This week saw major announcements on health and social care funding. Outside of the usual Budget or Spending Review process, the government announced around £12 billion of additional spending for the Department of Health and Social Care for each year between 2022−23 and 2024−25, alongside a corresponding tax rise.

In the near term, the bulk of this additional spending is earmarked for the health service, to aid with recovery from the pandemic. But in the medium term, most of this virus-related health spending is (more or less) assumed to fall away, as the NHS reverts to its pre-pandemic spending path. Under the funding settlement which pre-dated the pandemic, NHS England funding was planned to grow at an average real annual rate of 3.9% over the five years between 2018−19 and 2023−24. This week, the government extended the settlement by a year. Over the six-year period from 2018−19 to 2024−25, funding is still set to grow at an average real annual rate of 3.9%. That would suggest an extension of the long-term plan, and thus a similar amount of NHS funding to what might have been expected pre-Covid. This implies minimal additional virus-related spending on the NHS after that point.

Instead, the plan seems to be for the £12 billion raised from the tax rise to be increasingly channelled into social care as the parliament goes on, to meet the growing costs of the government’s new ‘cap and floor’ plan for social care funding. But that would require the government to stick to these NHS spending totals – something which history teaches us is unlikely. Instead, the experience of the past 40 years shows that NHS spending plans are almost always topped up. If history repeats itself, the ‘temporary’ increases in NHS funding announced this week could end up permanently swallowing up the money raised by the tax rise.

A history lesson

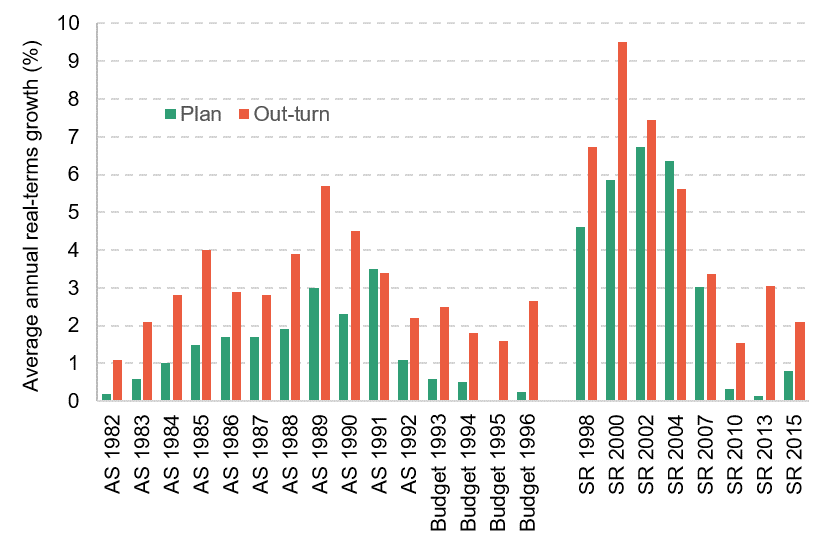

Figure 1 compares the planned growth rate in health spending to what actually happened (the out-turn), starting at the 1982 Autumn Statement, and finishing at the 2015 Spending Review (which covered the period up to 2019−20). On only two occasions over that period of almost 40 years has health spending grown by less than was originally planned; it almost always grows by more. This isn’t because the NHS is always overspending its final budget – it’s because the NHS budget is frequently topped up. This Figure also ignores the exceptional case of the 2019 Spending Review, which planned for 3.1% real terms growth in the health budget in 2020−21. In the event, because of Covid-19, it grew by more than 27%.

Figure 1. Health spending plans and out-turns

Note: AS denotes Autumn Statement; SR denotes Spending Review. Figures refer to average annual real-terms percentage growth over the planning period (typically three years from 1998 onwards). For example, SR 1998 covered 1999−00, 2000−01 and 2001−02. Planned real growth rates are based on contemporaneous forecasts for the GDP deflator; out-turns use the June 2021 deflator series. SR 2019 out-turn figure includes Covid-19 spending in 2020−21. Deviations from plan can therefore represent differences in spending levels, inflation forecast errors, or both.

Source: Author’s calculations using HM Treasury Budgets, Autumn Statements, Spending Reviews and Public Expenditure Analyses (various), with figures for AS 1982 to Budget 1995 taken from IFS Election Briefing 1997.

Between 1982 and the start of the pandemic, keeping to initial real-terms spending plans would have meant health spending growing at an average rate of 2.7% per year. But on average, it grew by 4.1% per year: 1.4 percentage points, or 53%, faster than planned a year previously (Table 1). (If you include Spending Review 2019 plans for 2020−21, the average difference between planned and out-turn growth grows to 2.0 percentage points, or 74% faster than originally planned, due to the huge sums spent on the response to Covid-19.)

Table 1. Health spending plans and out-turns since 1983−84

| Excluding Covid-19 | Including Covid-19 |

Average planned real-terms growth rate (%) | 2.7 | 2.7 |

Average out-turn real-terms growth rate (%) | 4.1 | 4.7 |

Average difference (percentage point) | +1.4ppt | +2.0ppt |

Average difference (as % of planned rate) | +53% | +74% |

Note: All averages are weighted for the duration of the plans in question (e.g. the planned growth rate at a three-year Spending Review is given thrice the weight of a one-year Spending Review). Figures excluding Covid-19 are for 1983−84 (covered by Autumn Statement 1982) to 2019−20 (the final year covered by Spending Review 2015). Figures including Covid-19 also include 2020−21. Source: as for Figure 1.

What does this mean for the Chancellor’s latest announcement?

Following the government’s latest announcement, the NHS England budget is set to grow between 2018−19 and 2024−25 by the equivalent of 3.9% per year in real-terms. What might happen if history repeats itself, and the NHS budget grows even faster than planned? For illustration, assume that NHS budget instead grows by 5.3% in real-terms between now and 2024−25 (the 3.9% medium-run planned growth rate, plus the average absolute difference of 1.4% from Table 1). That would mean spending an additional £5 billion on the NHS by the end of the parliament, on top of the more generous plans announced by the Chancellor this week. A top-up on anything approaching that scale could easily eat into the amount available for social care.

As an aside, it is worth noting that even without any top up, health spending is set to account for an ever-growing share of total day-to-day public service spending: 44% by 2024−25, up from 42% in 2019−20, 32% in 2009−10, and 27% in 1999−00.

Of course, this time could be different. The Treasury has provided the NHS with a relatively generous settlement, and has announced a manifesto-busting tax rise in order to do so. This time, the totals may be stuck to. With a multi-year settlement, the NHS may be able to plan and spend funds more effectively, improving health system performance and removing the need for any future top-up. Maybe. But the experience of the past 40 years is that this new, shiny set of NHS spending plans should be viewed as a lower bound, not a firm set of limits.

This analysis was funded by the Nuffield Foundation as an early output of the 2021 IFS Green Budget.

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance educational opportunity and social well-being. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare and Justice. It also provides opportunities for young people to develop skills and confidence in science and research. The Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory and the Ada Lovelace Institute. www.nuffieldfoundation.org | @NuffieldFound