Summary

Inadequate sanitation is a leading cause of poverty in developing countries, largely because it causes premature mortality. But policymakers in Nigeria still struggle to improve sanitation practices despite their importance to national health and poverty eradication strategies.

IFS and Royal Holloway researchers, in partnership with WaterAid, provide new evidence on the effectiveness of one of the most popular interventions used by policy-makers and NGOs to improve rural sanitation practices in developing countries. The Nigeria study shows that Community-Led Total Sanitation only works in poorer communities and does not cause everyone in the community to adopt safe sanitation practices.

Inadequate sanitation is a leading cause of poverty in developing countries, largely because it causes premature mortality (with an estimated 1,800 child deaths per day due to unsafe water, sanitation and hygiene) and other impacts on health. The UN’s sixth Sustainable Development Goal calls for water and sanitation for all and recognises that safe sanitation practices form a crucial element of future social development and economic prosperity.

Poor sanitation, and in its most extreme form open defecation, is particularly acute in some countries. 76% of those who defecate in the open live in one of seven countries. One of these is Nigeria, the 7th most populous country in the world. In 2015, less than one third of the Nigerian population had access to basic sanitation. More worryingly, access to sanitation has decreased over the last decade.

In November 2018, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari declared a state of emergency on water supply, sanitation, and hygiene. Designing effective sanitation policies is crucial to Nigeria’s national health and poverty eradication strategies.

Sanitation in developing countries - evaluating a national strategy

New research, conducted by researchers at the IFS and Royal Holloway in partnership with WaterAid, evaluates the effectiveness of a Community-Led Total Sanitation intervention in two states of Nigeria. This approach was part of Nigeria’s Strategy for Scaling up Sanitation and Hygiene. It aims to induce communities to eradicate open defecation by providing information and organising community meetings that together aim to trigger a desire for collective behaviour change, encourage communities to construct and use toilets, and encourage innovation and mutual support.

Key lessons for Nigerian national sanitation and health strategies

The key lessons from this work are:

- The Community-Led Total Sanitation effort led to more toilet constructionand use, thereby reducing open defecation, in poorer and more isolated communities.

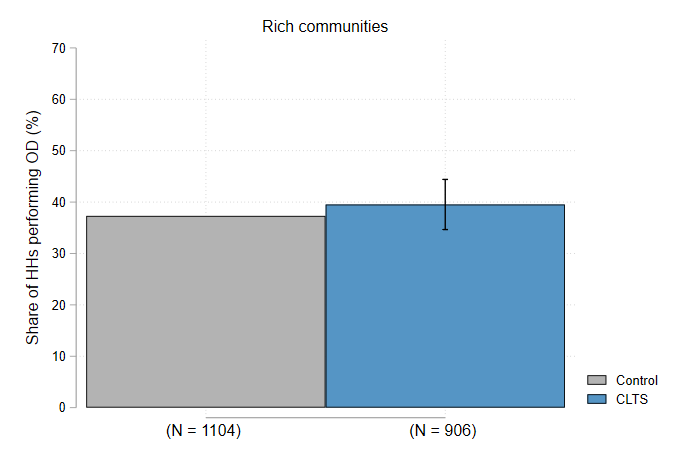

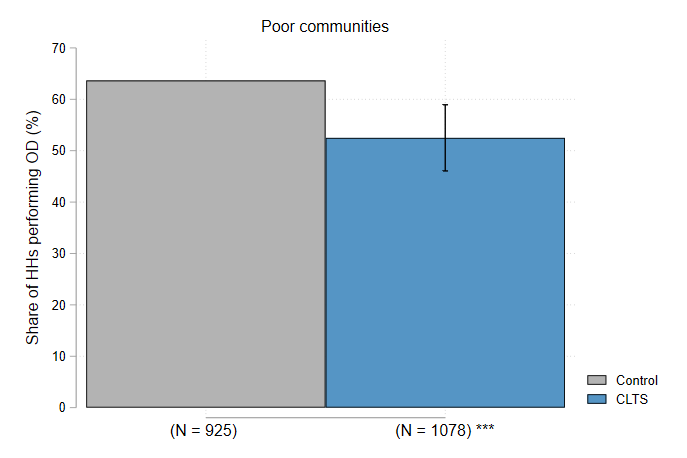

- The prevalence of open defecation declined by an average of nine percentage points in poorer communities, in line with an increase in toilet ownership rates by one third compared to poor areas where CLTS was not implemented. But there was no discernible change in richer communities (see Figure 1). Therefore, to ensure resources are well used, policymakers should consider targetingCLTS towards poor communities.

- Open defecation remains common in both rich and poor areas, and so policymakers should explore alternative sanitation improvement strategies.

These findings will be used by stakeholders, including WaterAid, when advising the Nigerian Government on its national sanitation and health strategies.

Figure 1: Impacts of Community-Led Total Sanitation on Open Defecation

Improving national sanitation strategies in developing countries

Our evaluation of the Nigerian programme implies that resources can be used in a more efficient manner by targeting sanitation programmes at poorer rural areas where they are more likely to be effective.

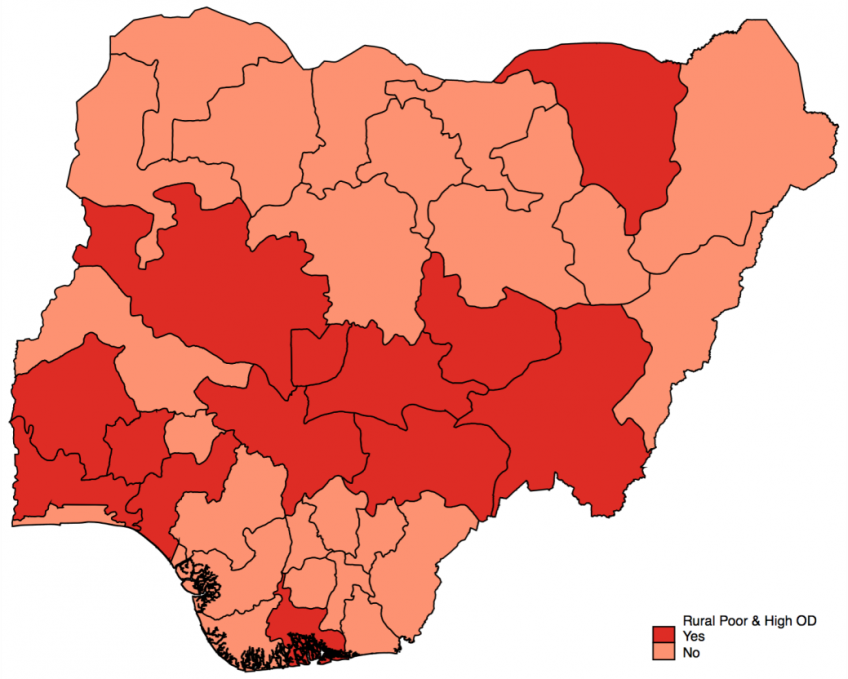

We model this approach in Figure 2. Using data from the 2013 Demographic and Health Survey, we map the Nigerian states where Community-Led Total Sanitation interventions are likely to have the largest impact. Red indicates states most likely to benefit from the programme, with low sanitation coverage and low wealth. This modelling could be done at a lower level of aggregation, even identifying specific settlements and communities where CLTS would be effective.

Figure 2: Strategic targeting of CLTS

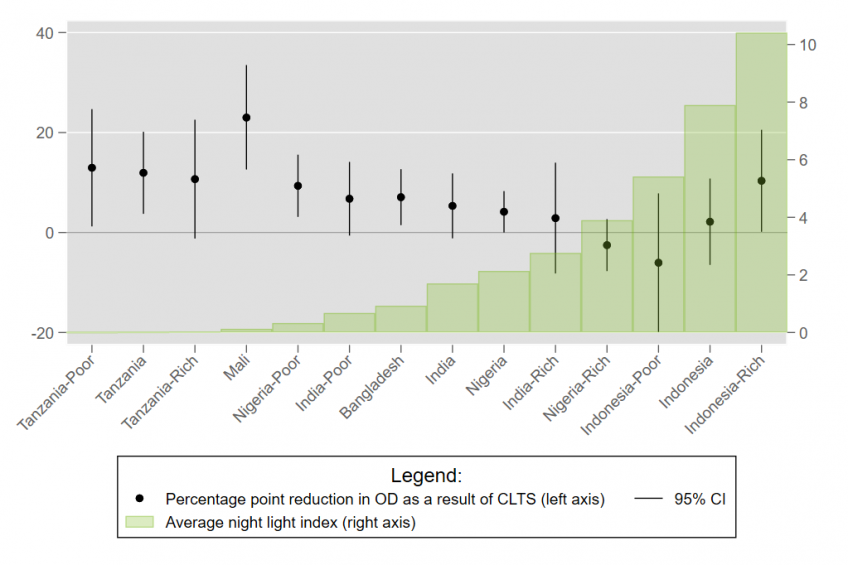

It is likely that targeting would also be effective in other countries. Community-Led Total Sanitation interventions have been implemented in several Latin American, Asian and African countries (shown in Figure 3). Randomised control trials evaluating these programmes in Mali, India, Tanzania, Bangladesh and Indonesia have found widely differing impacts, ranging from a 30 percentage point increase in toilet ownership in Mali to no detectable impacts on toilet ownership in Bangladesh. Yet these countries and study areas have very different levels of wealth. We can use the average intensity of lighting at night as a proxy of the wealth of communities to order existing studies of Community-Led Total Sanitation. This suggests that sanitation interventions have larger impacts in poorer areas, such as Tanzania, and low or no impacts in relatively richer areas, such as Indonesia (See Figure 4). This supports the idea that, given limited resources, targeting poorer areas is going to maximise the impact of Community-Led Total Sanitation.

Figure 3: Countries in which CLTS has been implemented in the past

Figure 4: CLTS impacts on OD and toilet ownership by average study area night light index

Community-Led Total Sanitation programmes have been successful in significantly reducing open defecation in poor communities. But not everyone has access to sanitation, and a large number of people in both poor and rich communities continue to openly defecate. A promising new approach is 'Sanitation Marketing', which targets local businesses and helps them increase the supply of toilets. This approach was shown to significantly increase sanitation coverage in Cambodia. However, even these approaches have proven to be slow to bring about results. Business subsidies or incentives can help encourage private sector activity in this underserved market, and micro-finance options for customers might well be needed. Given that, especially in poor communities, it remains the very poor who do not change their sanitation practices, targeted subsidies could be considered, following a model implemented by the Indian Government. Policymakers will need to keep innovating, testing and evaluating existing and new approaches in order to develop a comprehensive national strategy and adapt solutions that work in one context to different conditions.

Erik Harvey, Programme Support Director at WaterAid, said:

“We began this detailed study with IFS because earlier qualitative research indicated that Community-Led Total Sanitation was not being as effective as was hoped in accelerating sanitation access in Nigeria. That research suggested that CLTS alone was not responding to the aspirational desires of many households for a modern affordable toilet, an option that did not exist in the market. Our more recent work has been trialling support to local businesses to market and sell affordable, modern-looking and easy to purchase toilets. This has demonstrated that market-based solutions might well prove to be an additional sanitation strategy which drives forward progress in Nigeria. However, more work is needed to refine and scale this strategy. Importantly, though, this detailed research indicates that smarter targeting of CLTS investments and effort could be employed, targeting poorer communities where CLTS appears to be more effective and ensuring that the poor are not left behind. This might also improve the cost effectiveness of the wider strategy.”

Dr. Britta Augsburg, Associate Director at IFS and an author of the study, said:

“In 2015, less than one third of the Nigerian population had access to basic sanitation and access has actually decreased over the last decade. Our large Randomised Control Trial in two states of Nigeria assessed the long-term impact of a Community-Led Total Sanitation intervention.

We find that more toilets were built and used, and open defecation reduced, only in poorer and more isolated communities. This implies that policymakers should target interventions at these communities and consider complementary approaches to improve sanitation.”