments, something that’s incredibly long standing, isn’t it?

John Van Reenen

It is, I mean you know, there are areas of like, on education I mean there have been successes. One of the positive things, I mean it’s easy to fall into despondency sometimes, over these things, you know especially when you think about difficulty of getting experts, opinion, advice in terms of, over things like Brexit and so on, but I think you know one thing to remember is that, for that thirty years leading up to the global financial crisis, there was an improvement in Britain’s relative productivity performance, and relative economic performance compared to France, Germany, the United States. So, we had a hundred years of relative economic decline, and you know the 1870s to 1970s. So, although you know compared to say many European countries and the United States, everybody grew, Britain grew less. Now part of that was catch up but a part of it was genuine relative decline. But then there was you know thirty years of relative improvement. And you know part of that was lots of reasons, under Thatcher, under Blair, structural strength and competition but also there was big investments and improvements, of expansion of universities, I think that was a, you know that increases of human capital at the top end was beneficial to productivity.

That’s part of the story. But I think what that left out was the other half or you know of the population who are not going to university and were not getting the same type of access to those skills. You know, that I think as you say, that’s a long-standing problem. But the fact there were improvements to productivity, there have been periods in which the UK has you know caught up with some of its peer counties suggests policy can make a difference, it’s not a hopeless situation. But it is true, many of these things we’re talking about have, you know, refrains throughout British history.

Again, not always, you know, we were the first industrial nation, you know massive changes to the investments we made in terms of electrification in the second industrial revolution, so you know there is a history there to be drawn on. But there are these kinds of long-standing problems as well.

Paul Johnson

And I’m completely with you in terms of believing in the power of policy to change things, I think part of the problem is that that power to change things is something that happens over a protracted period, it’s very difficult to do it within the electoral cycle. So, if you’re changing competition more, if you’re changing vocational education structures and so on, you’re going to reap the rewards of that, ten or twenty years down the road, not in the three for four years between now and the next election.

John Van Reenen

That is exactly, I think that is the precise political problem that you know for many things that doesn’t matter so much, you know there are things you can change quickly and have, you know, quick successes. But the things like productivity, the rewards are in the long run, and you know its outside the usual political time horizon of prime ministers, let alone ministers who cycle you know in and out in often two years or eighteen-month period. So, I think that though it’s that, you know, somehow, can we make institutional changes which kind of buy politicians time, as it were? So, they can you know, it kind of puts some grit in the wheel of trying to medially change a policy that your predecessor had, and you have to say you don’t want to do it because you’re doing something different, or you have to rebrand it in some ways. I mean at least an example would be industrial, you know there’s lots of problems with industrial policy, industrial strategy, but it did seem to me that we were getting some stability in thinking through you know what modern industrial strategy should mean, we had sort of institutions which were set up, and now we just abolish them. You know without much discussion or thought, and all the kind of you know human and physical intellectual capital which was built up over that has just you know, not totally been destroyed but certainly being dispersed without really much thought it seems.

Paul Johnson

You’re referring to the abolition of The Industrial Strategy Council, wasn’t it?

John Van Reenen

Yes, and everything around that has you know, so that’s an example of things, yeah.

Paul Johnson

Yeah, I mean the number of examples I can think of, of strategies and bodies and directions of travels, particularly actually in vocational and technical education over the last twenty, twenty-five years I’ve been involved in it, is every five or six years we seem to completely start from scratch again. But you mentioned when you answered a previous question, John, you talked about the sort of Britain’s forefront of industrial revolution, and you talked about the second industrial revolution and electrisation and so on. I think one do the things that really puzzles people about, you know the current period is that we appear to be going through a third industrial revolution, you know we’ve got the internet, iPhones and you know what we’re doing, we’re over Zoom at the moment, something unimaginable really not very long ago. We’ve got sort of these fantastically successful companies like Google and Amazon and so on, you’d think that our living standards would be going through the roof at the moment, I mean what’s going on there?

John Van Reenen

Yeah, it’s a big puzzle at one level because yeah, we see all these amazing innovations, yet we don’t see them in the productivity numbers. But there’s history to this, so you know my former colleague at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Paul Solo, he famously quit, you know we see computers everywhere apart from the productivity numbers, and he was writing this in the 1980s where you had like you know massive growth of personal computers, everything else, but you didn’t see them in the productivity numbers. But then you did, so you know from the mid-1990s you know around about 1995 to 2004 in the US there was the so called productivity miracle period where there was a big jump of productivity and you know that was built partly on the success of digital transformation and the internet and so on, and I think you know, there’s some lessons from that for today, you know the new technologies, artificial intelligence, robotics, and everything else. I think, so part of it is that people are still learning how best to use these technologies. So, many of these technologies, and you mentioned electrification, there’s a famous paper by the historian Paul David who shows you, you know, between the kind of invention of electricity and the, I think it was the 1890s and the you know the way that boosted productivity, it too a whole reorganisation of the factory system, so people had to learn to you know, you could run factories twenty four hours a day using electric lights, you could you know later on you could think about a more kind of production line type of system, you know that Henry Ford introduced. So, it took these organisational innovations to make best use of the new technologies which were created in ways which people hadn’t thought. So, I think that the lesson is that it’s often, it often needs this kind of co-invention of changing the way that we work together with the kind of hard technologies to get the kind of productivity benefits from it, not just the kind of light bulb idea, literally, from electricity, it’s also the way that that actually gets used and changed. Now maybe when we’re living through the pandemic this will be a moment when we actually start using some of these technologies in ways that we weren’t imagining before. So, I think part of the story is that you know there are these other changings that we need to make and work organisation to make best use of the new technologies.

Another part of it is that we were talking about before is that we’re maybe not measuring the benefits you know, so a lot of these things are free, like you know when you search on Google and so on, it’s not reflected really in GDP figures. So, part of it might be measurement. But part of it might be also to do with, well I guess a part of it might be, you know, these are not such fantastic - the fact you can go on Facebook and find out your old girlfriends from when you were in school, isn’t actually wonderful for productivity, it might be good for your utility or maybe-

Paul Johnson

Looking into the secrets of your private life here, John!

John Van Reenen

But you know, some of these, so Bob Gordon who’s an economist in the US, you know there’s to be nothing, none of the new things that we’ve had have been as good as indoor plumbing. Indoor plumbing was fantastic, looking up your ex-girlfriends on Facebook is not so great, that’s the - but the other thing maybe is that there are problems with big tech, so one of the facts that we’ve seen is that so much of the digital economy is dominated by a few very large firms. Mainly, you know clearly there’s lots of innovations going on and they’ve built new things that we could not have imagined before, you know Amazon is bringing us you know goods to our door every day, and it’s amazing just in time delivery and you know Facebook is connecting us. But they have a lot of market power. And you know that potential lack of competition and the dominance of many of the digital markets by few very large firms, may actually be having some negative side effects.

So, you know for example, a lot of growth often comes from new start-ups companies and new business being able to grow. Maybe the power of some of these large firms is actually you know, making it harder for these new start-ups to enter and grow to the scale they have. For example, you know these large companies, Google and Facebook often buy up promising start-ups, and then absorb them into themselves, and they see this as good because we’re looking these things to grow and we’re using our own financial muscle and intellectual muscle. On the other hands, maybe they would have grown up to be more innovative and be threats to these dominant firms. So, you know if you can’t kind of kill them off, you buy them up. And that is a, I think that’s a real concern that although these firms have managed to you know get where they are partly through their innovations, now they’re in such a powerful position, they maybe chilling some of the innovations of other companies. So, I think we need to kind free thinking, you know anti-trust, you know competition policy in this new kind of digital age that we live in.

Paul Johnson

So, part of your answer to the question how should we be improving productivity and living standards over the next several years, is actually changing the way that we think about regulating some of these big tech companies?

John Van Reenen

I do, I do think we need to modernise our whole you know competition policy; you know we, there are lots of positive developments I think you know in the UK in terms of toughening up competition policy, one of the, you know, strongest findings I think in the empirical literature, in looking at productivity is that competition could be a very strong force to improving productivity. You know both because it has a kind of ruthless Darwinian effect of weeding out the low productivity firms enabling the more productivity firms to expand. But also, you know, by incentivising managers to work harder, and if you’re like a monopoly you can sit back and have an easy like, if you’re facing competition you’ve got to really get your act together. So, competitions really important.

But the traditional way that like for example we judge should two firms be allowed to merge together, or should a big firm be allowed to take over a small firm, we say, well, what’s their market share, you know if they’ve both go you know big market shares, they join up the monopoly, we don’t let that happen, but you know if one firm has a very small market share, then you know we might be relaxed about it. And that’s fine in the old economy, but in the you know in the kind of economy we’re in now, it’s really about you know future competition. So, when Facebook for example took over WhatsApp or Instagram, they were pretty small companies at the time, but if they were allowed to develop on their own, they may have become you know pretty big platforms, big competitors to Facebook. And so, you know these things got waved through by the competition authorities, but you know I think in retrospect, I think that was a mistake. Because you know once they became part of the larger company they no longer, you know kind of developed as independent competitors. So, I think we need it have a much more future looking competition policy, and we need to be concerned you know how these forums could have developed, these new platforms could have developed to become future competitors.

Now what the, of course the problem with at it is very difficult to know, how do we know whether one firms is going to become successful or not, but I think at the moment the burden of proof is all on the kind of government, so the government, this is not just true in the UK but it’s true in the US, the government has to show almost without a shred of doubt that these firms would have become you know competitors in the future, if you can’t show that, then you know you can’t block the merger. But I think we have to put more of the burden of proof back on the companies to say, “well okay, you’re telling us that these companies wouldn’t have thrived without you, you know what evidence can you bring to bear on that?” So, I think that somehow the, you know shifting that burden of proof may actually make it harder for these large tech firms to kind of entrench their kind of positions. So, I think that’s an example that I think more broadly, thinking of more a kind of, a further kind of model of competition. And to be honest you know; the UK Competition and Markets Authority is starting to think in these ways. So, they’ve set up you know new digital markets to kind of look at the digital sector to try and think of different ways in which these barriers to entry for new companies can be reduced, to put more responsibilities on these larger firms, potentially. So, you know reduce the risk that they kind of, kind of throttle off potential competition. So, things are moving in the right direction, there’s lots of thinking, but we still need those to actually take place to actually future proof competition.

Paul Johnson

But, I mean it’s taking a while, isn’t it, I mean we’ve had these sorts of big companies around for you know, they didn’t just arrive yesterday. But the, is there something that we the UK, or the UK CMA can do much about? You know what we’re, I mean when we think about these big monopolies, I mean we’re mainly thinking about the enormous US companies, whether it be Google or Amazon or Facebook. I mean are we not pretty much at the mercy of the decision that are made in the US?

John Van Reenen

Well, you’re right that these are mainly US based companies but I don’t think, you know individual countries are you know are completely weak and hopeless to do anything. So, you know it’s absolutely right that you know the main changes has to be with the biggest blocks, which is the US and the European Union. But take the European Union, you know the European Union has a common competition policy you know violations of competition law can be punished by 10% of the annual turnover of these companies. So, there is a strong threat which can be made again these companies if they violate some of the competition guidelines. So even though these companies are based in the US, they get a good amount of their profits say from Europe from the European Union, and so that gives the EU a lot of you know clout. Now the UK is smaller, its outside the EU, so there’s less clout, but we’re not insignificant. So, you know an example would be in Australia, there was this recent change over the ability of I think social media platforms like Facebook to use publishing material content from other companies, and Australia bought a law. Now of course, Facebook pushed back against that, but even a small country like Australia, could do something in order to challenge some of the activities of the large companies were doing. So, I don’t think even for a community like the UK, we’re without any influence.

I think that also there’s a, you know a sense in which you know, the UK can kind be a leader and try to think some of these things through. And so, you know there was the Furman Report, Jason Furman who’s an American economist, he used to be the chief economist under President Obama, he worked with the CMA to produce a report exactly on this and his recommendations, so the committee’s recommendations were adopted. And that thinking has now also affected the thinking of the European Union and is people in the United States as well. So, the UK can actually you know help be a leader, potentially in thinking though some of these issues, and trying some of them out. So, I don’t think we should overestimate our power, we’re clearly you know a small country. But you know I think we’re not powerless and I think especially if we can have some more cooperation with competition authorities in other countries, you know we can certainly make a difference.

Paul Johnson

Well, we’ve covered a lot of ground then, starting off with this question about this collapse in productivity growth, particularly over the last decade, which we don’t fully understand, particularly in the context of the technical revolution that’s been going on. But there are some pretty clear, at least high level policy, there are pretty clear high level policy agenda of the future to as it were, save us from this slough of lack of growth and productivity and earnings and living standards, which centre around I think three sets of investments you were talking about, research and development, infrastructure, and human capital - skills and education and so on, along side a focus on our institutional structure and this regulation of big tech. I mean within that, I mean presumably, you put all of that together, and that would be sort of the, you know that would be the core of the Van Reenem industrial strategy, the growth strategy for the UK?

John Van Reenen

Yes, I think that that’s what I’ve argued for. I mean we can go into some more details, I think one other thought to plant in listeners mind is that you know inequality is a massive issue in the world and in our country, if we can think of policies which you know, both tackle growth but also have you know a positive effect on reducing inequality, those are the kind of policy win-wins. So, one idea you know people think about inequality of education as just about you know equity, which of course it is. But we’ve shown in the context of the US work, you know there’s a huge loss of talent that many of the people that would have become great inventors, we call these the lost Einstein effect. Many of the people who could have become potential great inventors, don’t have the opportunity because they happen to be born in the wrong place, don’t get access to education, don’t get exposure to being an inventor. And in the US for example we think you could maybe quadruple the innovation rates if you could reduce those inequalities. I think the same is probably true in the UK. So, if you could think about things, of educational interventions which deal with disadvantage you could both try to tackle inequality but also improve growth by unlocking some of the lost talent that we have. So, I think in terms of thinking about policies you know often these policies can go together to tackle inequality and loss of growth.

Paul Johnson

Well, I mean we could go into a lot more detail in all of those areas John, and actually maybe we should talk again some time to delve in depth in one of those particular areas, but I think we are probably way past our time today. But that was just a fascinating I mean really fascinating conversation covering a whole range of areas and really getting at, you know the most important things facing us over the next several years which you know have been interrupted by COVID, and by Brexit and all of these things, but actually the underlying issues are pretty well understood, and the underlying problems are pretty well understood. And I think I really do take away from what you’re saying John that in a sense the real sort of underlying, underlying issue is about our political institutions and the real difficulties we have of pushing through in a consistent way to achieve the sorts of things that we’ve been talking about today. So, the challenge I think for the, you know it’s simply to completely reform the British constitution in order to make-

John Van Reenen

And the class system as well while were at it.

Paul Johnson

And the class system while we’re at it. So, there’s a small set of challenges to leave you with. But thank you so much John, thank you everyone for listening. If you want to see more of the IFS’s work, including some of the work for the Deaton Review, which John is involved in, do go to our website www.ifs.org.uk and to further support out work consider becoming a supporter of the IFS for just five ponds a month. You can find the link with further information in the episode description. Thank you for listening and stay well.

Listen now: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Soundcloud | Acast | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | RSS

In the past decade, the UK has seen some of the slowest rates of productivity growth of the OECD countries, with output per hour and real wages no higher today than they were prior to the global financial crisis.

Why is a high-tech, developed economy like the UK struggling to be more productive? What policies can government implement to get productivity growing again? And how can we spur innovation while also tackling issues like inequality?

This week, we speak to John Van Reenen, Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics, and expert on innovation, firms and productivity.

Zooming In: discussion questions

Every episode, we share a set of questions designed for A Level economics students to discuss, written by teacher Will Haines.

- How do economists define productivity?

- What factors can explain the poor productivity growth in the UK since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis?

- What role has technology played in the productivity puzzle?

Host

Director

Paul has been the Director of the IFS since 2011. He is also currently visiting professor in the Department of Economics at University College London.

Participants

John Van Reenen

Podcast details

- Publisher

- IFS

More from IFS

Understand this issue

Spring Budget 2024: What you need to know

7 March 2024

Should we worry about government debt?

11 April 2024

The NHS waiting list: when will it come down?

29 February 2024

Policy analysis

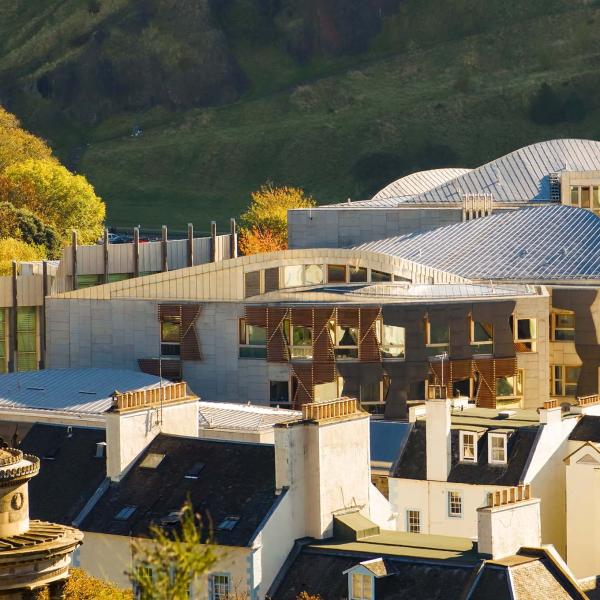

The IFS Scottish Budget Report – 2024–25

22 February 2024

How has the NLW affected pay differentials within firms?

16 February 2024

Scottish NHS is treating fewer patients than pre-pandemic, despite big increases in staffing

9 February 2024

Academic research

The role of privately held firms in income inequality

29 November 2023

Mafia infiltrations in times of crisis: Evidence from the Covid-19 shock

9 October 2023

Firm concentration & job design: the case of schedule flexible work arrangements

6 April 2023