In a bid to become the next prime minister, both Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt say they plan to increase the point at which people start paying National Insurance Contributions (NICs). This move would make the UK’s tax system even more different to those in most other developed countries in two ways.

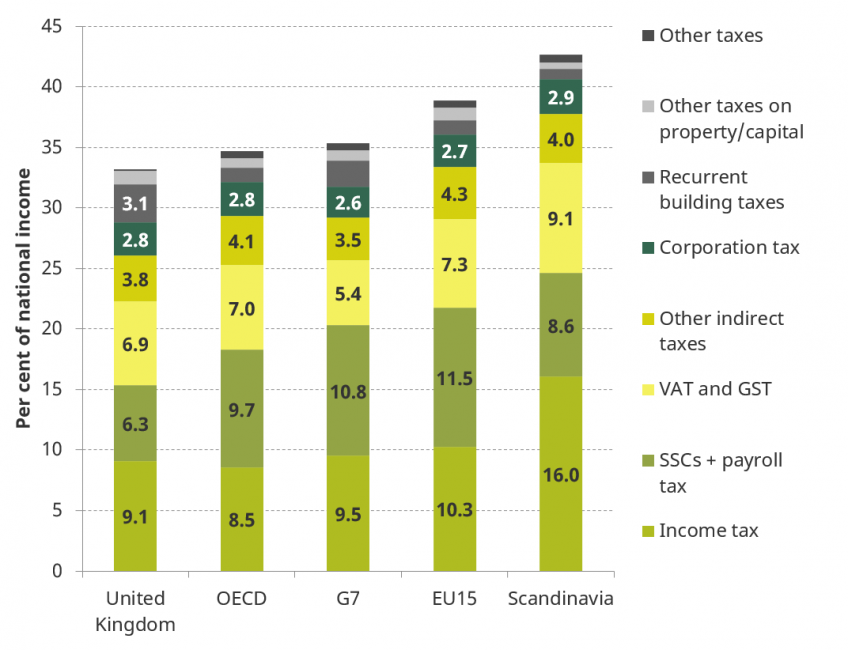

First, the UK already stands out in raising a lower share of overall tax revenue from income taxes and social security contributions (i.e. NICs and other countries’ equivalents). In fact, lower revenues from these two taxes entirely explain why total tax revenue as a share of national income is lower in the UK than on average across other developed countries.

Tax revenues as a share of national income, 2016

Note: SSCs is social security contributions. VAT is value added tax. GST is general sales tax. Source: Figure 3, How do other countries raise more in tax than the UK?

UK imposes lower taxes on middle earners than higher tax countries

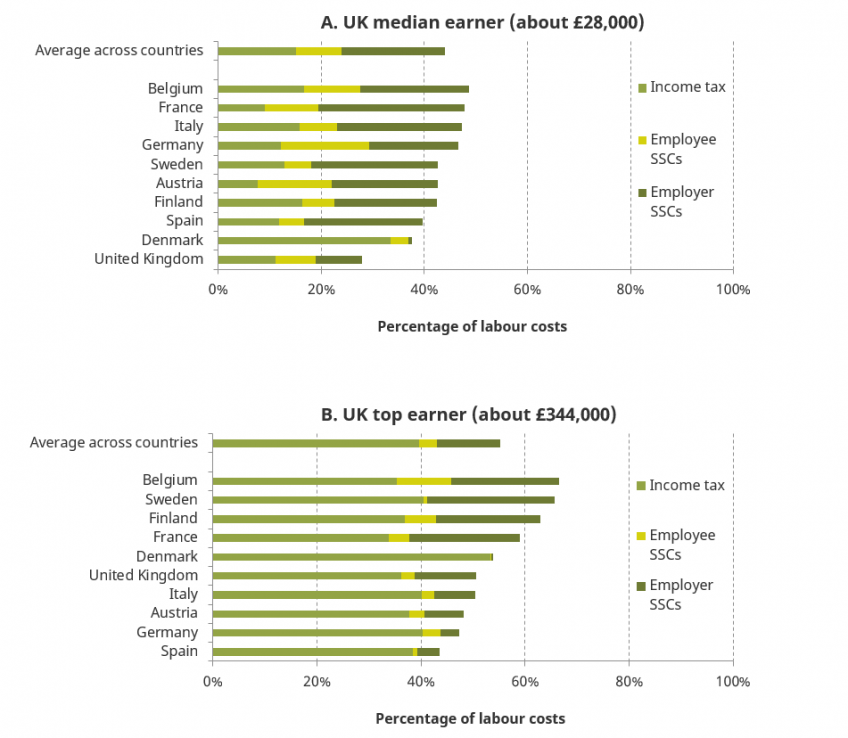

Second, new IFS research shows that the UK stands out most in its relatively light taxation of median earners’ incomes, especially for social security contributions.

For someone earning £28,000, which is enough to put them in the middle of the UK earnings distribution, HMRC will collect almost £3,000 in employer NICs and nearly £6,000 in income tax and employee NICs. Overall, this means that about 28% of what it costs to employ a person on median earnings (£31,000) is taken in income tax and NICs. This rate would be substantially higher in many other European countries. For example, if the UK imported the French tax system, not 28% but 48% of the cost of employing someone on £28,000 would be paid in tax. That would mean an extra £10,000 in tax revenue – more than double the current amount – for each person employed on median earnings.

Average tax rates rise as earnings rise. A bit more than half (51%) of the cost of employing someone earning £340,000 – that’s ten times average UK earnings – ends up in the hands of the taxman. This rate would rise to 59% if the UK imported the French tax system and 67% if it imported the Belgian tax system. Moving to 67% would equate to an extra £91,000 in tax revenue for every higher earner.

The figure shows that the average tax rates faced by UK top earners are more similar to those in other countries than the rates faced by median earners. This means that if we imported the tax system of one of the European countries that raises more tax overall, average rates would rise for high earners, but they would rise by even more for middle earners.

A large part of the difference in social security contributions across countries arises from employer contributions. That is, if the UK were to implement a system more like one of the higher tax EU countries, it would imply higher contributions from both employees and employers. While the former would be felt directly by individuals, we would expect higher employer NICs to affect the wages employers were willing to offer.

Important choices about level of tax and who pays

UK tax revenues are currently at their highest share of national income since the late 1960s. For many, this historical context paired with a desire to boost the economy after Brexit, will suggest that now is a good time for tax cuts. But an ageing society is increasing pressure on health, social care and pensions such that even maintaining the current quality and scope of public services will likely require higher taxes in future. Whatever decisions we make on tax, they must be linked to discussions about the level and kind of public services we want and how to share the bill for paying for them.

Other countries show that it is possible to operate successfully with much higher levels of tax. They achieve this not only by raising more from the very rich but also by having higher income taxes on middle earners. There are good reasons why the UK may want to make different choices about what and who to tax. But taking people out of income taxes altogether and reducing them on median earners (as has been the case with increases in the personal allowance and would be the case with increases in the starting point of NICs) can get very expensive very quickly.

A government wishing to cut income taxes and make up the revenue elsewhere could look to one of the other ways in which our tax system stands out internationally. The UK’s VAT raises about the same share of tax revenue as in other developed countries but from a much narrower base. Rather than focus on how leaving the EU would allow us to add more preferential rates into our VAT, we could take steps to remove some or all of the zero and reduced rates , which together cost £53 billion each year. Such policies are often supported as a way to help those on lower incomes but they are poorly targeted. The revenue raised from a broader VAT base (i.e. one with fewer reduced rates) could be used to fund income tax and benefit measures that are better targeted at helping those on low incomes and have revenue left over.

Average income tax and SSCs rates

Note: Average tax rates are calculated as the sum of income tax, employer SSCs and employee SSCs paid as a share of labour costs (earnings and employer SSCs paid). The average excludes the UK. The figures are based on the taxes applied to single people without children, but the patterns are similar for households with children. Source: Figure 9, How do other countries raise more in tax than the UK?